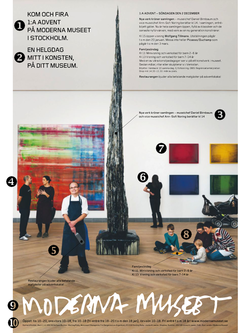

1 Moderna Museet is a place of celebration for all. This is important to stress at the outset because some misguided people continue to insist on treating our museums as either mausoleums or bastions of elitist culture. Moderna Museet isn’t like that. It’s a place to come and have fun; to celebrate things like the start of the Christmas period. And what better way to escape the commercialisation of this sacred event than by going on a pilgrimage to a secular temple of art such as Moderna Museet.

2 Moderna Museet puts you in the picture: when there you will be in the midst of art – your art, your museum (mitt i konsten, på ditt museum).

3 The director and his deputy have given up their holiday to greet the visitors. Tomorrow afternoon – Sunday 2 December – Daniel Birnbaum and Ann-Sofi Noring will talk about their latest acquisitions. In so doing they affirm that Moderna Museet is living up to its reputation: it is filled both with modern Old Masters (fylld av klassiker) and “with the work of a new generation of artists” (med verk av en ny generation konstnärer). These new works, we are told, “crown the collection” (kröner samlingen). They also enable the recently appointed director to put his mark on the museum. This raises lots of fascinating questions: What has the museum acquired under this leader that it might not have under its predecessor? Which criteria are used when choosing what to buy? Who makes the decisions? What did the purchases cost? Who are the donors? Who are the artists? And what personal connections link them with Birnbaum and his colleagues? Will any of these questions be addressed when the director speaks? They certainly should be, after all, this is your museum.

4 Who are these people so deep in conversation? A perfect pair: enthusiastic gesture is met with rapt attention. These two are clearly art lovers. But they aren’t visitors. Nor are they security guards. Instead they are young, trendy invigilators just waiting to share their love of art with the museum’s well-behaved guests. How do we know that they are art lovers? Their gestures and their clothes say it all (see 6).

5 This isn’t an art lover, but he looks nice and friendly. He’s carrying the tool of his trade and wearing his work clothes (just like the couple in 4). But his place of work isn’t the galleries. Nevertheless, rather than being marginalised, this menial worker is given pride of place. Indeed, he looks rather like a work of art: culinary art. Because Moderna Museet isn’t just about consuming art. It’s a place to eat and socialise. That’s why the chef is important enough to be included here. But he isn’t that special. His name is not given. Nor are those of the two invigilators. In fact, only two people are referred to by their names. And neither of them is visible. Standing in as substitutes for the director and his deputy are the artworks that they have sanctified by choosing to include them in the collections of Moderna Museet. The art stands for them. It embodies them. Thus Sterling Ruby’s Monument Stalagmite could be renamed: Monument Birnbaum. It’s a bold assertion of his fitness to lead; his regal good taste (thanks to this and the other acquisitions that “crown the collection”).

6 This person adopts the ideal art pose, with one hand on hip, the other touching the face in a gesture of deep contemplation. She wears the uniform of the art lover, dressed as she is entirely in black. She is part of the same tribe as the invigilators (4) who serve as acolytes assisting at the altar of High Art. This true believer is standing at a respectful distance from the art, not touching but visually consuming. Unfortunately, she is not able to stand directly in front of this particular artwork because there is an object is in the way. But this is not a sculpture; it’s a child’s pushchair! This obstacle is not just there by chance. It’s as symbolic as any of the paintings on the wall. It says: this is an accessible, family-friendly museum in which children are welcome (see 8).

7 The art is shown in glorious isolation in this pristine, white-cubed gallery. This lends it a spurious, “neutral” quality in which nothing comes between us and the art (we are, after all, “mitt i konsten” (1)). There is not a label or interpretation panel in sight. None of the works are literally framed in the sense of there being borders around the paintings or separate plinths under the sculptures. But they are framed in all sorts of other ways. This advertisement and all its messages (overt and subliminal) are frames. Art never speaks for itself, no matter how white and bare the walls.

8 We have already been reassured that the museum is not a mausoleum (1). Now we are reminded that it is not a library either. It’s a playground – for art lovers, young and old. Perhaps this trio of immaculately behaved children will one day be the artists (or museum directors) of the future? With luck they will grow up to wear black clothes and feel as at home in the museum as the lady in 6. The art instructor – just like the proud parent – does her best to make this a reality: she acts as a mediator of the art. She and the other parents and guardians are surrogates of the invigilators seen in 4. During the years 2004-2011 “Zon Moderna” served as the forum for Moderna Museet’s youngest guests. This initiative has been disbanded by the current director. But he is not reducing the museum’s commitment to children. Far from it: they are now brought into the bosom of the museum (mitt i konsten). Zon Moderna ran the risk of being dismissed as a case of “ghettoisation”: “an area specifically reserved for extra activities, and largely containing children within these spaces” (Gillian Thomas, “‘Why are you playing at washing up again?’ Some reasons and methods for developing exhibitions for children” in Roger Miles & Lauro Zavala (eds) Towards the Museum of the Future: New European Perspectives, London and New York: Routledge, 1994, p. 118.) The kids visible in this advertisement are not relegated to some sort of out-of-sight ghetto: we see them as they are just about to scribble away on the floor of the museum, centimetres from the museum’s latest priceless acquisition (5).

9 The museum’s logo adds to the friendly atmosphere: a personal signature which is actually a work of art, based as it is on Robert Rauschenberg’s handwriting. How long will it be before the museum decides to rebrand and ditch this naff typeface?

10 The museum is open every day except Mondays. There is even free entry on extended Friday evenings – perfect for those trendy young things that opt to stay on to drink in the museum’s newest space: a bar. There was a time when Moderna Museet – like all Sweden’s national museums – was free for all: now adults must pay because the current government says so. But the most important visitors still get in for free, namely children up to 18 years old. With luck, by the time they reach maturity they will have blossomed into the sorts of adults seen in this advertisement. They will thus be willing to pay to enter the museum and reacquaint themselves the fresh acquisitions that are to be introduced tomorrow: these are the works that today’s children will grow up with and later recognise as canonical works in their own personal museums of art. This recognition and sense of ownership will help ease the awkward truth that, by charging its citizens to enter Sweden’s Moderna Museet, they will actually be paying twice. After all, their high taxes have already paid for the museum. Their museum.