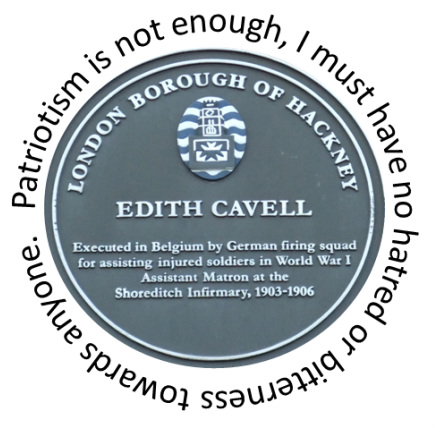

"I arrive for the first time in London and take walks with different companions… Even if I were unaccompanied, I need only have read their varying descriptions of the city, been given advice on what aspects to see, or merely studied a map. Now suppose I went walking alone. Could it be said that I preserve of that tour only individual remembrances, belonging solely to me? Only in appearance did I take a walk alone. Passing before Westminster, I thought about my historian friend's comments (or, what amounts to the same thing, what I have read in history books). Crossing a bridge, I noticed the effects of perspective that were pointed out by my painter friend (or struck me in a picture or engraving). Or I conducted my tour with the aid of a map. Many impressions during my first visit to London – St. Paul's, Mansion House, the Strand, or the Inns of Court – reminded me of Dickens' novels read in childhood, so I took my walk with Dickens. In each of these moments I cannot say that I was alone, that I reflected alone, because I had put myself in thought into this or that group… Other men (sic) have had these remembrances in common with me. Moreover, they help me to recall them. I turn to these people, I momentarily adopt their viewpoint, and I re-enter their group in order to better remember. I can still feel the group's influence and recognize in myself many ideas and ways of thinking that could not have originated with me and that keep me in contact with it."

Maurice Halbwachs, The Collective Memory, trans. F.J. Ditter Jr and V. Yazdi Ditter (New York: Harper & Row, 1980), pp. 23-24.