The slogan emblazoned on the institute's facade resonates with the war memorial outside. One of the allegorical groups at its base features a sculpture of St George conquering the dragon. The saint and the serpent are "united enemies" – frozen forever in a brutal bronze embrace and "symbolical... of the everlasting struggle between good and evil."(1)

But all is not as it seems. The Carrara marble obelisk, plinth and steps were executed by Carlo Domenico Magnoni (c.1871-1961). Henry Charles Fehr (1867-1940) was responsible for the bronze sculptures. The ensemble once stood in the City Square just outside the main railway station. Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood unveiled it there in 1922.(2) Fifteen years later it was shifted to Victoria Gardens on The Headrow, where it still stands. Originally Fehr's "Winged Victory" hovered triumphantly over St George. This was removed in 1967. Since 1991 the more pacific "Angel of Peace" by Ian Jubb (born 1947) has surmounted the dragon slayer. This chimes with Fehr's allegory of "Peace" which, like St George, stands at the base of the obelisk.(3)

So, whilst this memorial looks fixed and unchanging, appearances can be deceptive. The Leeds War Memorial does all it can to convince us that it speaks for everyone, forever - a truly public pronouncement. The patina of time adds to its nostalgic allure. But compare present-day attitudes with this newspaper article published in 1922:

After something like three years of procrastination, mainly due to a lack of

monetary support, the Leeds War Memorial has become an accomplished

fact with the fixing of the date for the unveiling ceremony, which will be on

October 14. The project has been attended by criticism and scarcely-veiled

hostility since its inception. By the time Sir Reginald Blomfield's plans had

been provisionally accepted by the War Memorial Committee most of the

parishes and districts had their individual memorials, either erected or in

hand. No doubt this was one of the reasons the subscription-list for the fund

of £70,000 never reached £7,000; others lay in objections to the memorial

design; in objections to the Cookridge Street site; in a contention more than

once urged that a war memorial ought to afford benefit to the living disabled,

for instance, rather than a memorialising of the dead; and also in the

unemployment and distress then becoming acute.(4)

The temporary carpet of poppies at the feet of St George; the metamorphosis from victory to peace; and a knowledge of the memorial's deeply contested origins remind us that objects are forever being "perceived and uttered in different ways".(5) A monument's meaning is not stable but is instead "in suspense... and... indeterminate". The Leeds memorial has at various points in its history attracted suffragists, pacifists, war veterans and fairtraders.(6) Its potential significance, it seems, is infinitely malleable. A commemorative memorial such as this is thus "tailored to the needs of the present... and especially the future". Those that gather at symbols of remembrance do so in an effort "to determine, delimit and define the always open meaning of the present." Objects are, in short, subject to all manner of "cognitive 'filling-in' strategies".

One such "cognitive 'filling-in' strategy" is this very blog posting. I began writing it on the eve of my talk to delegates of the "Sculpture and Comic Art" conference taking place in the art gallery directly behind St George and his foe. My talk uses the ideas of Pierre Bourdieu to explore Estonia's Bronze Soldier. This Soviet-era war memorial is simultaneously interpreted as a symbol of liberation and occupation. Opposing camps have clashed at the foot of the statue in a futile effort "to determine, delimit and define the always open meaning of the present." In April 2007 a riot erupted on the streets of Tallinn when the authorities moved the monument from the city centre to a military cemetery. The Bronze Soldier obliged these "united enemies" to realise an uncomfortable truth, namely that objects are "perceived and uttered in different ways".

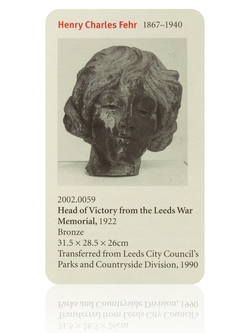

If you're in any doubt about this, just ask the poor old "Winged Victory". After her removal from the Leeds war memorial she was, like Estonia's Bronze Soldier, moved to a burial place, namely Cottingley Crematorium. However, in 1988 the metal maiden was deemed to be in such a poor state of repair that she was melted down. The only part that escaped this authorised vandalism was the head. It is now in the collections of Leeds City Art Gallery. This decapitated angel of victory looks anything but victorious. What better example could there be of the indeterminacy of meaning and of an object's infinite capacity for being "perceived and uttered in different ways"?

And who knows, perhaps one day St George will also be sent back to the furnace from whence he came? He and the dragon would cease to be "united enemies". The severed serpent might then be set free to embark on an exciting new life full of unanticipated meanings...

Notes

(1) Unveiling of the War Memorial by the Right Hon. Viscount Lascelles K.G., D.S.O. Saturday, 14th October, 1922, at 3:30 (Leeds: Jowett & Sowry), p.2.

(2) The Yorkshire Evening News felt it was "appropriate the Viscount Lascelles should perform the duty, as he [had] a distinguished war record and was thrice wounded while serving on the Western front." (6/10/1922).

(3) Information about the monument is derived from interpretation panels in the sculpture galleries of Leeds City Art Gallery (15/11/2011).

(4) "The Leeds War Memorial", The Yorkshire Observer, 6/10/1922.

(5) This and all subsequent quotations are derived from Pierre Bourdieu's "The Social Space and the Genesis of Groups", Theory and Society, Vol. 14, No. 6, 1985, pp. 723-744 (p. 728).

(6) See http://www.visitleeds.co.uk/thedms.aspx?dms=13&feature=1&venue=2193653.