Answer A dumping ground for "all kinds of cultural litter".*

* Le Guin, Ursula K. (1971/2001) The Lathe of Heaven (London: Orion), p. 152.

|

Question What is a museum?

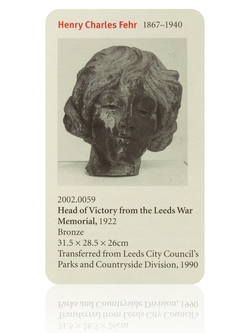

Answer A dumping ground for "all kinds of cultural litter".* * Le Guin, Ursula K. (1971/2001) The Lathe of Heaven (London: Orion), p. 152.  Next month the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds will open an exhibition entitled, "United Enemies". It aims to explore "the problem of sculpture in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s". The slogan emblazoned on the institute's facade resonates with the war memorial outside. One of the allegorical groups at its base features a sculpture of St George conquering the dragon. The saint and the serpent are "united enemies" – frozen forever in a brutal bronze embrace and "symbolical... of the everlasting struggle between good and evil."(1) But all is not as it seems. The Carrara marble obelisk, plinth and steps were executed by Carlo Domenico Magnoni (c.1871-1961). Henry Charles Fehr (1867-1940) was responsible for the bronze sculptures. The ensemble once stood in the City Square just outside the main railway station. Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood unveiled it there in 1922.(2) Fifteen years later it was shifted to Victoria Gardens on The Headrow, where it still stands. Originally Fehr's "Winged Victory" hovered triumphantly over St George. This was removed in 1967. Since 1991 the more pacific "Angel of Peace" by Ian Jubb (born 1947) has surmounted the dragon slayer. This chimes with Fehr's allegory of "Peace" which, like St George, stands at the base of the obelisk.(3) So, whilst this memorial looks fixed and unchanging, appearances can be deceptive. The Leeds War Memorial does all it can to convince us that it speaks for everyone, forever - a truly public pronouncement. The patina of time adds to its nostalgic allure. But compare present-day attitudes with this newspaper article published in 1922: After something like three years of procrastination, mainly due to a lack of monetary support, the Leeds War Memorial has become an accomplished fact with the fixing of the date for the unveiling ceremony, which will be on October 14. The project has been attended by criticism and scarcely-veiled hostility since its inception. By the time Sir Reginald Blomfield's plans had been provisionally accepted by the War Memorial Committee most of the parishes and districts had their individual memorials, either erected or in hand. No doubt this was one of the reasons the subscription-list for the fund of £70,000 never reached £7,000; others lay in objections to the memorial design; in objections to the Cookridge Street site; in a contention more than once urged that a war memorial ought to afford benefit to the living disabled, for instance, rather than a memorialising of the dead; and also in the unemployment and distress then becoming acute.(4) The temporary carpet of poppies at the feet of St George; the metamorphosis from victory to peace; and a knowledge of the memorial's deeply contested origins remind us that objects are forever being "perceived and uttered in different ways".(5) A monument's meaning is not stable but is instead "in suspense... and... indeterminate". The Leeds memorial has at various points in its history attracted suffragists, pacifists, war veterans and fairtraders.(6) Its potential significance, it seems, is infinitely malleable. A commemorative memorial such as this is thus "tailored to the needs of the present... and especially the future". Those that gather at symbols of remembrance do so in an effort "to determine, delimit and define the always open meaning of the present." Objects are, in short, subject to all manner of "cognitive 'filling-in' strategies". One such "cognitive 'filling-in' strategy" is this very blog posting. I began writing it on the eve of my talk to delegates of the "Sculpture and Comic Art" conference taking place in the art gallery directly behind St George and his foe. My talk uses the ideas of Pierre Bourdieu to explore Estonia's Bronze Soldier. This Soviet-era war memorial is simultaneously interpreted as a symbol of liberation and occupation. Opposing camps have clashed at the foot of the statue in a futile effort "to determine, delimit and define the always open meaning of the present." In April 2007 a riot erupted on the streets of Tallinn when the authorities moved the monument from the city centre to a military cemetery. The Bronze Soldier obliged these "united enemies" to realise an uncomfortable truth, namely that objects are "perceived and uttered in different ways". If you're in any doubt about this, just ask the poor old "Winged Victory". After her removal from the Leeds war memorial she was, like Estonia's Bronze Soldier, moved to a burial place, namely Cottingley Crematorium. However, in 1988 the metal maiden was deemed to be in such a poor state of repair that she was melted down. The only part that escaped this authorised vandalism was the head. It is now in the collections of Leeds City Art Gallery. This decapitated angel of victory looks anything but victorious. What better example could there be of the indeterminacy of meaning and of an object's infinite capacity for being "perceived and uttered in different ways"? And who knows, perhaps one day St George will also be sent back to the furnace from whence he came? He and the dragon would cease to be "united enemies". The severed serpent might then be set free to embark on an exciting new life full of unanticipated meanings...  ____ Notes (1) Unveiling of the War Memorial by the Right Hon. Viscount Lascelles K.G., D.S.O. Saturday, 14th October, 1922, at 3:30 (Leeds: Jowett & Sowry), p.2. (2) The Yorkshire Evening News felt it was "appropriate the Viscount Lascelles should perform the duty, as he [had] a distinguished war record and was thrice wounded while serving on the Western front." (6/10/1922). (3) Information about the monument is derived from interpretation panels in the sculpture galleries of Leeds City Art Gallery (15/11/2011). (4) "The Leeds War Memorial", The Yorkshire Observer, 6/10/1922. (5) This and all subsequent quotations are derived from Pierre Bourdieu's "The Social Space and the Genesis of Groups", Theory and Society, Vol. 14, No. 6, 1985, pp. 723-744 (p. 728). (6) See http://www.visitleeds.co.uk/thedms.aspx?dms=13&feature=1&venue=2193653. The sound of silence...  Sevenoaks Cottage Hospital "Today We Remember Martin Luther King – Tomorrow We Don't" The quotation above doesn't come from some highbrow History book or academic article exploring collective memory. Instead it's from a newspaper. The New York Times, perhaps? Or the Sydney Herald? No, the actual source was The Springfield Shopper.(1) Homer Simpson's local paper is an odd place to study history. Yet this fleeting, one-line gag in The Simpsons is in fact a witty and perceptive appreciation of how societies remember and forget. The annals of past events are limitless. This gives rise to whole calendars of commemorations – like Martin Luther King Day. An event such as this is one of the mechanisms necessary to filter, rank and arrange the past; to make it manageable and to put it to use. To turn the past into History. Anniversaries help supply the present with their historical fix. No matter how insatiable we are, there is always a ready supply of past pleasures and pains for us to use and abuse. One anniversary leads to another and another in a bulimic spewing up of the past.(2) And by comparing multiple commemorations of the same event we get an insight into the ways in which the past is put into the service of the present.(3) Take today, for example. It is Armistice Day. Ninety-three years have passed since the end of the "Great War". This gives rise to the intoning of that familiar mantra: On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the guns fell silent and the First World War came to an end. Today on 11th November, we remember, in silence, all those who have given their lives in war in the cause of peace and freedom.(4) This moment is marked by repetition. The observing of silences; the laying of wreaths; the tolling of bells; the playing of music. These recurring performances have been re-enacted following a score set down by the Royal British Legion exactly 90 years ago. Such rituals are intended to interrupt the haphazard unfolding of day-to-day events by inserting a familiar pause – a link in time connecting our present with our past, secure in the knowledge that this will happen again in our future. This is how the chain of history is constructed. Shared memory is deployed to forge collectivities. Repetition and sameness are emphasised. But, if we look carefully, what they actually highlight is that which is different or new. Thus, whilst we are remembering past wars, we are also encouraged to reflect on current conflicts. Those that observe silences or gather around memorials in the UK are made aware that British soldiers in Afghanistan are doing just what their forebears did, namely giving "their lives in war in the cause of peace and freedom." Not everyone agrees with this, of course. Certain members of the now-illegal "Muslims Against Crusades" were planning a counter demonstration today. They too wished to observe this memorial occasion and its associated symbolism. Yet they would prefer to burn a plastic poppy rather than place it at the foot of an old war memorial. Such behaviour is distasteful and disrespectful – but should it be punishable by imprisonment? The potency of the poppy confirms the sense in which 'the flower has become an iconic symbol of remembrance and sacrifice.'(5) Its importance and that of the November ritual as a whole appears to be increasing rather than diminishing as the years go by. This explains the seemingly disproportionate amount of attention the media devotes to reports of a war memorial being vandalised or dishonoured. A steadily rising number of plaques listing the names of the dead have been stolen from such monuments. The high value of scrap metal makes an uncomfortable parallel with the high value of the sacrifice inscribed in each and every liquefied name. The heat required to melt these metal sheets is matched by the temperature rising in commemorative terms. This is due to the imminent arrival of the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. Will 2014 represent a high-water mark of remembrance? We can't know the answer to this because we simply don't know what the future holds or what future generations will choose to remember and forget. So it seems fair to say that The Springfield Shopper headline got it right and wrong: "Today We Remember Armistice Day – Tomorrow We Don't". But the day after that we will: it's Remembrance Sunday. And the wreath-laying rituals will be repeated all over again – for some people at least. _____ Notes (1) 'The Springfield Shopper', The Simpsons 18/9 (2006). (2) Pierre Nora, Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past. Vol. III: Symbols, New York, Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 609. (3) Stuart Burch, 'The Texture of Heritage: A Reading of the 750th Anniversary of Stockholm', International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 11 (3), 2005, pp. 211-233. (4) BBC Radio 4 News, 11:00, 11/11/2011. (5) Angus Crawford, The World at One, BBC Radio 4, 11/11/2011. __________ Supplemental 18/11/2011 One American citizen who does not observe Martin Luther King Day is George Orr, the principal protagonist in Ursula K. Le Guin's superb book, The Lathe of Heaven (1971). He is able to alter the world by having what he terms "effective" dreams (p.13). Orr's unconscious solution to racism is to dream into existence a globe populated solely by grey-skinned people. But in so doing he erases the woman he loves: Heather Lelache's "color of brown was an essential part of her, not an accident... She could not exist in the gray (sic) people's world. She had not been born." (p. 129) And that is not all: this is also now a world that "found in it no address that had been delivered on a battlefield in Gettysburg, nor any man known to history named Martin Luther King." (p. 129) All this might seem like "a small price to pay for the complete retroactive abolition of racial prejudice". But George Orr finds the situation "intolerable. That every soul on earth should have a body the color of a battleship: no!" (p. 129). Source: Le Guin, Ursula K. (1971/2001) The Lathe of Heaven (London: Orion) |

Para, jämsides med.

En annan sort. Dénis Lindbohm, Bevingaren, 1980: 90 Even a parasite like me should be permitted to feed at the banquet of knowledge

I once posted comments as Bevingaren at guardian.co.uk

Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

_

Note All parasitoids are parasites, but not all parasites are parasitoids Parasitoid "A parasite that always ultimately destroys its host" (Oxford English Dictionary) I live off you

And you live off me And the whole world Lives off everybody See we gotta be exploited By somebody, by somebody, by somebody X-Ray Spex <I live off you> Germ Free Adolescents 1978 From symbiosis

to parasitism is a short step. The word is now a virus. William Burroughs

<operation rewrite> |