Janelle Monáe, 'Sally Ride', The Electric Lady, 2013

|

Tell me who can I trust? I wanna fly to the stars.

Janelle Monáe, 'Sally Ride', The Electric Lady, 2013  Earlier today I carried out some contemporary archaeology. The site of excavation was Nottingham’s branch of Modelzone. This toy and hobby retailer has gone into administration and all eighteen of its remaining stores will close over the coming weeks.(1) Today it was the turn of the outlet at Broadmarsh shopping centre. Its demise is part of the terminal decline of this much-derided mall. Back in January I watched the last death throes of shoe emporium Gordon Scott.(2) This had occupied a unit adjacent to Modelzone ever since Broadmarsh opened in the 1970s. Nowadays customers in search of footwear must exit the mall and make their way to Lister Gate. The closure of Modelzone is worth recording, not least as a reminder that over 500 people have lost their jobs following the company’s liquidation.(3) Given that they are now things-of-the-past, all manner of quotidian Modelzone-related artefacts have suddenly accrued heritage-value. Thus the till receipt recording my last purchase plus the plastic carrier bag with its Modelzone logo merit preservation in preparation for their future museum-status. My choice of purchase on this final day was deliberate. It involved a box of British paratroopers from the Falklands War, lovingly sculpted in plastic in a scale of 1:76. It seemed appropriate to buy these tokens of a post-imperial (sic) military adventure just as Britain is on the cusp of war with a new foreign enemy. (But see Supplemental note below.)  But not all Britons are as enthusiastic for another Middle East campaign as the current British government.(4) Upon leaving Broadmarsh I headed for Old Market Square. At “Speakers’ Corner” I came across a small band of protestors, urging the people of Nottingham to join them in opposing any British involvement in Syria’s bloody civil conflict. One thing seems certain, however. If British soldiers do engage this new foe, it will no doubt lead to the production of more model soldiers. One day it will become possible to purchase items from the range marked: “British Paratroopers (Syria War, 2013-?)” We shall have to acquire them from an online store, of course given that soon the notion of physical shops on something that used to be known as “the high-street” will be a quaint, nostalgic Woolworths-sweet-wrapped memory (the last bag of which sold on eBay for a reported £14,500 (5)). ___ Notes (1) Simon Neville, “Modelzone toy retailer collapses after failure to find buyer”, The Guardian, 28/09/2013, http://www.theguardian.com/business/2013/aug/28/modelzone-collapses-deloitte-fails-buyer. (2) Stuart Burch, “Respect for the Riddler”, 27/01/2013, http://www.stuartburch.com/1/post/2013/01/respect-for-the-riddler.html. (3) Neville, op cit. (4) “Syria crisis: David Cameron makes case for military action”, 29/08/2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-23883427. (5) “Last ever bag of Woolworths pick 'n' mix sweets sells for £14,500 on eBay”, Daily Mail, 21/02/2009, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1151542/Last-bag-Woolworths-pick-n-mix-sweets-sells-14-500-eBay.html. Supplemental

30/08/2013 Cancel that box of toy soldiers! In a rare outbreak of democracy, the Westminster parliament has put a temporary halt to a British foreign policy formulated in Washington DC.(1) Can it really be that, at long last, “Britain's illusion of empire is over”?(2) Only time will tell. But for now at least let us savour the true taste of Tony Blair’s political legacy. (1) “Syria crisis: Commentators react to Cameron defeat”, BBC News, 30/08/2013, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-23894749. (2) Polly Toynbee, “No 10 curses, but Britain’s illusion of empire is over”, The Guardian, 29/08/2013, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/aug/29/no-10-curses-but-empire-is-over. Margaret Thatcher has passed into history.

How should she be remembered? Through her encounter with Diana Gould (1926-2011). Mrs Gould exposed the real Margaret Thatcher. Belligerent, disdainful, hectoring, bullying, intransigent. All things that should be consigned to history. “Where there is discord, may we bring harmony...”

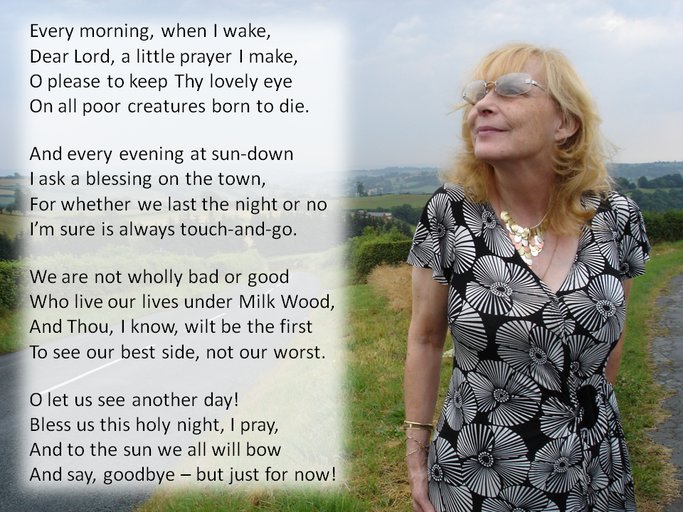

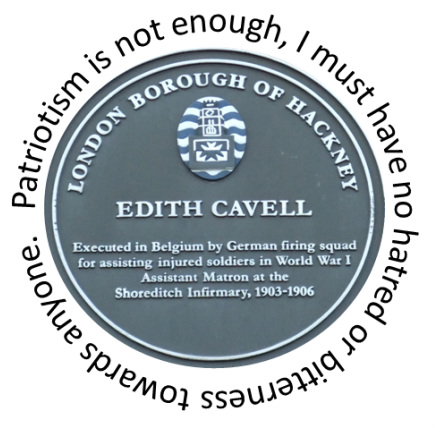

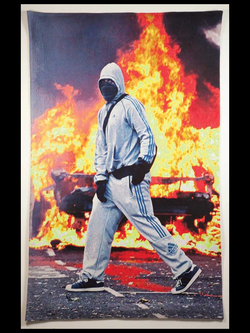

These words of St. Francis of Assisi were cited by Margaret Thatcher on the steps of Number 10 Downing Street on Friday 4th May 1979 – the day she took office as the first female prime minister of Great Britain. Mrs Thatcher went on to add some thoughts of her own: “and to all the British people – howsoever they voted – may I say this. Now that the Election is over, may we get together and strive to serve and strengthen the country of which we’re so proud to be a part.”(1) This is indicative of a paradox that runs right through Thatcher’s long and eventful period in power. Those who laud her achievements urge her detractors to accept that, whilst they might not have agreed with her politics, she should be admired as a great patriot with a “lion-hearted love for this country”. That was how David Cameron characterised her on the day she died. He chose to deliver his eulogy on the spot from where his predecessor addressed the media back in 1979. Nevertheless, at the same time as praising the person he regarded as “saving” the country, Cameron added: “We can’t deny that Lady Thatcher divided opinion.” He insisted, however, that Thatcher “has her well-earned place in history and the enduring respect and gratitude of the British people.”(2) It is characteristic of Mr Cameron that he should deliver such a contradictory statement. If Thatcher “divided opinion” how can “the British people” be of one mind? And if she loved Britain so much, how could Thatcher encourage a climate in which some Britons prospered and thrived at the expense of others? This continues to pose a problem now that she is dead. How should she be memorialised? Bear in mind that a statue erected in her lifetime has already been decapitated by an irate “patriot”.(3) An early opportunity to test the public mood will come during the ceremony leading to her cremation. Whilst she will not be given a state funeral, she will be accorded a military procession to St Paul’s Cathedral. During that parade all manner of socialists, former miners, Irish nationalists, Argentines, anti-Apartheid veterans, LGBT campaigners and others might seek to pay their final respects in ways that will subvert David Cameron’s confident assertion regarding Thatcher’s “place in history and the enduring respect and gratitude of the British people.” Once the funeral is over thoughts will turn to a more permanent commemoration. At that point the Iron Lady will be transmogrified into bronze. The obvious place to site such a memorial is Parliament Square.(5) There she can surmount a pedestal alongside the petrified Churchill and generate an interesting dialogue with the statues of two South Africans, Jan Smuts and Nelson Mandela. Thatcher’s opposition to international sanctions against Apartheid South Africa – plus her hostility to German reunification – are reminders that differences of opinion over her legacy are not confined to England, Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. In each of these areas one can cite a litany of issues that remain contentious today, from the North-South divide in England to the piloting of the Poll Tax in Scotland, the decimation of the industrial communities of South Wales and her administration’s secret negotiations with the IRA in stark contrast to Thatcher’s publicly stated position. It seems inevitable that an official memorial to Lady Thatcher will be erected in the not-too-distant future. All too often such commemorations pretend to be natural occurrences that are universally supported. That lie will be impossible to sustain in this particular instance. A literal Iron Lady will confirm an observation made by Kirk Savage: “Public monuments do not arise as if by natural law to celebrate the deserving; they are built by people with sufficient power to marshal (or impose) public consent to their erection.”(4) Waves of attacks will be unleashed on any tangible memorial to Thatcher. These will be dismissed as vandalism or accepted as iconoclasm depending on one’s point of view. But the daubs of paint or attempts at decapitation will confirm one thing. Mrs Thatcher achieved much, but by her own measure she failed in at least one regard. She came to office urging Britons to “get together” and help her “bring harmony”. Yet her enduring legacy is division and discord. And that’s something that even David Cameron cannot deny. ----- Notes (1) Margaret Thatcher, “Remarks on becoming Prime Minister (St Francis’s prayer)”, 04/05/1979, http://www.margaretthatcher.org/speeches/displaydocument.asp?docid=104078 (2) Steven Swinford & James Kirkup, “Margaret Thatcher: Iron Lady who made a nation on its knees stand tall”, Daily Telegraph, 08/04/2013, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/margaret-thatcher/9980285/Margaret-Thatcher-Iron-Lady-who-made-a-nation-on-its-knees-stand-tall.html (3) The perpetrator was Paul Kelleher, a thirty-seven year old theatre producer. His justified his actions by claiming that the attack was in protest against global capitalism. See Stuart Burch, On Stage at the Theatre of State: The Monuments and Memorials in Parliament Square, London (A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, March 2003), pp. 350-351. (4) Kirk Savage, “The politics of memory: Black emancipation and the Civil War monument”, in John R Gillis (ed.), Commemorations: the politics of national identity, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 135. (5) This was something that I called for a decade ago: “An image of Margaret Thatcher in the sacred yet so vulnerable domain of Parliament Square would infuse it with ‘living power’. For the statue, taking its rightful place alongside Churchill, would be finely posited between veneration and disdain and then, in the fullness of time, between neglect and ignorance.” Burch, On Stage at the Theatre of State, 2003, p. 351.  I have been disrupted twice in the last couple of days. On both occasions the disruption has been presented to me as positively welcome – something to celebrate. The first disturbance arose during a talk about MOOCs. This acronym stands for massive online open courses. Their proponents claim these to be the-next-big-thing in education. Old fashioned universities beware: soon they’ll be superseded by entirely online providers charging a fraction of the price and servicing hundreds of thousands of participants drawn from the four corners of the globe. This is all thanks to disruptive technologies: IT innovations that disturb the status quo as surely as music downloads have annihilated the high-street record store. Be that as it may, listening to a gorgeously slick gentleman from a posh US university preaching about disruption made me suspicious. Don’t be lulled into thinking that this particular brand of commotion is inherently exciting, radical or open. Because that would be to belie the imperialistic ambitions of many of the organisations that lurk beneath the mantle of disruptive technology. The next day also proved to be cheerfully disruptive. On this occasion the challenge to the natural order occurred towards the close of a highly civilized seminar hosted by the Arts and Humanities Research Council. Representatives of groups funded by the AHRC’s various knowledge exchange schemes were invited to meet in Bristol and share ideas. One participant happened to mention how her scheme had helped facilitate “disruptive thinking”. This in turn got me thinking disruptively. To what extent do funders tolerate such behaviour? Moreover, “disruptive thinking” is promoted because it can lead to failure. But it would take a bold person to declare in an end-of-project-report that their research was brilliantly abortive, that they didn’t bother doing what they had promised and had in fact consciously subverted the aims of the funding organisation: all in the name of disruptive thinking. Would such disruptions be welcome? Would they lead to renewed investment from a grateful funding body? Bear in mind that these sources of money must also be accountable to a board of trustees, some government department or the largess of a tax avoiding business. I pondered these things whilst making my way to Bristol Temple Meads to catch my train back to snowy Nottingham. Suddenly I looked up and – to my surprise – found myself in the midst of a ferocious riot. Sword-wielding soldiers on horseback were pitching into a crowd of angry protestors. Such was the ferocity of this incident that I was mighty pleased to have turned up after it had started. Precisely 182 years after.  The incident in question was taking place in a large mural painted on the backdrop to a patch of rough ground adjacent to the Bath Road. It commemorates the Reform Bill riots that took place in Bristol’s Queen Square in 1831. This disturbance has a resonance in the city to which I was headed. In Nottingham similar acts of insurrection also took place in 1831. On 10th October a crowd of residents, frustrated by the lack of progress towards electoral reform, gathered in Market Square before heading up the hill to the site of the old Nottingham castle, then the home of the dukes of Newcastle. They burnt the mansion to the ground. It stayed that way for fifty years until the gutted shell was transformed into a municipal museum and art gallery. The fullness of time has turned the disruptive events of 1831 into local histories. They are also part of a neat linear story of political change leading to universal suffrage. But would the imperfect democracy enjoyed by Britons today have been achieved if some individuals weren’t prepared to disrupt the present order? And wouldn’t it be ironic if these disruptive deeds were to one day become the subject matter of some not-for-profit (sic) MOOC or even a British knowledge exchange initiative? Goodness, what a disruptive thought! The third one this week!  Marc Quinn, The Creation of History (2012) Marc Quinn, The Creation of History (2012) On Thursday 4th August 2011 officers of the Metropolitan Police Service stopped a taxi on Ferry Lane in Tottenham Hale, London. Its occupant – Mark Duggan – was subsequently shot dead in uncertain circumstances. This single incident gave rise to a spate of riots across England. The worst scenes took place in the capital. A defining image of that summer of violence is a photograph taken by the Turkish born photojournalist, Kerim Okten. It shows a man in a grey tracksuit and trainers. The skin on his hands is covered by black gloves. His face is veiled by a mask such that only his eyes are visible: they gaze fixedly at the camera lens. Framing that stare are the orange flames and choking black smoke of a burning vehicle. Various versions of this iconic scene are available online. They differ in all sorts of major and minor ways. Some depict the main protagonist in alternative poses; others show bystanders looking on at the searing shell of the car. Text invariably accompanies the picture wherever it appears. A front page headline such as “The battle for London” turns this masked celebrity into a capital warrior. Replace that caption with something like “Yob rule” and our battle-scarred warrior becomes a mindless hoodlum. His slow, purposeful steps and cold stare do indeed make this lord of misrule appear above the law. The rights to Okten’s image have now been acquired by the British artist Marc Quinn. He has used it as the inspiration for a variety of artworks including paintings, a sculpture and even a tapestry. The latter has been entitled The Creation of History (2012) and exists in an edition of five. The title chose by Quinn reflects his belief that the 2011 riots constitute “a piece of contemporary history”. The artist is quick to add, however, that this history – like every past event – is “a complex story and raises as many questions as it [does] answers. Is this man a politically motivated rioter? A looter? What is in his pocket? And rucksack? More intriguingly, the mask he wears appears to be police-issue: could he even be a policeman?”(1) The merest suggestion that our photogenic “yob” might in fact be a lawgiver rather than a lawbreaker disturbs this already troubling image, transforming it before our very eyes. This is exacerbated further in Quinn’s tapestry transmutation. Metamorphosing the pixels of a digital photo into the knots of a woven image catapults this contemporary history back in time. Now our “yob” can stand alongside armour-suited warriors in a medieval pageant. The rich heritage of Quinn’s The Creation of History makes it worthy to enter into the sacred realm of the museum. And what better institution than Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery? This establishment rose like a phoenix from the flames of a riot: on 10th October 1831 a group of rabble-rousers intent on creating a little history of their own torched the palatial home of the Duke of Newcastle in protest at his opposition to electoral reform. For fifty years the burnt out shell of the building remained an admonitory reminder of this bad behaviour. Then, in the 1870s, it was converted into the first municipally funded museum outside of London. This place of learning and leisure still stands. And it only exists thanks to the sort of scenes that were to take place 180 years later – not only in London but also Nottingham, where Canning Circus police station was firebombed by tracksuited warriors / yobs. So, with this in mind, wouldn’t it make perfect sense for the curators at Nottingham Castle Museum to acquire one of the five editions of Marc Quinn’s The Creation of History? It could hang on the same walls that were once covered by tapestries – before “yob rule” led to them being unceremoniously ripped down and either burnt or “sold to bystanders at three shillings per yard.”(2) ___ Notes (1) Cited in Gareth Harris, “London riots get tied up in knots”, The Art Newspaper, Iss. 243, 07/02/2013, accessed 08/02/2013 at http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/quinn-tapestry/28545. (2) Harry Gill, A Short History of Nottingham Castle (1904), available at, http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/gill1904/reformbill.htm._ The sunset poem of the Reverend Eli Jenkins. (1) In memory of Barbara Ann Burch. “Remember her. She is forgetting.” (2) (1) Dylan Thomas, Under Milk Wood, London: Dent, 1995, pp. 57-58.

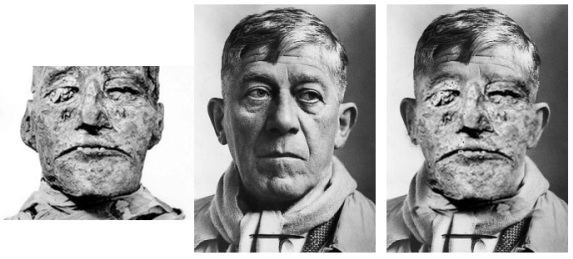

(2) Under Milk Wood, p. 52.  History today according to the BBC The front page of today’s BBC news website reveals a great deal about how historical events impinge on the present. This needs to be seen as indicative of a widespread obsession with the past. But it shouldn’t make us overlook the fact that the primary interest is current affairs. Simply put, history needs to have some contemporary resonance in order to count as “news”. This is the case with the deaths of two men in their 90s. Their passing is, of course, a personal loss to their friends and relatives. I never knew them, but I am invited to pay my respects because these two gentlemen feature in the collective consciousness. This is due to two events that form part of the national story, namely the Jarrow March of 1936 and the experiences of Britons incarcerated overseas during the Second World War. The demise of Con Shiels (the last survivor of the Jarrow March) and Alfie Fripp (a veteran of no fewer than twelve POW camps) marks the moment when two iconic occurrences pass from lived experience to “history”. This liminal moment gives the past a special frisson. We watch as the final living link to a momentous event is broken. This is history in the making. There are lots of other issues that flow from these particular stories. Is history made by the many or the heroic (or villainous) few? Can we learn from “everyday heroes” like Con Shiels and Alfie Fripp? If so, what part (if any) do we play in history? And what actually counts as a historical event? How influential was the Jarrow March? Did it change the course of history? Or is its significance given undue importance by subsequent commentators? In the BBC’s report of the death of Con Shiels it is notable that the trade unionist, Steve Turner is quoted calling for a “new ‘rage against poverty’”. Similarly, in 2011 the Jarrow March was re-enacted to mark its 75th anniversary and draw attention to youth unemployment. This demonstrates how a historical “fact” is nothing without interpretation. And this makes it inevitable that the politics of the present will get woven into the patterns of the past. The Jarrow example provides a flavour of things to come. Get ready for the bickering and arguing that will be triggered when Margaret Thatcher dies! The shadow of the Iron Lady looms large over another historically-flavoured news story: the status of the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas). This latest episode relates to Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s open letter to British prime minister, David Cameron in which she decries the continuance of “a blatant exercise of 19th-century colonialism” and calls for a negotiated solution as urged by the General Assembly of the United Nations way back in 1965. Interestingly enough, one of the BBC web links connected to de Kirchner’s rhetorical salvo refers to new documents released under the British government’s 30-year rule. These reveal just how surprised Thatcher was by the Argentine invasion. Access or restrictions concerning such primary evidence play a crucial role in determining how history gets written and re-written. Another link stemming from the latest crisis facing the Falkland Islands reminds us of the glorious / tragic events of 1982 via the commemorative events marking the thirtieth anniversary of the end of the Anglo-Argentine war. An anniversary such as this represents an additional way in which the past enters the present. The commemorative re-enactment of the Jarrow March is a case in point. A further example is to be seen amongst today’s crop of news stories, namely the centenary of Rhiwbina garden village in Cardiff. But what about events of today that are destined to become tomorrow’s history? Well, the year that has just passed has gone down in the record books as the “second wettest on record”. There is reason to believe that this will soon be surpassed, with reports that “extreme rainfall” is on the rise. And this is an appropriately apocalyptic note to end this account of history today. Because one of the factors motivating our love of the past is a widespread anxiety about the future. History’s near cousin is nostalgia. Poverty, unemployment and war take on a rosy hue thanks to the patina of time. Using the vantage point of the present we know that things worked out alright in the end... Or did they? New research seems to confirm what many have long suspected: King Ramesses III was murdered, probably by having his throat cut sometime around the year 1155BC. This is reported by the BBC alongside a small photograph of the king’s mummified visage.(1) He looks strangely familiar... and then it struck me how much he reminds me of the late, great expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka. I wonder if their DNA crossed at some point over the past few millennia?

___ Note (1) Michelle Roberts, “King Ramesses III’s throat was slit, analysis reveals”, BBC News, 18/12/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-20755264  On Sunday 11 November a fascinating debate took place at Arkitekturmuseet (Sweden’s national museum of architecture). It marked the culmination of a weekend of activities to celebrate the institution’s fiftieth anniversary. Events included guided tours of the Rafael Moneo-designed building which Arkitekturmuseet shares with another of Sweden’s state museums, namely Moderna Museet. The highlight of the festivities focused on the commemorative publication, The Swedish Museum of Architecture: A Fifty Year Perspective. This was launched following a series of reflections by two contributors to the book, Thordis Arrhenius and Bengt O.H. Johansson (the latter was director of the museum from 1966-77). This was followed by a panel debate entitled “Midlife crisis or stroppy teenager? A discussion about Arkitekturmuseet yesterday, today, tomorrow”.(1) It was at this point that matters started to get interesting. It quickly became apparent that the past, present and future of Arkitekturmuseet are far from settled. Much attention was given to the recently expanded role of the museum. This is summed up in an introductory section of the anniversary book. Under the rubric, “More than a museum”, Monica Fundin Pourshahidi cites a press release by the Swedish minister of culture, Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth in which it is stated that, from 2009 onwards, Arkitekturmuseet is vested with being a “power centre” not only for architecture but also for design: “The Museum of Architecture can and must be a display window and a distinct voice in the debate on social planning, architecture, design and sustainable development”.(2) This point was taken up by Arkitekturmuseet’s present director, Lena Rahoult. But her positive spin was immediately problematised by a fellow panel member, the architectural historian Martin Rörby. The focus of his criticisms was a recent governmental memorandum which instructed the institution to engage in “promotion and communication” (främjande och kommunikation) rather than “traditional museum activities” (traditionell museiverksamhet). This would be best signalled by a change in title, with the word “museum” being replaced by “centre” or “arena”.(3) Rörby expressed reservations about such a shift in focus, fearing that an increase in breadth would come at the expense of depth and critical engagement. He was also troubled by the vague, empty rhetoric of the memorandum. On the other hand, the notion of going beyond what was expected of a “traditional” museum was nothing new. Rörby illustrated this point by citing Arkitekturmuseet’s past involvement in the often heated debate regarding Sergels torg in central Stockholm. He stressed the rapidity of the museum’s response which enabled it to react to a pressing, contemporary issue. This active engagement, however, was only possible because of the museum’s unrivalled collections of artefacts, architectural models and other archival documents. Rörby was of the opinion that the museum would find it far harder – if not impossible – to arrange such an exhibition in the additional field of design. This is because the museum responsible for the national design collection is another entirely separate institution, namely Nationalmuseum. The design holdings will remain there, despite Arkitekturmuseet’s increased mandate. In the light of this one can be forgiven for questioning the basis for adding design to the museum of architecture. The oddness of this situation was beautifully demonstrated by the fact that, at the very same time that this debate was unfolding at Arkitekturmuseet, Nationalmuseum just down the road was holding a “theme day” on “handicraft, time and creativity” in association with its craft and design exhibition, Slow Art.(4) Way back in the late 1980s and early 1990s the museum fraternity in Sweden dreamed of a museum of industrial design (Konstindustrimuseet) being housed in Tullhuset adjacent to the main Nationalmuseum building in the Blasieholmen area of Stockholm. This nineteenth century toll house was to have been expanded to allow for 5000 square metres of exhibition space. Alas, this imaginative idea proved abortive, as did a plan to deploy the spectacular Amiralitetshuset on the island of Skeppsholmen.(5) In the wake of these failed initiatives comes the current half-baked decision to place the design burden on the ill-equipped museum of architecture. Meanwhile, in February 2013, Nationalmuseum will close for a period of four years during which time a multi-million kronor refurbishment will take place. This, one would have thought, would be the ideal opportunity to resolve the status of design in Sweden. The risk is that the investment in Nationalmuseum is being made against a contested, confused and contradictory context. Exacerbating this frankly farcical state of affairs is the added complication of Arkitekturmuseet’s relationship with Moderna Museet. These two museums, as has been noted, share a building. One might therefore have thought that it would sensible for the pair to unite, especially given the enlarged remit of Arkitekturmuseet. Indeed, in 1998 it was proposed that modern design dating from 1900 onwards should be moved to Moderna Museet.(6) On being asked about the relationship with her neighbour, Arkitekturmuseet’s director Lena Rahoult made a few platitudinous comments and paid compliments to Daniel Birnbaum, her counterpart at Moderna Museet. However, when it comes to Moderna Museet’s upcoming exhibition on Le Corbusier, it emerged that the museum of architecture will not be involved.(7) This, it strikes me, represents a potentially serious threat to the autonomy of Arkitekturmuseet. If the Le Corbusier exhibition is a success despite (or perhaps because of) the exclusion of Arkitekturmuseet, then the argument is being made that Moderna Museet is more than capable of taking over this field. Daniel Birnbaum would no doubt be delighted. He is a very shrewd operator. Upon taking over the running of Moderna Museet he erased all trace of its former director in the most charming manner: by turning the whole museum over to photography. This had a number of consequences. It facilitated a tabula rasa whilst showing Birnbaum to be both innovative and in step with the history of the museum. This in turn stifled any potential suggestion that photography was not being accorded sufficient attention. This was a smart move given that the formerly separate museum of photography had been subsumed into the collections of Moderna Museet on the completion of Rafael Moneo’s building in 1998. With this potential criticism snuffed out, Birnbaum then set about curtailing the independence of the museum’s satellite institution, Moderna Museet Malmö. This was led by Magnus Jensner until a “restructuring” made his position untenable and prompted his resignation.(8) In March of this year Jensner was succeeded by Birnbaum’s man in Stockholm, John Peter Nilsson. Against the background of these strategic manoeuvres the decision to mount an exhibition on Le Corbusier at Moderna Museet is no mere innocent happenstance. It can be interpreted as part of a calculated empire building process. And, if the recent debate at Arkitekturmuseet is anything to go by, Birnbaum is a giant among pygmies on the Swedish cultural scene. Perhaps mindful of this, at the same time as spouting her platitudes, Lena Rahoult has been busy mounting the barricades. She has taken the decision to withdraw Arkitekturmuseet from the bookstore that it has shared with Moderna Museet since the inception of Moneo’s building. All the books are being sold at a reduction of 60% whilst magazines and postcards are being flogged off for a few kronor. Once this stock has been disposed, Arkitekturmuseet will open a separate retail establishment in its own part of the locale. This development is notable given that the bookstore was one of the very few aspects of the building where the two institutions merged. Another is the shared ticket desk. Moneo designed the building to incorporate the old drill-hall where Moderna Museet began life and which is now occupied by Arkitekturmuseet. In so doing he provided a new entrance and closed the original doorway. Rahoult plans to reopen this entrance whilst keeping the other in use. Birnbaum is on record as describing this proposal as “ludicrous” (befängd).(9) Well he might, because one of the main criticisms of Moneo’s building is its very modest and hard-to-find entrance. Should Arkitekturmuseet prove to be the main gateway into the combined museum it may well increase the number of visitors to the architecture collection, but it will draw attention from what is currently the dominant partner, Moderna Museet. The proposed changes to the shop and entrance have led to claims that Arkitekturmuseet wishes to “break free from Moderna Museet”.(10) The paradoxical situation has therefore arisen whereby, at the same time that Arkitekturmuseet struggles to work across disciplines in one direction, it is placing barriers to the museum next door. There is, of course, no reason why different disciplines should not be brought together in a single museum. A case in point is the Museum of Modern Art, MOMA. Its mission statement is grounded in the belief [t]hat modern and contemporary art transcend national boundaries and involve all forms of visual expression, including painting and sculpture, drawings, prints and illustrated books, photography, architecture and design, and film and video, as well as new forms yet to be developed or understood, that reflect and explore the artistic issues of the era.(11) Another example closer to home is Norway. However, in this case the forced union of art, architecture and design has been far from amicable or straightforward. But at least Norway’s National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design is being given a grand new building in which to unite. This is not the case in Sweden. No one should be surprised about this given the paltry cultural policies of the present alliance government under the stewardship of its mediocre minister of culture, Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth. When it came to the festivities to mark Arkitekturmuseet’s jubilee debate, the icing on the birthday cake occurred when the panel turned to the audience for questions and response. Up stepped Jöran Lindvall. He remains – as he was at pains to make clear – the longest serving director of Arkitekturmuseet (during the years 1985-1999). Nevertheless, he added pointedly, no one had thought to ask him to contribute to the fiftieth anniversary publication. His absence from its pages was a timely reminder that such official records are as partial as they are political. That much is shown by a similar publication released to mark Moderna Museet’s own fiftieth anniversary in 2008. Such historical tomes might seem to be rooted in the past, but their main aim is to seek to placate the politicised present whilst simultaneously shaping the uncertain future. As if to underline this, Jöran Lindvall presented the current holder of the post he once occupied with a bag stuffed full of newspaper cuttings and other documents from his private collection relating to exhibitions that took place during his time at the museum. He declared his willingness to donate these to Arkitekturmuseet, but on one condition: that it remain a museum devoted to architecture. Lena Rahoult accepted this generous offer. She could hardly do otherwise. It will be interesting to follow the fate of Lindvall’s loaded gift. Indeed, all those involved in museums would do well to keep track of events in Sweden and watch with interest as commentators, practitioners, museum professionals and politicians plot their next moves in a battle that is more comedy than tragedy. But that is not to say that the outcome is likely to leave very many people laughing. _____ Notes (1) The panel participants were the director of Arkitekturmuseet, Lena Rahoult together with Fredrik Kjellgren (architect), Petrus Palmér (designer), Birgitta Ramdell (director of Form/Design centre, Malmö) and the architectural historian Martin Rörby (Skönhetsrådet). The chair was Kristina Hultman. (2) Press release dated 19 December 2008, cited in Main Zimm (ed.) The Swedish Museum of Architecture: A Fifty Year Perspective, Stockholm: Arkitekturmuseet, p. 4. (3) Cited in “Stora förändringar föreslås på Arkitekturmuseet”, Arkitektur, undated, http://www.arkitektur.se/stora-forandringar-foreslas-pa-arkitekturmuseet (accessed 12/11/2012). (4) Slow Art, Nationalmuseum, 10 May 2012 – 3 February 2013. The special event that took place on Sunday 11 November included a talk by Cilla Robach (“Slow Art – om hantverk, tid och kreativitet”) followed by a craft activity for children (see the advertisement on p. 7 of the Kultur section of that day’s issue of the newspaper, Dagens Nyheter). (5) Mikael Ahlund (ed.) Konst kräver rum. Nationalmuseums historia och framtid, Nationalmusei skriftserie 17, 2002, pp. 76-77. (6) Ahlund, 2002, p. 77. (7) Moderna Museet’s exhibition has been given the name “Moment – Le Corbusier’s Secret Laboratory” and will run from 19 January – 28 April 2013. The decision not to collaborate with Arkitekturmuseet is ironic given that the latter put together the exhibition “Le Corbusier and Stockholm” in 1987. (8) “Magnus Jensner slutar i Malmö”, Expressen, 20/10/2012, http://www.expressen.se/kvp/magnus-jensner-slutar-i-malmo. (9) “Arkitekturmuseets femtioårskris – en intervju”, Arkitektur, undated, http://www.arkitektur.se/arkitekturmuseets-femtioarskris-en-intervju (accessed 12/11/2012). (10) Hanna Weiderud, “Arkitekturmuseet bryter sig loss från Moderna”, SVT, 01/11/2012, http://www.svt.se/nyheter/regionalt/abc/arkitekturmuseet-bryter-sig-loss-fran-moderna. (11) Collections Management Policy, The Museum of Modern Art, available at, http://www.moma.org/docs/explore/CollectionsMgmtPolicyMoMA_Oct10.pdf.  Yesterday a group of people gathered in Custom House Square, Belfast. They then opened three large freezers, removed 1,517 diminutive frozen figures and began placing them around the square. When the task was complete they stood back and spent the next twenty minutes watching as these human icicles melted before their eyes. This happening was part of a festival to mark the centenary of the sinking of the RMS Titanic. The person responsible for this particular commemorative response was the Brazilian born artist, Néle Azevedo (born 1950). Her poignant idea was entitled, Minimum Monument. It was intended as a celebration of the “ephemeral and diminutive, as opposed to what is monumental and grandiose.”(1) For instances of the “monumental and grandiose” one might turn to John Blackwood’s book London’s Immortals: The complete commemorative outdoor statues (Savoy Press, 1989). The cover features an individual who exudes monumentality and grandiosity. This is all the more remarkable given that the person being represented is physically frail – so weak in fact that he requires a walking stick to support his gargantuan frame. But his greatness comes from the courage of his convictions rather than the strength of his sinews. The bronze effigy commemorates a man who is seemingly so famous that he requires no elaborate inscription. On the pedestal on which he is placed is but a single word: Churchill. Statues of this nature are intended to create the illusion of universal acclaim and permanence. This façade came crashing down during my investigations into this sculpture and the other commemorative monuments that surround the Houses of Parliament in London. In the year 2000 a riot broke out where the natural order was inverted: protestors mounted Churchill’s plinth and daubed it with graffiti. In the process they turned the war hero into a bloated warmonger. For a short time this establishment figure became a punk icon (courtesy of the grass mohican draped over his pate).(2) I wonder what the late, great playwright and author, Dennis Potter would have made of such bad behaviour? I ask because, way back in 1967 in one of his earliest plays for television, Potter took a “swipe at Churchillianism”.(3) Alas, the original recordings of this and two other such works were subsequently deleted by the BBC. Years later Potter reflected on his vanished play. He dismissed it as “polemical” and “overtly political”, something with which now felt uncomfortable.(4) We are not in a position to judge if he was right to be so self-critical given that the work no longer exists. This makes the title of the play deeply ironic. It was called, Message for Posterity. That phrase sums up Ivor Roberts Jones’s titanic statue of Churchill that has scowled at parliament ever since its inauguration in 1973. But messages for posterity do not always have to be like this. They can be more modest and far less bombastic – like Néle Azevedo’s already vanished tribute to the 1,517 lives cut short when the monumental and grandiose prow of the Titanic sank beneath the icy waves of the North Atlantic Ocean. ____ Notes (1) Nuala McCann, “Poignant ice tribute to Titanic victims”, BBC News, 21/10/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-20020498 (2) For more about this, see my doctoral thesis, On Stage at the Theatre of State: The Monuments and Memorials in Parliament Square, London (A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, March 2003). (3) Graham Fuller (ed.), Potter on Potter, London, Faber and Faber, 1993, p. 17. (4) Potter on Potter, pp. 31-32.  The British Museum possesses many thousands of fascinating objects. One of its self-styled “highlights” is a rather plain looking marble inscription. It comes from Rome and is dated around AD 193-211. What makes it so interesting are the things it does not show. These include the names of two relatives of the Roman emperor, Septimius Severus (AD 145-211), namely his daughter-in-law Plautilla and his son Geta. The latter was murdered by Septimius Severus’ other son Caracalla. He was Plautilla’s husband and Geta’s brother. The two siblings were bitter rivals following the death of their father. It is believed that Caracalla murdered Geta and then had his treacherous and much despised wife executed. And, to make matters even worse, they were then subjected to the posthumous punishment of damnatio memoriae: their names were expunged from all official records and inscriptions and their statues and all images of them were destroyed. This process [damnatio memoriae] was the most horrendous fate a Roman could suffer, as it removed him from the memory of society.(1) However, removing Geta from public consciousness was not a straightforward matter. Caracalla was obliged to give his brother a proper funeral and burial due to Geta’s popularity both with the Roman army and among substantial sections of Roman society. This explains why the names of Geta and Plautilla were included on the British Museum’s marble inscription, only to be scratched out later on. Why am I mentioning all this? Because a modern-day form of damnatio memoriae is currently unfolding in British society. This is in relation to the disc jockey, children’s television presenter and media celebrity, Sir Jimmy Savile OBE, KCSG, LLD (1926-2011). When he died last year at the ripe old age of 84 he was hailed a loveable hero who had done much for charity. Now, however, revelations have come to light suggesting that he was, in the words of the police, a “predatory sex offender”.(2) As a result, strenuous efforts are being made to expunge him from the public record.(3) Thus, the charity that bears his name is considering a rebrand. A plaque attached to his former home in Scarborough was vandalised and has since been removed. So too has the sign denoting “Savile’s View” in the same town. Meanwhile, in Leeds, his name has been deleted from a list of great achievers at the Civic Hall. A statue in Glasgow has been taken down in an act of officially sanctioned iconoclasm. The same fate has been dished out to the elaborate headstone marking Savile’s grave. This last-named act of damnatio memoriae is in some ways a pity given the unintended poignancy of the epitaph inscribed on the stone: “It Was Good While It Lasted”. It was almost as if Savile knew that he would one day have to atone for his evil deeds. Atonement has, alas, come too late for those that suffered at the hands of Savile. To make matters worse, his considerable fame has been replaced by a burgeoning notoriety. This is reminiscent of the damnatio memoriae that befell Geta and his sister-in-law Plautilla. The marble inscription that once carried their name is a “highlight” of the British Museum precisely because of the dark deeds associated with them and the futile efforts made to delete them from history. In their case, damnatio memoriae has, in a perverse way, enhanced their posthumous status centuries after their grisly deaths. Let’s hope that the same will not be said of the late Jimmy Savile – an individual who has gone from saint to scoundrel in the space of just a few short months. ___ Notes (1) “Marble inscription with damnatio memoriae of Geta, son of Septimius Severus” (Roman, AD 193-211, from Rome, Italy, height 81.5 cm, width 47.5 cm, British Museum, Townley Collection, GR 1805.7-3.210, http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/gr/m/marble_inscription.aspx). (2) Martin Beckford, “Sir Jimmy Savile was a ‘predatory sex offender’, police say”, The Daily Telegraph, 09/10/2012, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/9597158/Sir-Jimmy-Savile-was-a-predatory-sex-offender-police-say.html. (3) “Jimmy Savile’s headstone removed from Scarborough cemetery” and “Sir Jimmy Savile Scarborough footpath sign removed”, BBC News, 12/10 & 08/10/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-19893373 and www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-19867893.  Hillsborough: The Report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel has just been published. This 400-page document investigates an incident which occurred on 15th April 1989 at the Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield. On that awful day a soccer match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest had to be abandoned when the Leppings Lane stand became overcrowded. The ensuing crush led to the death of 96 Liverpool football fans. This terrible loss of life and the unbearable grief of their loved ones have been compounded over the past 23 years by a deliberate and systematic attempt to cover up what happened. That much is clear from the report released today. One of its most startling findings relates to the fact that written statements made at the time by police officers and members of the South Yorkshire Metropolitan Ambulance Service were altered. Why? The answer is emphatic: “Some 116 of the 164 [police] statements identified for substantive amendment were amended to remove or alter comments unfavourable to SYP [South Yorkshire Police].”(1) In other words, our supposed custodians of law and order – both then and since – have been more interested in their own image and reputation than in finding out what went so catastrophically wrong. And this, I argue, is why a so-called “academic” subject such as History is so vital to a democratic and viable society. Compare the contemporary example set out above with this quotation from The Historian’s Craft by Marc Bloch: One of the most difficult tasks of the historian is that of assembling those documents which he [or she] considers necessary... Despite what the beginners sometimes seem to imagine, documents do not suddenly materialize, in one place or another, as if by some mysterious decree of the gods. Their presence or absence in the depths of this archive or that library are due to human causes which by no means elude analysis. The problems posed by their transmission, far from having importance only for the technical experts, are most intimately connected with the life of the past, for what is at stake is nothing less than the passing down of memory from one generation to another. Bloch had no need to restrict his attention to “the life of the past”. Because “the passing down of memory from one generation to another” occurs in the here and now. The Hillsborough disaster is history. But its living legacies are life, truth and justice in the present. These qualities should be our memorial to ten-year-old Jon-Paul Gilhooley who, together with 95 fellow supporters, became the innocent victim of official incompetence, misconduct and suppression on that fateful day in April 1989. ____ Notes (1) Hillsborough: The Report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel, September 2012, HC 581, London: The Stationery Office, p. 339. (2) Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004, pp. 57-59. “The places that we have known belong now only to the little world of space

on which we map them for our own convenience. None of them was ever more than a thin slice, held between the contiguous impressions that composed our life at that time; remembrance of a particular form is but regret for a particular moment; and houses, roads, avenues are as fugitive, alas, as the years.” Marcel Proust, Remembrance of Things Past, Volume I, translated by Charles Kenneth Scott-Moncrieff After writing Manipulating Moderna Museet, I decided to revisit the museum for one last look at "Image over Image" – a temporary exhibition devoted to the work of Elaine Sturtevant. This decision was in itself noteworthy. In one of the gallery spaces it’s possible to watch a video of “The Powerful Pull of Simulacra”. This is the title of the lecture Sturtevant gave in conjunction with the show.(1) In it she argues that “objects are out; image is the power”. But if this is the case, why do we need a museum of objects such as Moderna Museet? Indeed, what is the point of making a physical pilgrimage to see “Image over Image”? The answer, I think, is all to do with “the powerful pull of simulacra”. I paid a repeat visit to “Image over Image” in order to savour being in the presence of what might be termed “genuine fakes”. This is a reference to one of the most striking moments of Sturtevant’s lecture: the part when she talks about “falsity presented as truth”. That evocative phrase – “falsity presented as truth” – encapsulates “Image over Image”.  My moment of epiphany came as I genuflected in a room containing four works entitled Warhol Flowers. These are all dated 1990 – the same year of creation as those Brillo boxes that Pontus Hultén so very generously donated to Moderna Museet. And then it struck me! Moderna Museet is a secular temple. Its sacred spaces and canonical texts authenticate that which it displays. Sturtevant’s “Image over Image” has allowed Moderna Museet to reclaim Pontus Hultén’s “fake” Brillo boxes. This in turn expunges their questionable provenance which threatened to besmirch the good name of Moderna Museet’s most illustrious leader. Thanks to Sturtevant, it is now possible for the Brillo boxes’ falsity to be presented as truth. For is it not the case that, at the very same time that Sturtevant was propagating Warhol Flowers, Hultén was conjuring up a whole new suite of Brillo boxes? Endorsing the former has the effect of validating the latter. And that’s how dead artist’s can produce genuine works of art long after their deaths. If you still don’t get it, well, that’s probably just your “determination to be stupid” – to quote that true original, Elaine Sturtevant.(2) ___ Note (1) Elaine Sturtevant, “The Powerful Pull of Simulacra”, a talk given at the symposium, Beyond Cynicism: Political Forms of Opposition, Protest, and Provocation in Art, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 18th March 2012. (2) Ibid. Images to accompany my recent exhibition review of Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery in the county of Kent (Museums Journal, Issue 112 (05), pp. 54-57).

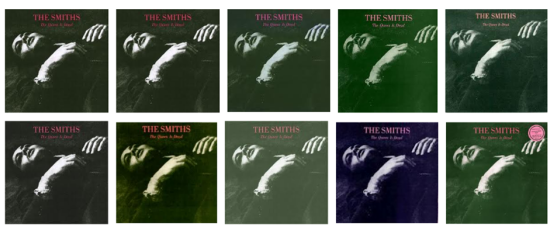

The museum is rightly grateful to that most capacious of collectors, Julius Brenchley (1816-73). This hoarder has been mentioned in an earlier blog posting, which also alluded to the bedroom antics of Maidstone Museum’s former curator, William Lightfoot. See “Brenchley's bedroom benefaction”. The weather in Stockholm today is terrible. This is precisely the sort of thing that kills me. What happens whenever I feel like going for a nice walk where it’s quiet and dry? The rain pours down and flattens my hair, that’s what. I wonder what it’s like back in dear old Blighty? On second thoughts, I don’t really care: I’ve said farewell to that particular land’s cheerless marshes. I swear it’s the last time I sit on a delayed, overcrowded train stuck among the railway arches somewhere between London, Liverpool, Leeds or Birmingham. There’s nothing worse than being hemmed in like a boar. Even so, I’d still like to go back now and then to chat about precious things. But, really, the things you read in the British newspapers! All those jeremy hunts spouting inane rubbish about love, law and poverty. Perhaps it’s just me, but don’t the way things are going make you wonder if the world has changed? I don’t trust anyone these days, not with all the lies they make up. True, people don’t have long hair any more. And all the pubs have shut down together with the churches. But the liars are still at large: everyone’s out to snatch your money or wreck your body. God, my limbs ache. And it feels so lonely, despite being hemmed in by so many bores. And the media doesn’t help either. I read about a gang of kids peddling drugs. Honest to God, I never even knew what drugs were at their age. I was too tied to my mother’s apron strings to worry about incarceration, castration or coronations. Actually, that reminds me of one bright spot to brighten up Blighty’s cheerless marshes. Did you see that picture on the front of the other day’s Daily Mail? I know she only suffered mild concussion, but it was a really wonderful thing to see her royal lowness all bandaged up and with her head in a sling. I wonder what Charles thought when he saw it? He’d probably liked to have been the monarch on the front cover, veiled in some regalia nicked from his mum. Why is it that he of all people should be next in line for regality? I bet if the libraries or archives were still open any one of us could find some historical facts to prove that they are a pale descendent of some old queen from eighteen generations back. No-one cares of course. Especially not those flag-waving patriots hemmed in like boars along their rain-soaked street parties that stretch from London to Liverpool, Leeds to Birmingham. Honestly, the only way to get them to listen would be to break into Buckingham Palace armed with just a rusty spanner hidden inside a sponge. Sneaking past Charles wouldn’t be difficult: he’d be too busy struggling into his mater’s bridal veil and practicing his coronation steps to notice me flit past. And I bet his mother would confuse me for someone else: “Eh, I know you”, she’d rasp, “and you cannot sing”. “That’s nothing”, I’d reply whilst prising my corroded tool from its soft wrapping: “you should hear me play piano”. This won’t happen, of course. It’s raining too hard for me to venture out. So I may as well stay here where it’s quiet and dry. Perhaps I’ll take a surreptitious peek at the Daily Mail online. Oh, look! It says here that the queen has just taken a nasty tumble... Morrissey/Marr (with Mills, Godfrey & Scott)

“The Queen Is Dead (Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty)” The Queen is Dead, Rough Trade / Sire, 1986, 6:24  “[A] rich mixture of foreign influences has entered our homes for centuries and continues to do so today.” So says the introductory panel to the exhibition “At Home With the World”. This is the title of the Geffrye Museum’s contribution to the laughably labelled “Cultural Olympiad”. The temporary display seeks to explore notions of Englishness in the domestic sphere. What – if anything – is nationally distinct about the homes of England given the ongoing patterns of “foreign influence” that pervade our public and private spaces? This question resonates with a line of dialogue from a play that I am going to see later this evening just up the road from the Geffrye Museum: “All I want is the England I used to know... When you knew where you were and all the houses had gardens and old ladies could feel safe in the street at night.” This understandable nostalgia is ratcheted into a gleefully xenophobic rant by a mild mannered man who goes by the name of Martin Taylor. He must surely be the most compelling and controversial character conjured up by the playwright, Dennis Potter. His play, Brimstone and Treacle charts how monstrous Martin wheedles his way into the moribund home of the Bates family. Tensions between the unhappily married Mr and Mrs Bates are exacerbated by the condition of their tragic daughter, Pattie. She lays bedridden and brain damaged following a traffic accident. Martin decides to quite literally lend a hand. The nature of his grotesque physical intervention led to the censorship of Potter’s Brimstone and Treacle. Potter wrote his television play for the BBC some four decades ago. Time, however, has not diminished the shocking denouement of the drama. So it is with a growing sense of guilty excitement that I sit in the sun-drenched café of the Geffrye Museum writing these words and waiting impatiently for the drama to unfold. Until now I have only ever seen Potter’s work through the mollifying medium of television. The chance to come within touching distance of Dennis’ devilishly disturbing world has brought me to London and the Arcola Theatre in Hackney. As luck would have it, the last leg of my journey to the theatre involved the number 149 double-decker bus from London Bridge station. It strikes me that the loathsome Norwegian terrorist, Anders Behring Breivik should be compelled to serve out his life sentence on this bus route. He’d be driven out of his miniscule mind by the glorious microcosm of London life that is played out by a worldwide cast of bus passengers, 24-hours a day. If it were not for the number 149 I wouldn’t have passed by the Geffrye Museum. This marvellous museum has provided the ideal preparation for Brimstone and Treacle. As a “museum of English homes and gardens”, it is filled with stage-set interiors charting a chronological sweep through English domestic history. The Bates’ morose middle class abode of the mid-1970s would fit in beautifully as one of the room sets of the Geffrye Museum. These museumified interiors confirm our collective obsession with “home”. Many people share the sentiments of Mr Bates: they long for a private refuge from the world flanked by a neat little garden and a street outside filled with safe-and-sound old ladies. Of course, these exact same private paradises are all too often the setting for all manner of barbarisms perpetrated by “sweet talking rapists at home”.(1) The domestic sphere is, then, a potent mixture of brimstone and treacle. Dennis Potter makes this shockingly apparent in his brilliant play of that title. I really hope that the Arcola Theatre does justice to Potter’s helping of demonic hospitality. ___ Note (1) The Blow Monkeys, “Sweet Talking Rapist at Home”, Whoops! There Goes the Neighbourhood, 1989, RCA. (After) Brett Murray's "The Spear"

See "Jacob Zuma painting vandalised in South Africa gallery" BBC News, 22/05/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-18159204 |

Para, jämsides med.

En annan sort. Dénis Lindbohm, Bevingaren, 1980: 90 Even a parasite like me should be permitted to feed at the banquet of knowledge

I once posted comments as Bevingaren at guardian.co.uk

Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

_

Note All parasitoids are parasites, but not all parasites are parasitoids Parasitoid "A parasite that always ultimately destroys its host" (Oxford English Dictionary) I live off you

And you live off me And the whole world Lives off everybody See we gotta be exploited By somebody, by somebody, by somebody X-Ray Spex <I live off you> Germ Free Adolescents 1978 From symbiosis

to parasitism is a short step. The word is now a virus. William Burroughs

<operation rewrite> |