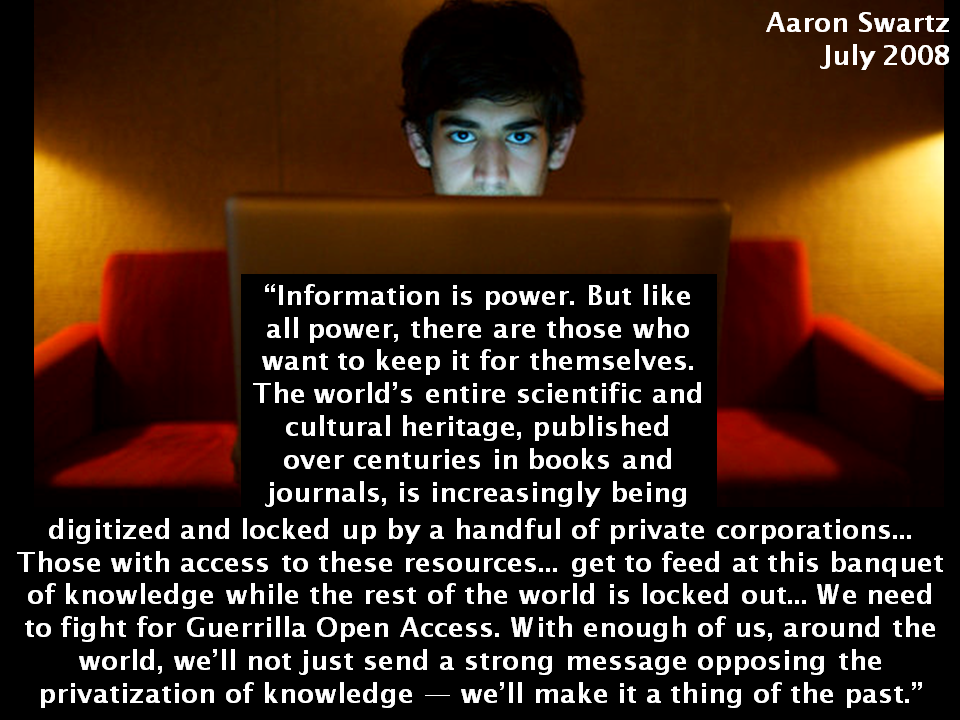

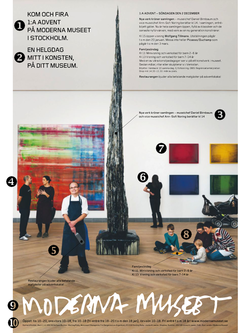

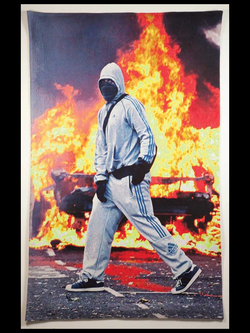

Marc Quinn, The Creation of History (2012)

Marc Quinn, The Creation of History (2012) This single incident gave rise to a spate of riots across England. The worst scenes took place in the capital. A defining image of that summer of violence is a photograph taken by the Turkish born photojournalist, Kerim Okten.

It shows a man in a grey tracksuit and trainers. The skin on his hands is covered by black gloves. His face is veiled by a mask such that only his eyes are visible: they gaze fixedly at the camera lens. Framing that stare are the orange flames and choking black smoke of a burning vehicle.

Various versions of this iconic scene are available online. They differ in all sorts of major and minor ways. Some depict the main protagonist in alternative poses; others show bystanders looking on at the searing shell of the car.

Text invariably accompanies the picture wherever it appears. A front page headline such as “The battle for London” turns this masked celebrity into a capital warrior. Replace that caption with something like “Yob rule” and our battle-scarred warrior becomes a mindless hoodlum. His slow, purposeful steps and cold stare do indeed make this lord of misrule appear above the law.

The rights to Okten’s image have now been acquired by the British artist Marc Quinn. He has used it as the inspiration for a variety of artworks including paintings, a sculpture and even a tapestry. The latter has been entitled The Creation of History (2012) and exists in an edition of five.

The title chose by Quinn reflects his belief that the 2011 riots constitute “a piece of contemporary history”. The artist is quick to add, however, that this history – like every past event – is “a complex story and raises as many questions as it [does] answers. Is this man a politically motivated rioter? A looter? What is in his pocket? And rucksack? More intriguingly, the mask he wears appears to be police-issue: could he even be a policeman?”(1)

The merest suggestion that our photogenic “yob” might in fact be a lawgiver rather than a lawbreaker disturbs this already troubling image, transforming it before our very eyes.

This is exacerbated further in Quinn’s tapestry transmutation. Metamorphosing the pixels of a digital photo into the knots of a woven image catapults this contemporary history back in time. Now our “yob” can stand alongside armour-suited warriors in a medieval pageant.

The rich heritage of Quinn’s The Creation of History makes it worthy to enter into the sacred realm of the museum. And what better institution than Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery? This establishment rose like a phoenix from the flames of a riot: on 10th October 1831 a group of rabble-rousers intent on creating a little history of their own torched the palatial home of the Duke of Newcastle in protest at his opposition to electoral reform.

For fifty years the burnt out shell of the building remained an admonitory reminder of this bad behaviour. Then, in the 1870s, it was converted into the first municipally funded museum outside of London.

This place of learning and leisure still stands. And it only exists thanks to the sort of scenes that were to take place 180 years later – not only in London but also Nottingham, where Canning Circus police station was firebombed by tracksuited warriors / yobs.

So, with this in mind, wouldn’t it make perfect sense for the curators at Nottingham Castle Museum to acquire one of the five editions of Marc Quinn’s The Creation of History? It could hang on the same walls that were once covered by tapestries – before “yob rule” led to them being unceremoniously ripped down and either burnt or “sold to bystanders at three shillings per yard.”(2)

___

Notes

(1) Cited in Gareth Harris, “London riots get tied up in knots”, The Art Newspaper, Iss. 243, 07/02/2013, accessed 08/02/2013 at http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/quinn-tapestry/28545.

(2) Harry Gill, A Short History of Nottingham Castle (1904), available at, http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/gill1904/reformbill.htm.