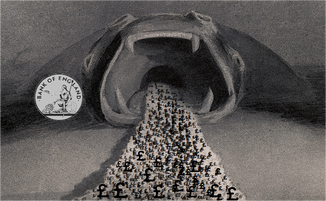

Quantitative Easing (after Alfred Kubin) The Bank of England is very, very fond of money. Its insatiable love for lucre has led it on a hell-bent mission to churn out the stuff in colossal quantities. This is known quaintly as “quantitative easing”. Fortunately, the super intelligent electronic age in which we live means that the Bank of England doesn’t need to print money like it did in ye olden times. These days a simple press of a button is all it takes to magic it up. And we are talking big magic. An estimated £375bn – and counting.(1) Meanwhile, bankers get bonuses for failure. HSBC has been implicated in drug running and money laundering. And those clever boys at Barclays Bank have been diligently manipulating the LIBOR rate. Oh, and don’t forget the ever-increasing and ever-more costly efforts being made to save the Euro. For a long time I struggled and failed to comprehend this will-o’-the-wisp economics. Now, however, it all makes perfect sense. You see, the mistake I made was to think that I was living in a town called Nottingham in the middle of England. Whereas in reality I am a resident of the Dream Realm in a city known as Pearl. One thing above all others characterises this place: it's an all-pervading fraudulence. This condition is so pervasive that it is easily overlooked. To the casual glance, buying and bargaining go on here according to the same customs as everywhere. This, however, is mere pretence, a grotesque sham. The whole of the money economy is “symbolic”. You never know how much you have. Money comes and goes, is handed out and taken in: everyone practices a certain amount of sleight of hand and quickly picks up a few neat ploys. The trick is to sound plausible. You only have to pretend to be handing something over. Here fantasies are simply reality. The incredible thing is the way the same illusion appears in several minds at once. People talk themselves into believing the things they imagined. Everything required to understand the likes of Bob Diamond, Barclays Bank, the Bank of England and the LIBOR-rate rigging scandal is contained in that one paragraph. The words are not mine: they are taken from Alfred Kubin’s The Other Side (Die Andere Seite). The Austrian expressionist artist wrote this mind-blowing novel in 1909. Little did he know that, over a century later, it would help me come to terms with an early 21st century financial crisis. I am re-reading the book in conjunction with Nottingham Contemporary’s exhibition of early works by Kubin. The show opens on Saturday 21st July. I can’t wait to see it. The staff at Nottingham Contemporary have rather unwisely asked me to lead a guided tour through the exhibition at 1 o’clock on Wednesday 1st August.(3) What on earth will I talk about? Thankfully – in contrast to our financial services – a “strong hand” dictates all that occurs in the Dream Realm. So I certainly shouldn’t be lacking Kubinesque inspiration... ____ Notes (1) “Q&A: Quantitative easing”, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-15198789. (2) Alfred Kubin, The Other Side, transl. Mike Mitchell (Sawtry: Dedalus, 2000). The modified quotations reproduced here are taken from pages 60 and 62. (3) “Wednesday Walk Throughs”, http://www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/event/wednesday-walk-throughs-4.  Andy Murray + Wimbledon + nationalism Could there possibly be a more depressing combination? I very much doubt it. Alas, the media’s obsession with all this old balls made it harder to avoid than Christmas. Fortunately on this occasion there is cause for genuine interest and, indeed, celebration. This is because the local foreigner’s loss was Oxfam’s gain. When a gentleman by the name of Nick Newlife died in 2009 he generously bequeathed his entire estate to the charity. This included a betting slip. Back in 2003, Newlife wagered £1,520 that the Swiss tennis player, Roger Federer would win Wimbledon seven times before the year 2019. At odds of 66/1, Oxfam will now collect Newlife’s winnings: a cool £101,840. So, just for once, can we please forget about new balls and old nationalisms? Let's sing the praises of Newlife instead.  Until recently I have lived my little life in only two dimensions. All that changed on Tuesday 3rd July. Because on that evening – and very much against my better instincts – a Siren persuaded me to pay a small fortune for a pair of cheap plastic spectacles. Despite resembling sunglasses these eyepieces afforded no protection against ultraviolet light. They were, however, effective at creating a spurious sense of depth when watching 3D movies at the cinema. The effect they produce is similar to that experienced when looking at Soviet realist portraits of Stalin. All too often Uncle Joe looks like an overlaid cut-out that could at any moment topple out of the frame. A reviled monster of a slightly different kind featured in the film that I settled down to watch. The creature in question had been brought back to life thanks to another siren song, this time broadcast across vast tracts of the cosmos. This call succeeded in luring a rag-bag band of unsuspecting space travellers into its slithery embrace for the purpose of injecting a little fire into their bellies. Hence the title of the film: Prometheus. Ridley Scott’s blockbuster revives and reprises a creature that was first introduced to movie-goers way back in 1979. This was Alien, one of the masterpieces of cinematic history. For its part, Prometheus must count as one of the disasterpieces of the silver screen – whether it be in two dimensions or three. Luckily for me, the saving grace of Prometheus was the fact that it happened to be the first (and I suspect last) time that I opted to pay for an extra dimension. Fittingly enough, this 3D experience turned it into an expensive novelty. Alien was visually stunning, excellently written and well acted with a plausible (albeit fantastic) plot that remains to this day thought provoking, gripping and genuinely scary. Moreover, it was underpinned by an excoriating social commentary on the machinations of big business. The omninational Weylan-Yutani corporation’s casual disregard for its human employees contrasted with the genuine interest and sympathy they generate in us, the audience. Prometheus is the absolute antithesis of all this. Its plot merits no comment whatsoever. And yet, bizarrely enough, the fact that it is so utterly awful renders it the perfect prequel to Alien. A specially-made pair of 3D spectacles should be hastily manufactured and given to Ridley Scott’s extraterrestrial creation. I have a feeling that its razor sharp mouth would hang open in gob-smacked admiration for its master’s work. This is because Prometheus is the ultimate parasite. It owes its existence entirely due to its host. Without that host – i.e. the original film – it would be nothing. Alien’s prequel is a mind-numbingly naked commercial venture that treats the paying public with the same contempt as the Weylan-Yutani company showed to the doomed crew of the spaceship, Nostromo. One member of that crew is the character, Kane – played so brilliantly by John Hurt. In a particularly memorable scene we see him in a prone position, his features occluded by the facehugging Alien. The best way to sum up Prometheus is to look upon Kane as an embodiment of the 1979 film as a whole. Thanks to the prequel it is now no longer possible to properly appreciate that movie. This is because, enfolding it in a deathly embrace and leeching it of all its vital signs, is its bastard spawn: Prometheus. The unearthly star of Alien would surely applaud this act of ruthless parasitism. But s/he would, I feel, have one criticism. The name is all wrong. The single word title beginning with “P” should not be Prometheus but Parasitoid: a parasite that kills its host. Because that’s exactly what Prometheus does to Alien.  “Phallic verticality, which has a long history but which at present is becoming more prevalent, cries out for explanation.” So wrote Henri Lefebvre in his 1974 work, The Production of Space.(1) Nowhere in the whole of Europe is phallic verticality more evident today than in the heart of central London. I am, of course, referring to The Shard, which has just been unsheathed. Renzo Piano’s erection is obscene in the sense of being “ridiculously or offensively high”.(2) That same word – obscene – is also used by Lefebvre. Thoughts of phallic verticality prompted Lefebvre to reflect on “the general fact that walls, enclosures and façades serve to define both a scene (where something takes place) and an obscene area to which everything that cannot or may not happen on the scene is relegated”(3). When it comes to The Shard, the scene was set by a dazzling “spectacle”, namely an inaugural laser show.(4) Now consider this: if The Shard is the scene, does this not relegate the rest of London to the obscene? Or is the reverse the case? If so, only in their wildest dreams will the vast majority of Londoners come close to the obscenities that will surely unfold in the “exclusive residences [and] luxury hotel” situated behind The Shard’s glossy 309.6 metre high glass ramparts.(5) Wherever the (ob)scene lies, it is to be hoped that The Shard does not suffer the same fate as J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise. First published in 1975, the starring attraction of Ballard’s polemical novel is a “vertical township”. This mutates into a “huge animate presence” in the lives of its tragically privileged residents. They become dog-eating captives of “a malevolent zoo”, the geometry of which goads them into ever more barbaric acts of degradation.(6) By the end of Ballard’s book the scene is bare. Only the obscene remains. So, fellow citizens of the obscene, please do bear all this in mind before deciding to pay the sky-high sums of money necessary to take a fleeting ride up to The Shard’s viewing gallery.(7) Take my advice: stick to the obscenities of our everyday world – and let Renzo and his phalanx of phallic fetishists go shaft themselves. ____ Notes (1) Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, Oxford & Malden, Blackwell, 1974, p.36. (2) “Obscene”, adj., Oxford English Dictionary, http://oed.com/view/Entry/129823. (3) As note 1. (4) “London’s Shard skyscraper celebrated with laser show”, BBC News, 05/07/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-18716658. (5) “The Shard, Europe's tallest building, unveiled in London”, The Guardian, 05/07/2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2012/jul/05/the-shard-unveiled-london). (6) J.G. Ballard, High-Rise, London, Jonathan Cape, 1975. (7) As note 4. |

Para, jämsides med.

En annan sort. Dénis Lindbohm, Bevingaren, 1980: 90 Even a parasite like me should be permitted to feed at the banquet of knowledge

I once posted comments as Bevingaren at guardian.co.uk

Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

_

Note All parasitoids are parasites, but not all parasites are parasitoids Parasitoid "A parasite that always ultimately destroys its host" (Oxford English Dictionary) I live off you

And you live off me And the whole world Lives off everybody See we gotta be exploited By somebody, by somebody, by somebody X-Ray Spex <I live off you> Germ Free Adolescents 1978 From symbiosis

to parasitism is a short step. The word is now a virus. William Burroughs

<operation rewrite> |

key words: architecture | archive | art | commemoration | design | ethics | framing | freedom of speech | heritage | heroes and villains | history | illicit trade | landscape | media | memorial | memory | museum | music | nordic | nottingham trent university | parasite | politics | science fiction | shockmolt | statue | stuart burch | tourism | words |