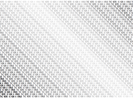

I have been disrupted twice in the last couple of days. On both occasions the disruption has been presented to me as positively welcome – something to celebrate. The first disturbance arose during a talk about MOOCs. This acronym stands for massive online open courses. Their proponents claim these to be the-next-big-thing in education. Old fashioned universities beware: soon they’ll be superseded by entirely online providers charging a fraction of the price and servicing hundreds of thousands of participants drawn from the four corners of the globe. This is all thanks to disruptive technologies: IT innovations that disturb the status quo as surely as music downloads have annihilated the high-street record store. Be that as it may, listening to a gorgeously slick gentleman from a posh US university preaching about disruption made me suspicious. Don’t be lulled into thinking that this particular brand of commotion is inherently exciting, radical or open. Because that would be to belie the imperialistic ambitions of many of the organisations that lurk beneath the mantle of disruptive technology. The next day also proved to be cheerfully disruptive. On this occasion the challenge to the natural order occurred towards the close of a highly civilized seminar hosted by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. Representatives of groups funded by the AHRC’s various knowledge exchange schemes were invited to meet in Bristol and share ideas. One participant happened to mention how her scheme had helped facilitate “disruptive thinking”. This in turn got me thinking disruptively. To what extent do funders tolerate such behaviour? Moreover, “disruptive thinking” is promoted because it can lead to failure. But it would take a bold person to declare in an end-of-project-report that their research was brilliantly abortive, that they didn’t bother doing what they had promised and had in fact consciously subverted the aims of the funding organisation: all in the name of disruptive thinking. Would such disruptions be welcome? Would they lead to renewed investment from a grateful funding body? Bear in mind that these sources of money must also be accountable to a board of trustees, some government department or the largess of a tax avoiding business. I pondered these things whilst making my way to Bristol Temple Meads to catch my train back to snowy Nottingham. Suddenly I looked up and – to my surprise – found myself in the midst of a ferocious riot. Sword-wielding soldiers on horseback were pitching into a crowd of angry protestors. Such was the ferocity of this incident that I was mighty pleased to have turned up after it had started. Precisely 182 years after.  The incident in question was taking place in a large mural painted on the backdrop to a patch of rough ground adjacent to the Bath Road. It commemorates the Reform Bill riots that took place in Bristol’s Queen Square in 1831. This disturbance has a resonance in the city to which I was headed. In Nottingham similar acts of insurrection also took place in 1831. On 10th October a crowd of residents, frustrated by the lack of progress towards electoral reform, gathered in Market Square before heading up the hill to the site of the old Nottingham castle, then the home of the dukes of Newcastle. They burnt the mansion to the ground. It stayed that way for fifty years until the gutted shell was transformed into a municipal museum and art gallery. The fullness of time has turned the disruptive events of 1831 into local histories. They are also part of a neat linear story of political change leading to universal suffrage. But would the imperfect democracy enjoyed by Britons today have been achieved if some individuals weren’t prepared to disrupt the present order? And wouldn’t it be ironic if these disruptive deeds were to one day become the subject matter of some not-for-profit (sic) MOOC or even a British knowledge exchange initiative? Goodness, what a disruptive thought! The third one this week!  Marc Quinn, The Creation of History (2012) Marc Quinn, The Creation of History (2012) On Thursday 4th August 2011 officers of the Metropolitan Police Service stopped a taxi on Ferry Lane in Tottenham Hale, London. Its occupant – Mark Duggan – was subsequently shot dead in uncertain circumstances. This single incident gave rise to a spate of riots across England. The worst scenes took place in the capital. A defining image of that summer of violence is a photograph taken by the Turkish born photojournalist, Kerim Okten. It shows a man in a grey tracksuit and trainers. The skin on his hands is covered by black gloves. His face is veiled by a mask such that only his eyes are visible: they gaze fixedly at the camera lens. Framing that stare are the orange flames and choking black smoke of a burning vehicle. Various versions of this iconic scene are available online. They differ in all sorts of major and minor ways. Some depict the main protagonist in alternative poses; others show bystanders looking on at the searing shell of the car. Text invariably accompanies the picture wherever it appears. A front page headline such as “The battle for London” turns this masked celebrity into a capital warrior. Replace that caption with something like “Yob rule” and our battle-scarred warrior becomes a mindless hoodlum. His slow, purposeful steps and cold stare do indeed make this lord of misrule appear above the law. The rights to Okten’s image have now been acquired by the British artist Marc Quinn. He has used it as the inspiration for a variety of artworks including paintings, a sculpture and even a tapestry. The latter has been entitled The Creation of History (2012) and exists in an edition of five. The title chose by Quinn reflects his belief that the 2011 riots constitute “a piece of contemporary history”. The artist is quick to add, however, that this history – like every past event – is “a complex story and raises as many questions as it [does] answers. Is this man a politically motivated rioter? A looter? What is in his pocket? And rucksack? More intriguingly, the mask he wears appears to be police-issue: could he even be a policeman?”(1) The merest suggestion that our photogenic “yob” might in fact be a lawgiver rather than a lawbreaker disturbs this already troubling image, transforming it before our very eyes. This is exacerbated further in Quinn’s tapestry transmutation. Metamorphosing the pixels of a digital photo into the knots of a woven image catapults this contemporary history back in time. Now our “yob” can stand alongside armour-suited warriors in a medieval pageant. The rich heritage of Quinn’s The Creation of History makes it worthy to enter into the sacred realm of the museum. And what better institution than Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery? This establishment rose like a phoenix from the flames of a riot: on 10th October 1831 a group of rabble-rousers intent on creating a little history of their own torched the palatial home of the Duke of Newcastle in protest at his opposition to electoral reform. For fifty years the burnt out shell of the building remained an admonitory reminder of this bad behaviour. Then, in the 1870s, it was converted into the first municipally funded museum outside of London. This place of learning and leisure still stands. And it only exists thanks to the sort of scenes that were to take place 180 years later – not only in London but also Nottingham, where Canning Circus police station was firebombed by tracksuited warriors / yobs. So, with this in mind, wouldn’t it make perfect sense for the curators at Nottingham Castle Museum to acquire one of the five editions of Marc Quinn’s The Creation of History? It could hang on the same walls that were once covered by tapestries – before “yob rule” led to them being unceremoniously ripped down and either burnt or “sold to bystanders at three shillings per yard.”(2) ___ Notes (1) Cited in Gareth Harris, “London riots get tied up in knots”, The Art Newspaper, Iss. 243, 07/02/2013, accessed 08/02/2013 at http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/quinn-tapestry/28545. (2) Harry Gill, A Short History of Nottingham Castle (1904), available at, http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/gill1904/reformbill.htm._  Yesterday afternoon was spent wandering aimlessly around Nottingham city centre. On the way to nowhere I stopped off at Nottingham Contemporary where two new exhibitions have just opened. Not really in the mood for art, I devoted most time to looking at all the tiny trinkets on sale in the shop. Trendy, totally superfluous treasures were mixed in with the art publications and designer tat. Exiting briefly into the sunshine I promptly plunged into a very different world: that of the Broadmarsh Shopping Centre. Hurrying past the serried ranks of empty retail units I descended into the bowels of the earth. Reaching the end of the escalator I glanced momentarily at the entrance to the so-called “City of Caves”. This place always makes me chuckle: I am supposed to have a professional interest in museums and heritage. Nevertheless, in the decade that I’ve spent living in Nottingham I have not once entered this tourist-attraction-that-time-forgot. Moving on I glimpsed another sad sight: Gordon Scott. This shoe shop has been in the Broadmarsh Shopping Centre ever since the monstrous mall opened in the early 1970s. Now all that’s left are a few pairs of sale items and a couple of extraordinarily bored-looking staff waiting to be made properly redundant. Even more depressing is the disappearance of the mechanical monkey from the shop window. His loopy tricks on the horizontal bar were, for me, the centre’s absolute high point. He was the retail world equivalent of Wollaton Hall’s George the gorilla.

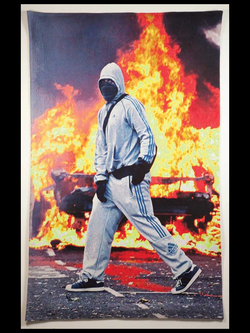

These textual “traffic signals” had a dual purpose. Firstly, of course, they signified the Riddler. This is not the first time that this cartoon villain has featured in Newling’s art: a precedent was Between (Even the Riddler Makes Wishes), an installation from 1996 commissioned and hosted by Nottingham’s Broadway Cinema and Arts Centre. Yesterday at the Broadmarsh Centre the Riddler’s question marks had an additional function. Passersby were stopped and asked to identify something that they valued. In return they were given a swatch of the same cloth used to make the Riddler’s jacket. They could then head off into the crowds with this pinned to their chests – generating riddles wherever they went. My smart-arse answer to the question – what do you value? – was respect. Because that’s the quality I appreciate most in people and groups: “the condition or state of being esteemed, honoured, or highly thought of.” If you think about it, the root cause of our society’s ills is the general lack of respect for politicians, big business, organisations and for so many individuals we come into contact with in our daily lives. And how many of us manage to get through life with their self-respect intact? Newling intends to collate the “public values” gathered together at the Broadmarsh Centre and integrate them into a talk to be given as part of his “Ecologies of Value”, on show at Nottingham Contemporary until 7th April. My advice would be to get there as soon as you can – and ideally before the whole of Nottingham city centre goes into liquidation and all that we value goes with it.

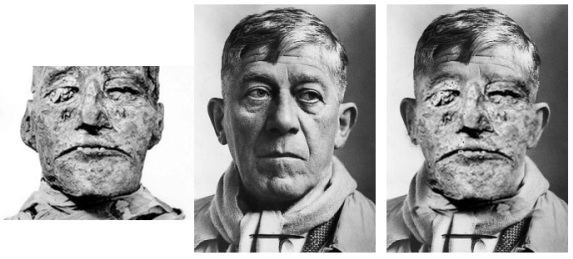

New research seems to confirm what many have long suspected: King Ramesses III was murdered, probably by having his throat cut sometime around the year 1155BC. This is reported by the BBC alongside a small photograph of the king’s mummified visage.(1) He looks strangely familiar... and then it struck me how much he reminds me of the late, great expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka. I wonder if their DNA crossed at some point over the past few millennia?

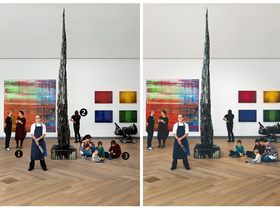

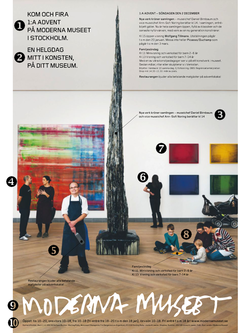

___ Note (1) Michelle Roberts, “King Ramesses III’s throat was slit, analysis reveals”, BBC News, 18/12/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-20755264  Moderna Museet online (left) and in print (right) Earlier this month I reflected on a fascinating newspaper advertisement for Sweden’s Moderna Museet. Additional investigation has now turned this commentary into a spot-the-difference. On the museum’s website is a promotional feature that includes the same image.(i) Only, on closer inspection, it becomes apparent that it differs from the version that appeared in the newspaper, Dagens Nyheter. 1 The invigilator’s clothing has been darkened. This ensures that she wears the attire of the art lover (i.e. dressed entirely in black). The same is true of the trousers worn by the visitor (2). 2 The visitor has been shifted further to the right. In the online image it looks as if she is reading a label next to the work rather than looking at the art itself. This risked introducing a troublesome piece of interpretation – a barrier preventing her from being in the midst of the art (mitt i konsten). This is alleviated by shifting the visitor closer to the art (although not too close given that the all-important pushchair is still in the way). 3 The posture of the hands-on art educator has changed. Her rather motherly pose is replaced by a less overtly protective position in relation to the three children. This prevents her from coming between them and the art (again ensuring that they are mitt i konsten). In the image on the left the children and the facilitator have their back to Sterling Ruby’s Monument Stalagmite. The print version spins them around such that all the group members are oriented towards the sculpture. All this confirms the meticulous attention that has gone into this carefully crafted framing of Moderna Museet. A genuinely artful and art full advertisement. ___ Note (i) “Fira 1:a advent på Moderna Museet”, http://www.modernamuseet.se/sv/Stockholm/Nyheter/2012/Fira-1a-advent-pa-Moderna-Museet/. The image is credited to the photographer, Åsa Lundén.  Today’s issue of the newspaper, Dagens Nyheter features a full-page advertisement for Moderna Museet – Sweden’s national museum of modern and contemporary art. Every art lover knows that a picture is worth a thousand words. So, with this in mind, I’ve picked out ten points of interest and used them to structure a one thousand word reflection on this most artful of advertisements: 1 Moderna Museet is a place of celebration for all. This is important to stress at the outset because some misguided people continue to insist on treating our museums as either mausoleums or bastions of elitist culture. Moderna Museet isn’t like that. It’s a place to come and have fun; to celebrate things like the start of the Christmas period. And what better way to escape the commercialisation of this sacred event than by going on a pilgrimage to a secular temple of art such as Moderna Museet. 2 Moderna Museet puts you in the picture: when there you will be in the midst of art – your art, your museum (mitt i konsten, på ditt museum). 3 The director and his deputy have given up their holiday to greet the visitors. Tomorrow afternoon – Sunday 2 December – Daniel Birnbaum and Ann-Sofi Noring will talk about their latest acquisitions. In so doing they affirm that Moderna Museet is living up to its reputation: it is filled both with modern Old Masters (fylld av klassiker) and “with the work of a new generation of artists” (med verk av en ny generation konstnärer). These new works, we are told, “crown the collection” (kröner samlingen). They also enable the recently appointed director to put his mark on the museum. This raises lots of fascinating questions: What has the museum acquired under this leader that it might not have under its predecessor? Which criteria are used when choosing what to buy? Who makes the decisions? What did the purchases cost? Who are the donors? Who are the artists? And what personal connections link them with Birnbaum and his colleagues? Will any of these questions be addressed when the director speaks? They certainly should be, after all, this is your museum. 4 Who are these people so deep in conversation? A perfect pair: enthusiastic gesture is met with rapt attention. These two are clearly art lovers. But they aren’t visitors. Nor are they security guards. Instead they are young, trendy invigilators just waiting to share their love of art with the museum’s well-behaved guests. How do we know that they are art lovers? Their gestures and their clothes say it all (see 6). 5 This isn’t an art lover, but he looks nice and friendly. He’s carrying the tool of his trade and wearing his work clothes (just like the couple in 4). But his place of work isn’t the galleries. Nevertheless, rather than being marginalised, this menial worker is given pride of place. Indeed, he looks rather like a work of art: culinary art. Because Moderna Museet isn’t just about consuming art. It’s a place to eat and socialise. That’s why the chef is important enough to be included here. But he isn’t that special. His name is not given. Nor are those of the two invigilators. In fact, only two people are referred to by their names. And neither of them is visible. Standing in as substitutes for the director and his deputy are the artworks that they have sanctified by choosing to include them in the collections of Moderna Museet. The art stands for them. It embodies them. Thus Sterling Ruby’s Monument Stalagmite could be renamed: Monument Birnbaum. It’s a bold assertion of his fitness to lead; his regal good taste (thanks to this and the other acquisitions that “crown the collection”). 6 This person adopts the ideal art pose, with one hand on hip, the other touching the face in a gesture of deep contemplation. She wears the uniform of the art lover, dressed as she is entirely in black. She is part of the same tribe as the invigilators (4) who serve as acolytes assisting at the altar of High Art. This true believer is standing at a respectful distance from the art, not touching but visually consuming. Unfortunately, she is not able to stand directly in front of this particular artwork because there is an object is in the way. But this is not a sculpture; it’s a child’s pushchair! This obstacle is not just there by chance. It’s as symbolic as any of the paintings on the wall. It says: this is an accessible, family-friendly museum in which children are welcome (see 8). 7 The art is shown in glorious isolation in this pristine, white-cubed gallery. This lends it a spurious, “neutral” quality in which nothing comes between us and the art (we are, after all, “mitt i konsten” (1)). There is not a label or interpretation panel in sight. None of the works are literally framed in the sense of there being borders around the paintings or separate plinths under the sculptures. But they are framed in all sorts of other ways. This advertisement and all its messages (overt and subliminal) are frames. Art never speaks for itself, no matter how white and bare the walls. 8 We have already been reassured that the museum is not a mausoleum (1). Now we are reminded that it is not a library either. It’s a playground – for art lovers, young and old. Perhaps this trio of immaculately behaved children will one day be the artists (or museum directors) of the future? With luck they will grow up to wear black clothes and feel as at home in the museum as the lady in 6. The art instructor – just like the proud parent – does her best to make this a reality: she acts as a mediator of the art. She and the other parents and guardians are surrogates of the invigilators seen in 4. During the years 2004-2011 “Zon Moderna” served as the forum for Moderna Museet’s youngest guests. This initiative has been disbanded by the current director. But he is not reducing the museum’s commitment to children. Far from it: they are now brought into the bosom of the museum (mitt i konsten). Zon Moderna ran the risk of being dismissed as a case of “ghettoisation”: “an area specifically reserved for extra activities, and largely containing children within these spaces” (Gillian Thomas, “‘Why are you playing at washing up again?’ Some reasons and methods for developing exhibitions for children” in Roger Miles & Lauro Zavala (eds) Towards the Museum of the Future: New European Perspectives, London and New York: Routledge, 1994, p. 118.) The kids visible in this advertisement are not relegated to some sort of out-of-sight ghetto: we see them as they are just about to scribble away on the floor of the museum, centimetres from the museum’s latest priceless acquisition (5). 9 The museum’s logo adds to the friendly atmosphere: a personal signature which is actually a work of art, based as it is on Robert Rauschenberg’s handwriting. How long will it be before the museum decides to rebrand and ditch this naff typeface? 10 The museum is open every day except Mondays. There is even free entry on extended Friday evenings – perfect for those trendy young things that opt to stay on to drink in the museum’s newest space: a bar. There was a time when Moderna Museet – like all Sweden’s national museums – was free for all: now adults must pay because the current government says so. But the most important visitors still get in for free, namely children up to 18 years old. With luck, by the time they reach maturity they will have blossomed into the sorts of adults seen in this advertisement. They will thus be willing to pay to enter the museum and reacquaint themselves the fresh acquisitions that are to be introduced tomorrow: these are the works that today’s children will grow up with and later recognise as canonical works in their own personal museums of art. This recognition and sense of ownership will help ease the awkward truth that, by charging its citizens to enter Sweden’s Moderna Museet, they will actually be paying twice. After all, their high taxes have already paid for the museum. Their museum.  Pauline Oliveros, 1968-9 (with modifications) “Why wasn’t a poet sent to the moon? What if Starwars’ Robot R2-D2 were able to scan the world’s arts for their strengths and weaknesses, making available its output after scanning to aid artists in their search for new aesthetic solutions. What if Starwars translator C-3PO could make translations for audiences in their bewilderment with new forms, translation from one kind of artist to another, or become go-between for scientists, technologists and artists? Would it help? Would it be of redeeming social value? “The side effects of technology, such as the pollution of our planet and the danger of ultimate destruction, are not solved. Technology breeds the need for more technology which breeds more side effects in a self-perpetuating binge. “The foresight required for the solutions needed must come not only from the deepest of scientific thought, but also from the deepest of artistic thought. The artistic side of the scientist as well as the scientific side of the artist must continually be cultivated. The artistic scientist and the scientific artist have suffered subjugation by those who have sought power and control at the expense of human and aesthetic values.” Pauline Oliveros, Software for People: Collected Writings 1963-80, Baltimore: Smith Publications, 1984, p. 176  On Sunday 11 November a fascinating debate took place at Arkitekturmuseet (Sweden’s national museum of architecture). It marked the culmination of a weekend of activities to celebrate the institution’s fiftieth anniversary. Events included guided tours of the Rafael Moneo-designed building which Arkitekturmuseet shares with another of Sweden’s state museums, namely Moderna Museet. The highlight of the festivities focused on the commemorative publication, The Swedish Museum of Architecture: A Fifty Year Perspective. This was launched following a series of reflections by two contributors to the book, Thordis Arrhenius and Bengt O.H. Johansson (the latter was director of the museum from 1966-77). This was followed by a panel debate entitled “Midlife crisis or stroppy teenager? A discussion about Arkitekturmuseet yesterday, today, tomorrow”.(1) It was at this point that matters started to get interesting. It quickly became apparent that the past, present and future of Arkitekturmuseet are far from settled. Much attention was given to the recently expanded role of the museum. This is summed up in an introductory section of the anniversary book. Under the rubric, “More than a museum”, Monica Fundin Pourshahidi cites a press release by the Swedish minister of culture, Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth in which it is stated that, from 2009 onwards, Arkitekturmuseet is vested with being a “power centre” not only for architecture but also for design: “The Museum of Architecture can and must be a display window and a distinct voice in the debate on social planning, architecture, design and sustainable development”.(2) This point was taken up by Arkitekturmuseet’s present director, Lena Rahoult. But her positive spin was immediately problematised by a fellow panel member, the architectural historian Martin Rörby. The focus of his criticisms was a recent governmental memorandum which instructed the institution to engage in “promotion and communication” (främjande och kommunikation) rather than “traditional museum activities” (traditionell museiverksamhet). This would be best signalled by a change in title, with the word “museum” being replaced by “centre” or “arena”.(3) Rörby expressed reservations about such a shift in focus, fearing that an increase in breadth would come at the expense of depth and critical engagement. He was also troubled by the vague, empty rhetoric of the memorandum. On the other hand, the notion of going beyond what was expected of a “traditional” museum was nothing new. Rörby illustrated this point by citing Arkitekturmuseet’s past involvement in the often heated debate regarding Sergels torg in central Stockholm. He stressed the rapidity of the museum’s response which enabled it to react to a pressing, contemporary issue. This active engagement, however, was only possible because of the museum’s unrivalled collections of artefacts, architectural models and other archival documents. Rörby was of the opinion that the museum would find it far harder – if not impossible – to arrange such an exhibition in the additional field of design. This is because the museum responsible for the national design collection is another entirely separate institution, namely Nationalmuseum. The design holdings will remain there, despite Arkitekturmuseet’s increased mandate. In the light of this one can be forgiven for questioning the basis for adding design to the museum of architecture. The oddness of this situation was beautifully demonstrated by the fact that, at the very same time that this debate was unfolding at Arkitekturmuseet, Nationalmuseum just down the road was holding a “theme day” on “handicraft, time and creativity” in association with its craft and design exhibition, Slow Art.(4) Way back in the late 1980s and early 1990s the museum fraternity in Sweden dreamed of a museum of industrial design (Konstindustrimuseet) being housed in Tullhuset adjacent to the main Nationalmuseum building in the Blasieholmen area of Stockholm. This nineteenth century toll house was to have been expanded to allow for 5000 square metres of exhibition space. Alas, this imaginative idea proved abortive, as did a plan to deploy the spectacular Amiralitetshuset on the island of Skeppsholmen.(5) In the wake of these failed initiatives comes the current half-baked decision to place the design burden on the ill-equipped museum of architecture. Meanwhile, in February 2013, Nationalmuseum will close for a period of four years during which time a multi-million kronor refurbishment will take place. This, one would have thought, would be the ideal opportunity to resolve the status of design in Sweden. The risk is that the investment in Nationalmuseum is being made against a contested, confused and contradictory context. Exacerbating this frankly farcical state of affairs is the added complication of Arkitekturmuseet’s relationship with Moderna Museet. These two museums, as has been noted, share a building. One might therefore have thought that it would sensible for the pair to unite, especially given the enlarged remit of Arkitekturmuseet. Indeed, in 1998 it was proposed that modern design dating from 1900 onwards should be moved to Moderna Museet.(6) On being asked about the relationship with her neighbour, Arkitekturmuseet’s director Lena Rahoult made a few platitudinous comments and paid compliments to Daniel Birnbaum, her counterpart at Moderna Museet. However, when it comes to Moderna Museet’s upcoming exhibition on Le Corbusier, it emerged that the museum of architecture will not be involved.(7) This, it strikes me, represents a potentially serious threat to the autonomy of Arkitekturmuseet. If the Le Corbusier exhibition is a success despite (or perhaps because of) the exclusion of Arkitekturmuseet, then the argument is being made that Moderna Museet is more than capable of taking over this field. Daniel Birnbaum would no doubt be delighted. He is a very shrewd operator. Upon taking over the running of Moderna Museet he erased all trace of its former director in the most charming manner: by turning the whole museum over to photography. This had a number of consequences. It facilitated a tabula rasa whilst showing Birnbaum to be both innovative and in step with the history of the museum. This in turn stifled any potential suggestion that photography was not being accorded sufficient attention. This was a smart move given that the formerly separate museum of photography had been subsumed into the collections of Moderna Museet on the completion of Rafael Moneo’s building in 1998. With this potential criticism snuffed out, Birnbaum then set about curtailing the independence of the museum’s satellite institution, Moderna Museet Malmö. This was led by Magnus Jensner until a “restructuring” made his position untenable and prompted his resignation.(8) In March of this year Jensner was succeeded by Birnbaum’s man in Stockholm, John Peter Nilsson. Against the background of these strategic manoeuvres the decision to mount an exhibition on Le Corbusier at Moderna Museet is no mere innocent happenstance. It can be interpreted as part of a calculated empire building process. And, if the recent debate at Arkitekturmuseet is anything to go by, Birnbaum is a giant among pygmies on the Swedish cultural scene. Perhaps mindful of this, at the same time as spouting her platitudes, Lena Rahoult has been busy mounting the barricades. She has taken the decision to withdraw Arkitekturmuseet from the bookstore that it has shared with Moderna Museet since the inception of Moneo’s building. All the books are being sold at a reduction of 60% whilst magazines and postcards are being flogged off for a few kronor. Once this stock has been disposed, Arkitekturmuseet will open a separate retail establishment in its own part of the locale. This development is notable given that the bookstore was one of the very few aspects of the building where the two institutions merged. Another is the shared ticket desk. Moneo designed the building to incorporate the old drill-hall where Moderna Museet began life and which is now occupied by Arkitekturmuseet. In so doing he provided a new entrance and closed the original doorway. Rahoult plans to reopen this entrance whilst keeping the other in use. Birnbaum is on record as describing this proposal as “ludicrous” (befängd).(9) Well he might, because one of the main criticisms of Moneo’s building is its very modest and hard-to-find entrance. Should Arkitekturmuseet prove to be the main gateway into the combined museum it may well increase the number of visitors to the architecture collection, but it will draw attention from what is currently the dominant partner, Moderna Museet. The proposed changes to the shop and entrance have led to claims that Arkitekturmuseet wishes to “break free from Moderna Museet”.(10) The paradoxical situation has therefore arisen whereby, at the same time that Arkitekturmuseet struggles to work across disciplines in one direction, it is placing barriers to the museum next door. There is, of course, no reason why different disciplines should not be brought together in a single museum. A case in point is the Museum of Modern Art, MOMA. Its mission statement is grounded in the belief [t]hat modern and contemporary art transcend national boundaries and involve all forms of visual expression, including painting and sculpture, drawings, prints and illustrated books, photography, architecture and design, and film and video, as well as new forms yet to be developed or understood, that reflect and explore the artistic issues of the era.(11) Another example closer to home is Norway. However, in this case the forced union of art, architecture and design has been far from amicable or straightforward. But at least Norway’s National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design is being given a grand new building in which to unite. This is not the case in Sweden. No one should be surprised about this given the paltry cultural policies of the present alliance government under the stewardship of its mediocre minister of culture, Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth. When it came to the festivities to mark Arkitekturmuseet’s jubilee debate, the icing on the birthday cake occurred when the panel turned to the audience for questions and response. Up stepped Jöran Lindvall. He remains – as he was at pains to make clear – the longest serving director of Arkitekturmuseet (during the years 1985-1999). Nevertheless, he added pointedly, no one had thought to ask him to contribute to the fiftieth anniversary publication. His absence from its pages was a timely reminder that such official records are as partial as they are political. That much is shown by a similar publication released to mark Moderna Museet’s own fiftieth anniversary in 2008. Such historical tomes might seem to be rooted in the past, but their main aim is to seek to placate the politicised present whilst simultaneously shaping the uncertain future. As if to underline this, Jöran Lindvall presented the current holder of the post he once occupied with a bag stuffed full of newspaper cuttings and other documents from his private collection relating to exhibitions that took place during his time at the museum. He declared his willingness to donate these to Arkitekturmuseet, but on one condition: that it remain a museum devoted to architecture. Lena Rahoult accepted this generous offer. She could hardly do otherwise. It will be interesting to follow the fate of Lindvall’s loaded gift. Indeed, all those involved in museums would do well to keep track of events in Sweden and watch with interest as commentators, practitioners, museum professionals and politicians plot their next moves in a battle that is more comedy than tragedy. But that is not to say that the outcome is likely to leave very many people laughing. _____ Notes (1) The panel participants were the director of Arkitekturmuseet, Lena Rahoult together with Fredrik Kjellgren (architect), Petrus Palmér (designer), Birgitta Ramdell (director of Form/Design centre, Malmö) and the architectural historian Martin Rörby (Skönhetsrådet). The chair was Kristina Hultman. (2) Press release dated 19 December 2008, cited in Main Zimm (ed.) The Swedish Museum of Architecture: A Fifty Year Perspective, Stockholm: Arkitekturmuseet, p. 4. (3) Cited in “Stora förändringar föreslås på Arkitekturmuseet”, Arkitektur, undated, http://www.arkitektur.se/stora-forandringar-foreslas-pa-arkitekturmuseet (accessed 12/11/2012). (4) Slow Art, Nationalmuseum, 10 May 2012 – 3 February 2013. The special event that took place on Sunday 11 November included a talk by Cilla Robach (“Slow Art – om hantverk, tid och kreativitet”) followed by a craft activity for children (see the advertisement on p. 7 of the Kultur section of that day’s issue of the newspaper, Dagens Nyheter). (5) Mikael Ahlund (ed.) Konst kräver rum. Nationalmuseums historia och framtid, Nationalmusei skriftserie 17, 2002, pp. 76-77. (6) Ahlund, 2002, p. 77. (7) Moderna Museet’s exhibition has been given the name “Moment – Le Corbusier’s Secret Laboratory” and will run from 19 January – 28 April 2013. The decision not to collaborate with Arkitekturmuseet is ironic given that the latter put together the exhibition “Le Corbusier and Stockholm” in 1987. (8) “Magnus Jensner slutar i Malmö”, Expressen, 20/10/2012, http://www.expressen.se/kvp/magnus-jensner-slutar-i-malmo. (9) “Arkitekturmuseets femtioårskris – en intervju”, Arkitektur, undated, http://www.arkitektur.se/arkitekturmuseets-femtioarskris-en-intervju (accessed 12/11/2012). (10) Hanna Weiderud, “Arkitekturmuseet bryter sig loss från Moderna”, SVT, 01/11/2012, http://www.svt.se/nyheter/regionalt/abc/arkitekturmuseet-bryter-sig-loss-fran-moderna. (11) Collections Management Policy, The Museum of Modern Art, available at, http://www.moma.org/docs/explore/CollectionsMgmtPolicyMoMA_Oct10.pdf. “Without knowing it, I was crossing the rainbow bridge from reality to dream.”

L. P. Hartley, The Go-between, 1953, vii, p. 77  Yesterday a group of people gathered in Custom House Square, Belfast. They then opened three large freezers, removed 1,517 diminutive frozen figures and began placing them around the square. When the task was complete they stood back and spent the next twenty minutes watching as these human icicles melted before their eyes. This happening was part of a festival to mark the centenary of the sinking of the RMS Titanic. The person responsible for this particular commemorative response was the Brazilian born artist, Néle Azevedo (born 1950). Her poignant idea was entitled, Minimum Monument. It was intended as a celebration of the “ephemeral and diminutive, as opposed to what is monumental and grandiose.”(1) For instances of the “monumental and grandiose” one might turn to John Blackwood’s book London’s Immortals: The complete commemorative outdoor statues (Savoy Press, 1989). The cover features an individual who exudes monumentality and grandiosity. This is all the more remarkable given that the person being represented is physically frail – so weak in fact that he requires a walking stick to support his gargantuan frame. But his greatness comes from the courage of his convictions rather than the strength of his sinews. The bronze effigy commemorates a man who is seemingly so famous that he requires no elaborate inscription. On the pedestal on which he is placed is but a single word: Churchill. Statues of this nature are intended to create the illusion of universal acclaim and permanence. This façade came crashing down during my investigations into this sculpture and the other commemorative monuments that surround the Houses of Parliament in London. In the year 2000 a riot broke out where the natural order was inverted: protestors mounted Churchill’s plinth and daubed it with graffiti. In the process they turned the war hero into a bloated warmonger. For a short time this establishment figure became a punk icon (courtesy of the grass mohican draped over his pate).(2) I wonder what the late, great playwright and author, Dennis Potter would have made of such bad behaviour? I ask because, way back in 1967 in one of his earliest plays for television, Potter took a “swipe at Churchillianism”.(3) Alas, the original recordings of this and two other such works were subsequently deleted by the BBC. Years later Potter reflected on his vanished play. He dismissed it as “polemical” and “overtly political”, something with which now felt uncomfortable.(4) We are not in a position to judge if he was right to be so self-critical given that the work no longer exists. This makes the title of the play deeply ironic. It was called, Message for Posterity. That phrase sums up Ivor Roberts Jones’s titanic statue of Churchill that has scowled at parliament ever since its inauguration in 1973. But messages for posterity do not always have to be like this. They can be more modest and far less bombastic – like Néle Azevedo’s already vanished tribute to the 1,517 lives cut short when the monumental and grandiose prow of the Titanic sank beneath the icy waves of the North Atlantic Ocean. ____ Notes (1) Nuala McCann, “Poignant ice tribute to Titanic victims”, BBC News, 21/10/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-20020498 (2) For more about this, see my doctoral thesis, On Stage at the Theatre of State: The Monuments and Memorials in Parliament Square, London (A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, March 2003). (3) Graham Fuller (ed.), Potter on Potter, London, Faber and Faber, 1993, p. 17. (4) Potter on Potter, pp. 31-32.  The British Museum possesses many thousands of fascinating objects. One of its self-styled “highlights” is a rather plain looking marble inscription. It comes from Rome and is dated around AD 193-211. What makes it so interesting are the things it does not show. These include the names of two relatives of the Roman emperor, Septimius Severus (AD 145-211), namely his daughter-in-law Plautilla and his son Geta. The latter was murdered by Septimius Severus’ other son Caracalla. He was Plautilla’s husband and Geta’s brother. The two siblings were bitter rivals following the death of their father. It is believed that Caracalla murdered Geta and then had his treacherous and much despised wife executed. And, to make matters even worse, they were then subjected to the posthumous punishment of damnatio memoriae: their names were expunged from all official records and inscriptions and their statues and all images of them were destroyed. This process [damnatio memoriae] was the most horrendous fate a Roman could suffer, as it removed him from the memory of society.(1) However, removing Geta from public consciousness was not a straightforward matter. Caracalla was obliged to give his brother a proper funeral and burial due to Geta’s popularity both with the Roman army and among substantial sections of Roman society. This explains why the names of Geta and Plautilla were included on the British Museum’s marble inscription, only to be scratched out later on. Why am I mentioning all this? Because a modern-day form of damnatio memoriae is currently unfolding in British society. This is in relation to the disc jockey, children’s television presenter and media celebrity, Sir Jimmy Savile OBE, KCSG, LLD (1926-2011). When he died last year at the ripe old age of 84 he was hailed a loveable hero who had done much for charity. Now, however, revelations have come to light suggesting that he was, in the words of the police, a “predatory sex offender”.(2) As a result, strenuous efforts are being made to expunge him from the public record.(3) Thus, the charity that bears his name is considering a rebrand. A plaque attached to his former home in Scarborough was vandalised and has since been removed. So too has the sign denoting “Savile’s View” in the same town. Meanwhile, in Leeds, his name has been deleted from a list of great achievers at the Civic Hall. A statue in Glasgow has been taken down in an act of officially sanctioned iconoclasm. The same fate has been dished out to the elaborate headstone marking Savile’s grave. This last-named act of damnatio memoriae is in some ways a pity given the unintended poignancy of the epitaph inscribed on the stone: “It Was Good While It Lasted”. It was almost as if Savile knew that he would one day have to atone for his evil deeds. Atonement has, alas, come too late for those that suffered at the hands of Savile. To make matters worse, his considerable fame has been replaced by a burgeoning notoriety. This is reminiscent of the damnatio memoriae that befell Geta and his sister-in-law Plautilla. The marble inscription that once carried their name is a “highlight” of the British Museum precisely because of the dark deeds associated with them and the futile efforts made to delete them from history. In their case, damnatio memoriae has, in a perverse way, enhanced their posthumous status centuries after their grisly deaths. Let’s hope that the same will not be said of the late Jimmy Savile – an individual who has gone from saint to scoundrel in the space of just a few short months. ___ Notes (1) “Marble inscription with damnatio memoriae of Geta, son of Septimius Severus” (Roman, AD 193-211, from Rome, Italy, height 81.5 cm, width 47.5 cm, British Museum, Townley Collection, GR 1805.7-3.210, http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/gr/m/marble_inscription.aspx). (2) Martin Beckford, “Sir Jimmy Savile was a ‘predatory sex offender’, police say”, The Daily Telegraph, 09/10/2012, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/9597158/Sir-Jimmy-Savile-was-a-predatory-sex-offender-police-say.html. (3) “Jimmy Savile’s headstone removed from Scarborough cemetery” and “Sir Jimmy Savile Scarborough footpath sign removed”, BBC News, 12/10 & 08/10/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-19893373 and www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-19867893.  A forgotten painting by the little-known American artist, Mark Rothko has been rediscovered at a London museum. Experts had previously considered Tate Modern’s “Yellow on Moron” to have been executed by the Polish master, Wlodzimierz Umaniec (spelt Vladimir Umanets). However, a novel technique known as a vandal-spectrometry has enabled scientists to detect traces of crudely applied oil paint beneath Umanets’ trademark scrawl. This has prompted art historians to rename the work “Black on Maroon” and determine that it is part of Rothko’s abortive Seagram murals. Inevitably, this reattribution has reduced the value of the piece. It has, however, increased interest in genuine works by Vladimir Umanets. This towering modern-day genius has been likened to the bastard spawn of Marcel Duchamp and Cy Twombly.

Going over to "the other side" is a risky business.

But it sometimes pays off... Alfred Kubin (1877-1959) “The Other Side” Nottingham Contemporary 21st July - 30th September 2012 _  Jamtli is a regional museum in the city of Östersund in central Sweden. In recent days it has been blessed with a great deal of attention. At first this delighted its director, Henrik Zipsane. “All publicity is good publicity” he declared in a newspaper interview last week.(1) Zipsane must have been cursing those words as he announced the cancellation of Jamtli’s exhibition “Udda och jämt” (Odd and even). This was to have been a group show of contemporary Swedish art. Included in the line-up was Lars Vilks. He made a name for himself in 2007 with the publication of his drawings of the prophet Muhammad as a dog-shaped piece of street furniture. This triggered a furious and at times very violent reaction in both Sweden and abroad. Vilks is now obliged to live under police protection and has become synonymous with the polarised views pertaining to religion and freedom of expression. Whatever one’s opinion of Vilks, it is impossible to accuse him of hiding his views on such matters. This is confirmed by his much-publicised decision to travel to New York this month in order to take part in a conference entitled SION (Stop Islamization of Nations). Nevertheless, it seems to have been this specific action that led Jamtli’s leadership to change their mind about including Vilks in “Udda och jämt”. Yet they clearly failed to think through the potential consequences of this move. One by one the other artists in the show announced their decision to withdraw. Eventually it became clear that not enough participants remained and so the exhibition, which was due to open on 30th September, has now been cancelled. This incident touches on lots of highly sensitive issues and gives rise to a host of often strongly held opinions. Oddly enough it is this that appears to be the greatest problem. Earlier this morning a spokesperson for Jamtli appeared on Sweden’s national radio. She lamented that the debate that had arisen threatened to overshadow the art. If this is such a bad thing, why extend an initiation to a so-called conceptual artist like Lars Vilks in the first place? Could it be that Jamtli hoped that Vilks’ presence might have added a touch of spice to the mix – a little of that “good publicity” so craved by Zipsane? If so, this has all gone horribly wrong. Or has it? “Udda och jämt” promises to be one of the most talked about shows in Jamtli’s history – whether it takes place or not. So why don’t its asinine leaders go ahead with the exhibition as arranged? The plans are no doubt well advanced; the text panels and labels for each artwork must be ready to be go. These could be mounted on the wall alongside works by those artists who still wish to participate. Meanwhile, large tracts of white space would indicate those works that have been censored by the institution or self-censored by the artists. Each (non)participant plus other interested commentators could be invited along to the opening. They could enter into debate over what has occurred, why and with what consequences. Each of the artists selected to take part in “Udda och jämt” would be compelled to explain their decisions. Did they withdraw in protest against the museum’s censorship, in support of Lars Vilks or for some other reason? One such protagonist is the painter, Karin Mamma Andersson. She is on record as criticising Jamtli’s belated and apparently arbitrary decision to ban Vilks. But, prior to that, she was presumably happy for one of her paintings to share a wall with a work by Vilks? Or was she unaware of his participation? Whichever was the case, what “Udda och jämt” reveals is the multivocality of artworks and the powerplays inherent in the artworld. Art and artists are constantly being reframed – by the media and by curators in museums. Art never “speaks for itself”. This has been confirmed by the Jamtli debacle. Yet, rather than capitalise on this rare opportunity to unpick the workings of the artworld, what does the museum do? Simply shuts its doors, withdraws from the fray and waits for normal service to resume. The greatest losers here are Jamtli’s public. Because if Jamtli’s leadership had the courage of their convictions and gone ahead with this non-show then something fascinating would have occurred: the audience itself would have taken centre stage. Regular museum-goers and first-time visitors alike could have voiced their opinions about this so-called public institution. Do they applaud or abhor the actions of the museum and the behaviour of the artists? The resulting dialogue would provide a roadmap for future decisions and contribute to an opening-up – a democratisation – of the museum. As it is, by cancelling “Udda och jämt” the likes of Henrik Zipsane have simply placed an embargo on proper debate. And it is this lack of informed discussion and argument that characterises the hysteria around religion and freedom of expression. The only winners here are those people who delight in spreading discord and miscommunication plus those misguided individuals and organisations who insist on separating “art” from life. ___ Note (1) “Jamtli ställer in utställning”, Svenska Dagbladet, 29/08/2012, http://www.svd.se/kultur/jamtli-staller-in-utstallning_7458194.svd. After writing Manipulating Moderna Museet, I decided to revisit the museum for one last look at "Image over Image" – a temporary exhibition devoted to the work of Elaine Sturtevant. This decision was in itself noteworthy. In one of the gallery spaces it’s possible to watch a video of “The Powerful Pull of Simulacra”. This is the title of the lecture Sturtevant gave in conjunction with the show.(1) In it she argues that “objects are out; image is the power”. But if this is the case, why do we need a museum of objects such as Moderna Museet? Indeed, what is the point of making a physical pilgrimage to see “Image over Image”? The answer, I think, is all to do with “the powerful pull of simulacra”. I paid a repeat visit to “Image over Image” in order to savour being in the presence of what might be termed “genuine fakes”. This is a reference to one of the most striking moments of Sturtevant’s lecture: the part when she talks about “falsity presented as truth”. That evocative phrase – “falsity presented as truth” – encapsulates “Image over Image”.  My moment of epiphany came as I genuflected in a room containing four works entitled Warhol Flowers. These are all dated 1990 – the same year of creation as those Brillo boxes that Pontus Hultén so very generously donated to Moderna Museet. And then it struck me! Moderna Museet is a secular temple. Its sacred spaces and canonical texts authenticate that which it displays. Sturtevant’s “Image over Image” has allowed Moderna Museet to reclaim Pontus Hultén’s “fake” Brillo boxes. This in turn expunges their questionable provenance which threatened to besmirch the good name of Moderna Museet’s most illustrious leader. Thanks to Sturtevant, it is now possible for the Brillo boxes’ falsity to be presented as truth. For is it not the case that, at the very same time that Sturtevant was propagating Warhol Flowers, Hultén was conjuring up a whole new suite of Brillo boxes? Endorsing the former has the effect of validating the latter. And that’s how dead artist’s can produce genuine works of art long after their deaths. If you still don’t get it, well, that’s probably just your “determination to be stupid” – to quote that true original, Elaine Sturtevant.(2) ___ Note (1) Elaine Sturtevant, “The Powerful Pull of Simulacra”, a talk given at the symposium, Beyond Cynicism: Political Forms of Opposition, Protest, and Provocation in Art, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 18th March 2012. (2) Ibid.  clone, copy, counterfeit, duplicate, fabrication, facsimile, fake, forgery, imitation, impersonation, impression, likeness, mock-up, paraphrase, parody, replica, reproduction, ringer, simulacrum, transcription, xerox Each of the words listed above mean roughly the same thing. Yet they are distinguised by subtle nuances, each of which leads to crucial differences in import. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the word synonym as: two or more words (in the same language) having the same general sense, but possessing each of them meanings which are not shared by the other or others, or having different shades of meaning or implications appropriate to different contexts. The notion that meaning and implication are context dependent is highly significant. Take, for example, the following scenarios: a) A forgery on sale for millions of pounds at an auction b) a study hanging on the wall of an art gallery The first of these two examples indicates a deliberate (often criminal) attempt to pass one thing off as another in order to undermine the art world and/or swindle both the potential buyer and the auction house. A “study”, however, is an entirely different class of object: An artistic production executed for the sake of acquiring skill or knowledge, or to serve as a preparation for future work; a careful preliminary sketch for a work of art, or (more usually) for some detail or portion of it; an artist’s pictorial record of his observation of some object, incident, or effect, or of something that occurs to his mind, intended for his own guidance in his subsequent work. The intention of the creator and the characterisation of the object determine in large part whether something is a worthless “forgery” or a valuable “study”.  The fascinating implications of all this have been apparent to people visiting Moderna Museet's “Image over Image” (17/03 – 26/08/2012). At first glance this temporary exhibition looks like an impressive assemblage of iconic pieces by the likes of Joseph Beuys, Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol. However, the person responsible for these works (and a few sex toys besides) is in fact the American artist, Elaine Sturtevant (born 1930). A leaflet accompanying the show revels in this assemblage of playfully deceptive things that “defies description and instead frustrates, provokes and gathers strength in maintaining a perpetual stance of opposition.” This characterisation is exactly the sort of on-the-edge radicalism to which Moderna Museet aspires. The Sturtevant show provides the institution with an opportunity to demonstrate that “Moderna Museet also has a history of confronting authenticity”. Cited in this regard are “the now internationally infamous Brillo boxes.” The museum leaflet does not go into detail about why they are so infamous. Nor does it point out that they are currently exhibited in a gallery space immediately after the Sturtevant exhibition. The boxes in question are piled up in a corner alongside a label that reads: Here, Moderna Museet emphatically does not deploy the Sturtevant exhibition to “confront” questions of authenticity or explore the nuances of words such as fabrication, facsimile, fake, forgery... Instead it lulls the vast majority of visitors into believing that the pile of boxes in the corner is a genuine artwork by Andy Warhol – produced three years after his death. In truth these items were donated to Moderna Museet by their creator: its former director, Pontus Hultén. He used this institutional endorsement as leverage when selling other such boxes to private collectors at enormous personal profit.(1) None of this is mentioned. Visitors are instead fed the normal fare of artspeak mystification enfolding both the temporary Sturtevant exhibition and the museum’s permanent collection. Of the latter, one room is themed: “Art as idea, language and process”. An introductory text panel by Cecilia Widenheim explains how the likes of “Marcel Broodthaers and Hans Haacke were among the first to criticise the art museum as an institution.” At the same time an artist such as “Öyvind Fahlström encouraged his viewers to ‘manipulate’ language.” A superb example of language manipulation and the continuing need to critique an institution such as Moderna Museet lies immediately behind this vapid statement, namely those Brillo boxes by Andy Warhol (sic). The means to highlight this are simple. All it would take is an action entirely in the spirit of Sturtevant’s “perpetual stance of opposition” and Moderna Museet’s proud “history of confronting authenticity” and Öyvind Fahlström’s encouragement for “viewers to ‘manipulate’ language.” All one need do is quietly remove the “manipulative” label next to that pile of Brillo boxes and replace it with the following – what shall we call it? – facsimile, imitation, likeness, parody, transcription: ___

Note (1) See my chapter “Introducing Mr Moderna Museet: Pontus Hultén and Sweden’s Museum of Modern Art” in Kate Hill (ed.) Museums and Biographies: Stories, Objects, Identities (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2012), pp. 29-44. ___ For a follow up to this story, see Falsity presented as truth (22/08/2012).  There has been a spate of scare stories recently about the "threat" to "our" heritage. These often centre on fabulously valuable artworks owned by extremely wealthy people. Occasionally the objects in question have been hanging quietly on the wall of a public art gallery - until, that is, the owner dies or runs out of cash. A case in point is Picasso's Child with a Dove (1901). This is currently in limbo. It has been sold secretively to an unknown foreign buyer for an undisclosed sum (thought to be in the region of £50m).(1) Unfortunately, the new owner will have to wait a while before getting their hands on it. This is because Britain's minister of culture has placed a temporary ban on its export in the hope that sufficient money can be raised to "save" this item "for the nation". This is exactly what occurred just the other day in relation to a painting by Manet.(2) It cost the Ashmolean Museum £7.83m to "save" this integral piece of British culture from the rapacious hands of a dastardly foreigner. But don't believe this rhetoric. Oh, and ignore the headline price and touching tales of little street urchins parting with their pennies to rescue this relic. It took upwards of £20m in tax breaks and donations from public bodies to ensure that national pride remained intact. Yet this doesn't bode well for Picasso's little bird-loving child, does it? The art fund (sic) must surely have run out by now. So too have the superlatives and dramatic warnings from our media luvvies and museum moguls. Indeed, their fighting funds were already seriously depleted after they chose to place £95m in the hands of the Duke of Sutherland - one of the richest men in the country.(3) This act of Robin Hood in reverse stopped the robber baron from flogging two paintings by Titian along with other trinkets he and his family had so generously loaned to the National Galleries of Scotland. And now the same museum is coming under "threat" again! Soon we will have to watch as Picasso's little bird migrates to sunnier climes. The national heritage will be fatally winged by this terrible loss. The consequences just don't bear thinking about... This is just as well because, in truth, the only repercussions will be a slight dent to national pride plus a small gap on a museum wall. This can be filled by any number of artworks that are currently in store at the National Galleries of Scotland. Deathly quiet will then return to this mausoleum of art... Until, that is, we are panicked by the next siren call as yet another integral piece of Britain's (ha!) much-loved heritage comes under covetous foreign eyes. Tell the world. Tell this to everyone, wherever they are. Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies. 'Cos you never know, you might just see a sweet bird by Picasso fly by... ____ Notes (1) Anon, "Picasso's Child With A Dove in temporary export bar", BBC News, 17/08/12, http://www.bbc.co.uk./news/entertainment-arts-19283696; Maev Kennedy, "Picasso painting Child with a Dove barred from export", The Guardian, 17/08/12, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/aug/17/picasso-child-with-a-dove-painting. (2) Stuart Burch, "Manet money", 08/08/2012, http://www.stuartburch.com/1/post/2012/08/manet-money.html. (3) Stuart Burch, "Purloined for the nation", 03/04/12, http://www.stuartburch.com/1/post/2012/04/purloined-for-the-nation.html. Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus by the French artist Édouard Manet (1832-83) has just been purchased for £7.83. This is far less than the sum that would have been achieved on the open market. The reason for this is because the British government refused to allow the painting to be sold to a foreign buyer.

Once-upon-a-time export bars were justified on the grounds of ensuring that a work of art was being "saved for the nation". Interestingly, the new owner of the portrait - the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford - has rephrased this dubious claim. Manet's work, we are assured, has been "saved for the public". The museum is obviously keen to justify the expenditure on this portrait of a foreign person by a foreign artist. The purchase will, we are told, "completely transform" the Ashmolean, helping to turn it into "a world-leading centre for the study of Impressionist and post Impressionist art." Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus is, in other words, a commodity used as a means of competing with rival collections, both in the UK and abroad. However, the Ashmolean is only able to take part in the competition because this particular item of trade has not been allowed to reach its true "value". This is due to the fact that "aesthetic importance" and national pride are deemed, in this instance, to outweigh considerations of mere money. The result being that the Ashmolean was able to purchase the item in question for only 27% of its market value. The artwork's worth on the open market "net of VAT" was £28,350,000. The enormous difference between this and the £7.83m paid by the Ashmolean represents a huge loss in taxation - at a time when Britain's economy is in a parlous state and when the government (it claims) is doing its utmost to tackle tax avoidance. Mindful of this, the Ashmolean seeks to reassure us that it is "planning a full programme of educational activities, family workshops, and public events inspired by the painting." But consider for a moment how many "educational activities" could be implemented for, say, £20 million (the difference between the "true" value of the artwork and the sum paid by the Ashmolean). Fortunately we don't need to worry about this because money is very rarely talked about in our hallowed museums. Manet's Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus is destined to merge seamlessly into the Ashmolean collection and be toured around various temporary exhibitions. A little label will list the charitable organisations and anonymous givers responsible for "saving it for the public". Yet the true cost of the commodity will be omitted. Manet's money should not, however, be ignored. Nor should one further, pressing issue. Just because Manet's painting is now "publicly" owned does not necessarily mean it will never again become a financial commodity. Alterations to the Museums Association's code of ethics mean that public museums in the UK are now able to "ethically" sell objects from their collections, albeit in exceptional circumstances. This means that the same inventive logic and sleight of hand deployed to acquire Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus could be equally used to justify its future sale. As long, of course, that the money raised can be shown to be "for the benefit of the museum’s collection." Where, however, will all this end? Might the change to the code of ethics be the first step towards the situation in the United States? San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, for example, recently sold Bridle Path by the American artist, Edward Hopper in order to "benefit acquisitions." Perhaps one day the Ashmolean could do the same with the support of the Museums Association and the connivance of the British government? The museum would go on to make a tidy profit from its Manet - some of which could then be used to support future "educational activities". And so it goes on... Money might well be a taboo subject in museums. But the issues raised by Édouard Manet's Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus should serve to remind us that museums have their own carefully constructed economy: one that is just as inventive and artful as the "real" economy with its clever strategies of quantitative easing dreamt up by bands of unethical bankers. With this in mind, should the Ashmolean have been allowed to buy the painting under such circumstances? The answer, I think, is no. Instead, the British government should take a leaf out of the Museums Association's code of ethics. It ought to have allowed the export, on the condition that all monies raised in taxation from the sale were ring-fenced and used to fund "educational activities" in our museums. This would go some way to offsetting recent reductions in museum funding - with outreach and education programmes suffering disproportionately as a consequence. This outcome would be far more ethical and more effective than the spurious tokenism used by the Ashmolean to disguise its glee at acquiring a work of art that only a fraction of the public will see or have any interest in. ___________ Supplemental 09/08/2012 "Donations help keep Manet in UK". So reads the title of an article about this matter in today's Financial Times.(1) The newspaper chooses to foreground the generosity of "1,048 people who donated sums which ranged from £1.50 to £10,000". Framing the story in this manner is a carefully considered ploy. It seeks to underline the sense of universal public support and popular approval for this deal. These contributions are certainly laudable. But they pale into insignificance given that the bulk of the £7.83m came from "the Heritage Lottery Fund, which contributed £5.9m, and the Art Fund, which gave £850,000". The support of these official bodies plus the above-mentioned loss in tax revenue mean that the Ashmolean's latest acquisition must indeed have cost the state at least £20m. This is, indeed, a conservative estimate. It is reported that 80% of the painting's value would have been levied in tax had it been sold on the open market.(2) It is the case, therefore, that the seller not only avoided a large tax bill; he or she also accrued more money by selling it to a UK museum for less than £8m as opposed to securing over £28m from a foreign buyer. So, in a way, the FT is right: a very large donation has indeed kept Manet in the UK. ____ Notes (1) Hannah Kuchler, "Donations help keep Manet in UK", Financial Times, 09/08/2012, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/4168b256-e174-11e1-92f5-00144feab49a.html. (2) Maev Kennedy, "Ashmolean buys Manet's Mademoiselle Claus after raising £7.8m", The Guardian, 08/08/2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/culture/2012/aug/08/ashmolean-buys-manet-mademoiselle-claus. _____________ Other references Anon (2011) "Culture Minister defers export of stunning portrait by Edouard Manet", Department for Culture, Media and Sport, 120/11, 08/12, http://www.culture.gov.uk/news/media_releases/8686.aspx Anon (c.2011) "Last chance to keep Manet’s Portrait of Mademoiselle Claus in the UK", Department for Culture, Media and Sport, undated, accessed 08/09/2012 at, http://www.culture.gov.uk/news/news_stories/8685.aspx Anon (c.2012) "Manet portrait saved for the public", undated, accessed 08/09/2012 at, http://www.ashmolean.org/manet/portrait/ Atkinson, Rebecca (2012) "Ashmolean acquires threatened Manet portrait for £7.83m", Museums Association, 08/08, http://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/08082012-ashmolean-purchases-manet-portrait Burch, Stuart (2012a) "Biting the hand that feeds", 22/03, http://www.stuartburch.com/1/post/2012/03/biting-the-hand-that-feeds.html Burch, Stuart (2012b) "I scream, you scream, we all scream for The Scream", 20/03, http://www.stuartburch.com/1/post/2012/04/i-scream-you-scream-we-all-scream-for-the-scream.html Burch, Stuart (2012c) "A Pearl of Dream Realm economics", 16/07, http://www.stuartburch.com/1/post/2012/07/a-pearl-of-dream-realm-economics.html Holmes, Charlotte (n.d.) "Sale of collections", Museums Association, accessed 08/09/2012 at, http://www.museumsassociation.org/collections/sale-of-collections  Last Friday this particular feline was lucky enough to see Patti Smith in concert. The 65-year old rocker spelled out what was on her mind: Free Pussy, that's what. The well-behaved Swedish audience didn't strike me as being particularly militant. Nevertheless, Patti's riotous behaviour was clearly much appreciated. I had a quick look amongst the cats in the crowd, but didn't manage to spot if Mr Igor S. Neverov was in attendance. If so, he would surely have been purring with pleasure at Patti's perfidious pussy pronouncement...  Quantitative Easing (after Alfred Kubin) The Bank of England is very, very fond of money. Its insatiable love for lucre has led it on a hell-bent mission to churn out the stuff in colossal quantities. This is known quaintly as “quantitative easing”. Fortunately, the super intelligent electronic age in which we live means that the Bank of England doesn’t need to print money like it did in ye olden times. These days a simple press of a button is all it takes to magic it up. And we are talking big magic. An estimated £375bn – and counting.(1) Meanwhile, bankers get bonuses for failure. HSBC has been implicated in drug running and money laundering. And those clever boys at Barclays Bank have been diligently manipulating the LIBOR rate. Oh, and don’t forget the ever-increasing and ever-more costly efforts being made to save the Euro. For a long time I struggled and failed to comprehend this will-o’-the-wisp economics. Now, however, it all makes perfect sense. You see, the mistake I made was to think that I was living in a town called Nottingham in the middle of England. Whereas in reality I am a resident of the Dream Realm in a city known as Pearl. One thing above all others characterises this place: it's an all-pervading fraudulence. This condition is so pervasive that it is easily overlooked. To the casual glance, buying and bargaining go on here according to the same customs as everywhere. This, however, is mere pretence, a grotesque sham. The whole of the money economy is “symbolic”. You never know how much you have. Money comes and goes, is handed out and taken in: everyone practices a certain amount of sleight of hand and quickly picks up a few neat ploys. The trick is to sound plausible. You only have to pretend to be handing something over. Here fantasies are simply reality. The incredible thing is the way the same illusion appears in several minds at once. People talk themselves into believing the things they imagined. Everything required to understand the likes of Bob Diamond, Barclays Bank, the Bank of England and the LIBOR-rate rigging scandal is contained in that one paragraph. The words are not mine: they are taken from Alfred Kubin’s The Other Side (Die Andere Seite). The Austrian expressionist artist wrote this mind-blowing novel in 1909. Little did he know that, over a century later, it would help me come to terms with an early 21st century financial crisis. I am re-reading the book in conjunction with Nottingham Contemporary’s exhibition of early works by Kubin. The show opens on Saturday 21st July. I can’t wait to see it. The staff at Nottingham Contemporary have rather unwisely asked me to lead a guided tour through the exhibition at 1 o’clock on Wednesday 1st August.(3) What on earth will I talk about? Thankfully – in contrast to our financial services – a “strong hand” dictates all that occurs in the Dream Realm. So I certainly shouldn’t be lacking Kubinesque inspiration... ____ Notes (1) “Q&A: Quantitative easing”, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-15198789. (2) Alfred Kubin, The Other Side, transl. Mike Mitchell (Sawtry: Dedalus, 2000). The modified quotations reproduced here are taken from pages 60 and 62. (3) “Wednesday Walk Throughs”, http://www.nottinghamcontemporary.org/event/wednesday-walk-throughs-4. Images to accompany my recent exhibition review of Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery in the county of Kent (Museums Journal, Issue 112 (05), pp. 54-57).

The museum is rightly grateful to that most capacious of collectors, Julius Brenchley (1816-73). This hoarder has been mentioned in an earlier blog posting, which also alluded to the bedroom antics of Maidstone Museum’s former curator, William Lightfoot. See “Brenchley's bedroom benefaction”.  “[A] rich mixture of foreign influences has entered our homes for centuries and continues to do so today.” So says the introductory panel to the exhibition “At Home With the World”. This is the title of the Geffrye Museum’s contribution to the laughably labelled “Cultural Olympiad”. The temporary display seeks to explore notions of Englishness in the domestic sphere. What – if anything – is nationally distinct about the homes of England given the ongoing patterns of “foreign influence” that pervade our public and private spaces? This question resonates with a line of dialogue from a play that I am going to see later this evening just up the road from the Geffrye Museum: “All I want is the England I used to know... When you knew where you were and all the houses had gardens and old ladies could feel safe in the street at night.” This understandable nostalgia is ratcheted into a gleefully xenophobic rant by a mild mannered man who goes by the name of Martin Taylor. He must surely be the most compelling and controversial character conjured up by the playwright, Dennis Potter. His play, Brimstone and Treacle charts how monstrous Martin wheedles his way into the moribund home of the Bates family. Tensions between the unhappily married Mr and Mrs Bates are exacerbated by the condition of their tragic daughter, Pattie. She lays bedridden and brain damaged following a traffic accident. Martin decides to quite literally lend a hand. The nature of his grotesque physical intervention led to the censorship of Potter’s Brimstone and Treacle. Potter wrote his television play for the BBC some four decades ago. Time, however, has not diminished the shocking denouement of the drama. So it is with a growing sense of guilty excitement that I sit in the sun-drenched café of the Geffrye Museum writing these words and waiting impatiently for the drama to unfold. Until now I have only ever seen Potter’s work through the mollifying medium of television. The chance to come within touching distance of Dennis’ devilishly disturbing world has brought me to London and the Arcola Theatre in Hackney. As luck would have it, the last leg of my journey to the theatre involved the number 149 double-decker bus from London Bridge station. It strikes me that the loathsome Norwegian terrorist, Anders Behring Breivik should be compelled to serve out his life sentence on this bus route. He’d be driven out of his miniscule mind by the glorious microcosm of London life that is played out by a worldwide cast of bus passengers, 24-hours a day. If it were not for the number 149 I wouldn’t have passed by the Geffrye Museum. This marvellous museum has provided the ideal preparation for Brimstone and Treacle. As a “museum of English homes and gardens”, it is filled with stage-set interiors charting a chronological sweep through English domestic history. The Bates’ morose middle class abode of the mid-1970s would fit in beautifully as one of the room sets of the Geffrye Museum. These museumified interiors confirm our collective obsession with “home”. Many people share the sentiments of Mr Bates: they long for a private refuge from the world flanked by a neat little garden and a street outside filled with safe-and-sound old ladies. Of course, these exact same private paradises are all too often the setting for all manner of barbarisms perpetrated by “sweet talking rapists at home”.(1) The domestic sphere is, then, a potent mixture of brimstone and treacle. Dennis Potter makes this shockingly apparent in his brilliant play of that title. I really hope that the Arcola Theatre does justice to Potter’s helping of demonic hospitality. ___ Note (1) The Blow Monkeys, “Sweet Talking Rapist at Home”, Whoops! There Goes the Neighbourhood, 1989, RCA. |

Para, jämsides med.

En annan sort. Dénis Lindbohm, Bevingaren, 1980: 90 Even a parasite like me should be permitted to feed at the banquet of knowledge

I once posted comments as Bevingaren at guardian.co.uk

Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

_

Note All parasitoids are parasites, but not all parasites are parasitoids Parasitoid "A parasite that always ultimately destroys its host" (Oxford English Dictionary) I live off you

And you live off me And the whole world Lives off everybody See we gotta be exploited By somebody, by somebody, by somebody X-Ray Spex <I live off you> Germ Free Adolescents 1978 From symbiosis

to parasitism is a short step. The word is now a virus. William Burroughs

<operation rewrite> |

key words: architecture | archive | art | commemoration | design | ethics | framing | freedom of speech | heritage | heroes and villains | history | illicit trade | landscape | media | memorial | memory | museum | music | nordic | nottingham trent university | parasite | politics | science fiction | shockmolt | statue | stuart burch | tourism | words |