| Thank goodness for radio. The BBC drama I've just heard was so brilliant that it inspired me to revive this undead blog. Louise Monaghan's one-off play is entitled, The Man Inside the Radio Is My Dad. It is inspired by Storybook Dads - a charity that works to help prisoners stay in contact with their families. It's funny, touching and uplifting with superb performances by the three female protagonists - Chloe, her mum and her nan. Nan's favourite television programme is called "Pointless". This play for voices is anything but. |

|

So click here. Stop looking. Start listening. (Tip: have a tissue handy.)

Margaret Thatcher has passed into history.

How should she be remembered? Through her encounter with Diana Gould (1926-2011). Mrs Gould exposed the real Margaret Thatcher. Belligerent, disdainful, hectoring, bullying, intransigent. All things that should be consigned to history. “Where there is discord, may we bring harmony...”

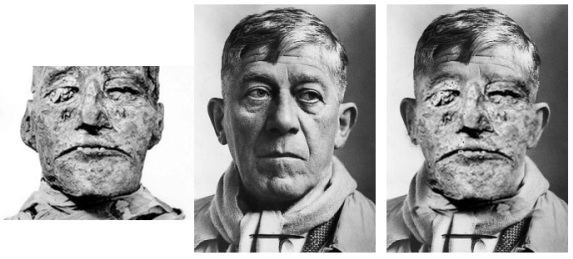

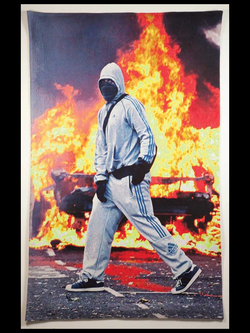

These words of St. Francis of Assisi were cited by Margaret Thatcher on the steps of Number 10 Downing Street on Friday 4th May 1979 – the day she took office as the first female prime minister of Great Britain. Mrs Thatcher went on to add some thoughts of her own: “and to all the British people – howsoever they voted – may I say this. Now that the Election is over, may we get together and strive to serve and strengthen the country of which we’re so proud to be a part.”(1) This is indicative of a paradox that runs right through Thatcher’s long and eventful period in power. Those who laud her achievements urge her detractors to accept that, whilst they might not have agreed with her politics, she should be admired as a great patriot with a “lion-hearted love for this country”. That was how David Cameron characterised her on the day she died. He chose to deliver his eulogy on the spot from where his predecessor addressed the media back in 1979. Nevertheless, at the same time as praising the person he regarded as “saving” the country, Cameron added: “We can’t deny that Lady Thatcher divided opinion.” He insisted, however, that Thatcher “has her well-earned place in history and the enduring respect and gratitude of the British people.”(2) It is characteristic of Mr Cameron that he should deliver such a contradictory statement. If Thatcher “divided opinion” how can “the British people” be of one mind? And if she loved Britain so much, how could Thatcher encourage a climate in which some Britons prospered and thrived at the expense of others? This continues to pose a problem now that she is dead. How should she be memorialised? Bear in mind that a statue erected in her lifetime has already been decapitated by an irate “patriot”.(3) An early opportunity to test the public mood will come during the ceremony leading to her cremation. Whilst she will not be given a state funeral, she will be accorded a military procession to St Paul’s Cathedral. During that parade all manner of socialists, former miners, Irish nationalists, Argentines, anti-Apartheid veterans, LGBT campaigners and others might seek to pay their final respects in ways that will subvert David Cameron’s confident assertion regarding Thatcher’s “place in history and the enduring respect and gratitude of the British people.” Once the funeral is over thoughts will turn to a more permanent commemoration. At that point the Iron Lady will be transmogrified into bronze. The obvious place to site such a memorial is Parliament Square.(5) There she can surmount a pedestal alongside the petrified Churchill and generate an interesting dialogue with the statues of two South Africans, Jan Smuts and Nelson Mandela. Thatcher’s opposition to international sanctions against Apartheid South Africa – plus her hostility to German reunification – are reminders that differences of opinion over her legacy are not confined to England, Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland. In each of these areas one can cite a litany of issues that remain contentious today, from the North-South divide in England to the piloting of the Poll Tax in Scotland, the decimation of the industrial communities of South Wales and her administration’s secret negotiations with the IRA in stark contrast to Thatcher’s publicly stated position. It seems inevitable that an official memorial to Lady Thatcher will be erected in the not-too-distant future. All too often such commemorations pretend to be natural occurrences that are universally supported. That lie will be impossible to sustain in this particular instance. A literal Iron Lady will confirm an observation made by Kirk Savage: “Public monuments do not arise as if by natural law to celebrate the deserving; they are built by people with sufficient power to marshal (or impose) public consent to their erection.”(4) Waves of attacks will be unleashed on any tangible memorial to Thatcher. These will be dismissed as vandalism or accepted as iconoclasm depending on one’s point of view. But the daubs of paint or attempts at decapitation will confirm one thing. Mrs Thatcher achieved much, but by her own measure she failed in at least one regard. She came to office urging Britons to “get together” and help her “bring harmony”. Yet her enduring legacy is division and discord. And that’s something that even David Cameron cannot deny. ----- Notes (1) Margaret Thatcher, “Remarks on becoming Prime Minister (St Francis’s prayer)”, 04/05/1979, http://www.margaretthatcher.org/speeches/displaydocument.asp?docid=104078 (2) Steven Swinford & James Kirkup, “Margaret Thatcher: Iron Lady who made a nation on its knees stand tall”, Daily Telegraph, 08/04/2013, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/margaret-thatcher/9980285/Margaret-Thatcher-Iron-Lady-who-made-a-nation-on-its-knees-stand-tall.html (3) The perpetrator was Paul Kelleher, a thirty-seven year old theatre producer. His justified his actions by claiming that the attack was in protest against global capitalism. See Stuart Burch, On Stage at the Theatre of State: The Monuments and Memorials in Parliament Square, London (A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, March 2003), pp. 350-351. (4) Kirk Savage, “The politics of memory: Black emancipation and the Civil War monument”, in John R Gillis (ed.), Commemorations: the politics of national identity, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 135. (5) This was something that I called for a decade ago: “An image of Margaret Thatcher in the sacred yet so vulnerable domain of Parliament Square would infuse it with ‘living power’. For the statue, taking its rightful place alongside Churchill, would be finely posited between veneration and disdain and then, in the fullness of time, between neglect and ignorance.” Burch, On Stage at the Theatre of State, 2003, p. 351.  Marc Quinn, The Creation of History (2012) Marc Quinn, The Creation of History (2012) On Thursday 4th August 2011 officers of the Metropolitan Police Service stopped a taxi on Ferry Lane in Tottenham Hale, London. Its occupant – Mark Duggan – was subsequently shot dead in uncertain circumstances. This single incident gave rise to a spate of riots across England. The worst scenes took place in the capital. A defining image of that summer of violence is a photograph taken by the Turkish born photojournalist, Kerim Okten. It shows a man in a grey tracksuit and trainers. The skin on his hands is covered by black gloves. His face is veiled by a mask such that only his eyes are visible: they gaze fixedly at the camera lens. Framing that stare are the orange flames and choking black smoke of a burning vehicle. Various versions of this iconic scene are available online. They differ in all sorts of major and minor ways. Some depict the main protagonist in alternative poses; others show bystanders looking on at the searing shell of the car. Text invariably accompanies the picture wherever it appears. A front page headline such as “The battle for London” turns this masked celebrity into a capital warrior. Replace that caption with something like “Yob rule” and our battle-scarred warrior becomes a mindless hoodlum. His slow, purposeful steps and cold stare do indeed make this lord of misrule appear above the law. The rights to Okten’s image have now been acquired by the British artist Marc Quinn. He has used it as the inspiration for a variety of artworks including paintings, a sculpture and even a tapestry. The latter has been entitled The Creation of History (2012) and exists in an edition of five. The title chose by Quinn reflects his belief that the 2011 riots constitute “a piece of contemporary history”. The artist is quick to add, however, that this history – like every past event – is “a complex story and raises as many questions as it [does] answers. Is this man a politically motivated rioter? A looter? What is in his pocket? And rucksack? More intriguingly, the mask he wears appears to be police-issue: could he even be a policeman?”(1) The merest suggestion that our photogenic “yob” might in fact be a lawgiver rather than a lawbreaker disturbs this already troubling image, transforming it before our very eyes. This is exacerbated further in Quinn’s tapestry transmutation. Metamorphosing the pixels of a digital photo into the knots of a woven image catapults this contemporary history back in time. Now our “yob” can stand alongside armour-suited warriors in a medieval pageant. The rich heritage of Quinn’s The Creation of History makes it worthy to enter into the sacred realm of the museum. And what better institution than Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery? This establishment rose like a phoenix from the flames of a riot: on 10th October 1831 a group of rabble-rousers intent on creating a little history of their own torched the palatial home of the Duke of Newcastle in protest at his opposition to electoral reform. For fifty years the burnt out shell of the building remained an admonitory reminder of this bad behaviour. Then, in the 1870s, it was converted into the first municipally funded museum outside of London. This place of learning and leisure still stands. And it only exists thanks to the sort of scenes that were to take place 180 years later – not only in London but also Nottingham, where Canning Circus police station was firebombed by tracksuited warriors / yobs. So, with this in mind, wouldn’t it make perfect sense for the curators at Nottingham Castle Museum to acquire one of the five editions of Marc Quinn’s The Creation of History? It could hang on the same walls that were once covered by tapestries – before “yob rule” led to them being unceremoniously ripped down and either burnt or “sold to bystanders at three shillings per yard.”(2) ___ Notes (1) Cited in Gareth Harris, “London riots get tied up in knots”, The Art Newspaper, Iss. 243, 07/02/2013, accessed 08/02/2013 at http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/quinn-tapestry/28545. (2) Harry Gill, A Short History of Nottingham Castle (1904), available at, http://www.nottshistory.org.uk/gill1904/reformbill.htm._  Screencap from Life in a Day Over the weekend I spent more hours than is healthy at Birmingham Airport. The reason for my enforced stay was Britain’s inability to cope with a bit of ice and snow. To pass the time I decided to overdose on coffee and, with too much caffeine in my bloodstream and a lack of real spice in my life, I reached for my Sony eReader. The story I chose to read seemed appropriate given my plight: The Machine Stopped by E.M. Forster (1879-1970). Written in 1909 this novella is scarily prescient. It concerns an imaginary future in which the human race lives underground and eschews direct contact with the outside world. To achieve this it has constructed The Machine. This networked intelligence tends to the human race’s every need, be it physical, intellectual or spiritual. As a result, the thought of leaving the glorious isolation of one’s artificial cocoon is an anathema. Natural air, daylight, direct human contact – all are nauseating to people conditioned to living their lives sat on a chair, staring into a monitor and waiting for their virtual friends to message them with an original idea. Don’t forget, all this was written over a century ago. I am now back at home, safe and sound after my Birmingham exile. And what am I doing? Well, I’m sat in a chair, staring at a monitor, of course. Meanwhile life is probably still going on outside. One thing of which I am certain is that the world existed on Saturday 24 July 2010. I know this because I’ve just watched the film “Life in a Day”. It’s a 94 minute edited compilation of 80,000 YouTube clips all recorded on a single day in July a few years ago. One of the best bits of the film is the sequence that features Angolan women chanting as they work. I am clearly not alone in this view. A YouTube user by the name of Pellentior has uploaded the music. While listening I scrolled down to the comments, where I found the following post by “cherryblossohm”: When watching this scene it made me feel like I was doing it all wrong. What exactly? Idk [I don’t know], life? Sitting here, on my ipad, cell in one hand and tv on... when I’m up to date on stupid status updates in actuality I’m missing out. I think I want to spend my time on this earth in a different light. Light as in, the sun lol. Out and be humbled to experience how others around the world enjoy living. Cuz I know I’m not. In a single paragraph cherryblossohm has confirmed the sad truth of Forster’s prophetic tale. I just hope for all our sakes that he got at least one thing wrong. After all, we will be in for one hell of a shock if the machine does ever stop working.  History today according to the BBC The front page of today’s BBC news website reveals a great deal about how historical events impinge on the present. This needs to be seen as indicative of a widespread obsession with the past. But it shouldn’t make us overlook the fact that the primary interest is current affairs. Simply put, history needs to have some contemporary resonance in order to count as “news”. This is the case with the deaths of two men in their 90s. Their passing is, of course, a personal loss to their friends and relatives. I never knew them, but I am invited to pay my respects because these two gentlemen feature in the collective consciousness. This is due to two events that form part of the national story, namely the Jarrow March of 1936 and the experiences of Britons incarcerated overseas during the Second World War. The demise of Con Shiels (the last survivor of the Jarrow March) and Alfie Fripp (a veteran of no fewer than twelve POW camps) marks the moment when two iconic occurrences pass from lived experience to “history”. This liminal moment gives the past a special frisson. We watch as the final living link to a momentous event is broken. This is history in the making. There are lots of other issues that flow from these particular stories. Is history made by the many or the heroic (or villainous) few? Can we learn from “everyday heroes” like Con Shiels and Alfie Fripp? If so, what part (if any) do we play in history? And what actually counts as a historical event? How influential was the Jarrow March? Did it change the course of history? Or is its significance given undue importance by subsequent commentators? In the BBC’s report of the death of Con Shiels it is notable that the trade unionist, Steve Turner is quoted calling for a “new ‘rage against poverty’”. Similarly, in 2011 the Jarrow March was re-enacted to mark its 75th anniversary and draw attention to youth unemployment. This demonstrates how a historical “fact” is nothing without interpretation. And this makes it inevitable that the politics of the present will get woven into the patterns of the past. The Jarrow example provides a flavour of things to come. Get ready for the bickering and arguing that will be triggered when Margaret Thatcher dies! The shadow of the Iron Lady looms large over another historically-flavoured news story: the status of the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas). This latest episode relates to Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s open letter to British prime minister, David Cameron in which she decries the continuance of “a blatant exercise of 19th-century colonialism” and calls for a negotiated solution as urged by the General Assembly of the United Nations way back in 1965. Interestingly enough, one of the BBC web links connected to de Kirchner’s rhetorical salvo refers to new documents released under the British government’s 30-year rule. These reveal just how surprised Thatcher was by the Argentine invasion. Access or restrictions concerning such primary evidence play a crucial role in determining how history gets written and re-written. Another link stemming from the latest crisis facing the Falkland Islands reminds us of the glorious / tragic events of 1982 via the commemorative events marking the thirtieth anniversary of the end of the Anglo-Argentine war. An anniversary such as this represents an additional way in which the past enters the present. The commemorative re-enactment of the Jarrow March is a case in point. A further example is to be seen amongst today’s crop of news stories, namely the centenary of Rhiwbina garden village in Cardiff. But what about events of today that are destined to become tomorrow’s history? Well, the year that has just passed has gone down in the record books as the “second wettest on record”. There is reason to believe that this will soon be surpassed, with reports that “extreme rainfall” is on the rise. And this is an appropriately apocalyptic note to end this account of history today. Because one of the factors motivating our love of the past is a widespread anxiety about the future. History’s near cousin is nostalgia. Poverty, unemployment and war take on a rosy hue thanks to the patina of time. Using the vantage point of the present we know that things worked out alright in the end... Or did they? New research seems to confirm what many have long suspected: King Ramesses III was murdered, probably by having his throat cut sometime around the year 1155BC. This is reported by the BBC alongside a small photograph of the king’s mummified visage.(1) He looks strangely familiar... and then it struck me how much he reminds me of the late, great expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka. I wonder if their DNA crossed at some point over the past few millennia?

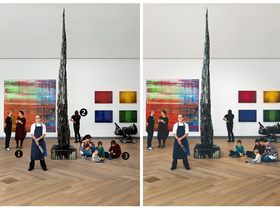

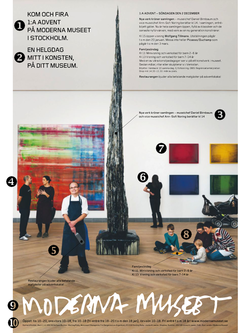

___ Note (1) Michelle Roberts, “King Ramesses III’s throat was slit, analysis reveals”, BBC News, 18/12/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-20755264  “Swedish weapons with Burma’s army”. So reads a two-page article in today’s issue of the newspaper, Svenska Dagbladet.(1) Alongside the text are photographs indicating that the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) has come under attack from Burmese soldiers armed with Saab AB’s Carl Gustav 84mm Recoilless Rifle (“The best multi-purpose weapon there is”). We know this because at least one such armament plus ammunition were left behind when the state’s forces were driven into a retreat by their KIA opponents. A serial number – 17248 – is clearly visible on the weapon pictured in Svenska Dagbladet. This should make it simple for Saab AB to confirm whether it was exported directly to Burma (in contravention of the 1996 EU export embargo) or, as is far more likely, that the arms found their way to Myanmar via one of Saab AB’s official customers (probably India or Thailand). This mishap should come as no surprise given the sheer quantity of Swedish-made arms that are being exported all over the world. However, what makes this particular incident noteworthy is the manner in which Svenska Dagbladet reported the news. At the very same time that it broke the story, the newspaper’s editors allowed a 32-page advertising feature to be inserted into that day’s paper. Entitled, Rikets säkerhet (The Nation’s Security), it is produced by MDG Magazines and edited by Christer Fälldin. In his introductory message Fälldin informs Svenska Dagbladet’s readers that this addition to their daily paper tackles what he considers to be one of the most significant political challenges facing Sweden, namely defence. Fälldin has therefore sought to use the inaugural issue of Rikets säkerhet to address “many of the security and defence issues” that are current today. Alas, one such issue that is missing from this “newspaper” (sic) is any discussion of the legal or moral dimensions of the arms industry and the responsibilities that Sweden has as a world-leading exporter of military equipment. The fact that the first issue of Rikets säkerhet was allowed to subsume Svenska Dagbladet’s report into the inherent risks involved in exporting arms is highly revealing. It exposes the extensive lobbying campaigns undertaken by powerful groups and individuals with vested interests in normalising and enhancing Sweden’s weapons industry. Rikets säkerhet represents a sophisticated attempt to scare the Swedish people by confronting them with amorphous threats and worries about the future. These dire warnings appear alongside advertisements from all manner of military-related organisations. They are in turn interspersed with associated “news” stories. This pseudo journalism is a thinly veiled attempt to convince Sweden’s political elite to continue to invest ever increasing sums in defence procurement and development. All this is a far cry from the Nobel-prize and IKEA-meatball image of Sweden so adored by the international media. Beneath an oh-so-sweet Nordic façade there festers a far from savoury side to Sweden. Just ask the people of northern Burma. ___ Note (1) Bertil Lintner, “Svenska vapen hos Burmas armé”, Svenska Dagbladet, 11 December 2012, pp. 20-21.  Moderna Museet online (left) and in print (right) Earlier this month I reflected on a fascinating newspaper advertisement for Sweden’s Moderna Museet. Additional investigation has now turned this commentary into a spot-the-difference. On the museum’s website is a promotional feature that includes the same image.(i) Only, on closer inspection, it becomes apparent that it differs from the version that appeared in the newspaper, Dagens Nyheter. 1 The invigilator’s clothing has been darkened. This ensures that she wears the attire of the art lover (i.e. dressed entirely in black). The same is true of the trousers worn by the visitor (2). 2 The visitor has been shifted further to the right. In the online image it looks as if she is reading a label next to the work rather than looking at the art itself. This risked introducing a troublesome piece of interpretation – a barrier preventing her from being in the midst of the art (mitt i konsten). This is alleviated by shifting the visitor closer to the art (although not too close given that the all-important pushchair is still in the way). 3 The posture of the hands-on art educator has changed. Her rather motherly pose is replaced by a less overtly protective position in relation to the three children. This prevents her from coming between them and the art (again ensuring that they are mitt i konsten). In the image on the left the children and the facilitator have their back to Sterling Ruby’s Monument Stalagmite. The print version spins them around such that all the group members are oriented towards the sculpture. All this confirms the meticulous attention that has gone into this carefully crafted framing of Moderna Museet. A genuinely artful and art full advertisement. ___ Note (i) “Fira 1:a advent på Moderna Museet”, http://www.modernamuseet.se/sv/Stockholm/Nyheter/2012/Fira-1a-advent-pa-Moderna-Museet/. The image is credited to the photographer, Åsa Lundén.  Today’s issue of the newspaper, Dagens Nyheter features a full-page advertisement for Moderna Museet – Sweden’s national museum of modern and contemporary art. Every art lover knows that a picture is worth a thousand words. So, with this in mind, I’ve picked out ten points of interest and used them to structure a one thousand word reflection on this most artful of advertisements: 1 Moderna Museet is a place of celebration for all. This is important to stress at the outset because some misguided people continue to insist on treating our museums as either mausoleums or bastions of elitist culture. Moderna Museet isn’t like that. It’s a place to come and have fun; to celebrate things like the start of the Christmas period. And what better way to escape the commercialisation of this sacred event than by going on a pilgrimage to a secular temple of art such as Moderna Museet. 2 Moderna Museet puts you in the picture: when there you will be in the midst of art – your art, your museum (mitt i konsten, på ditt museum). 3 The director and his deputy have given up their holiday to greet the visitors. Tomorrow afternoon – Sunday 2 December – Daniel Birnbaum and Ann-Sofi Noring will talk about their latest acquisitions. In so doing they affirm that Moderna Museet is living up to its reputation: it is filled both with modern Old Masters (fylld av klassiker) and “with the work of a new generation of artists” (med verk av en ny generation konstnärer). These new works, we are told, “crown the collection” (kröner samlingen). They also enable the recently appointed director to put his mark on the museum. This raises lots of fascinating questions: What has the museum acquired under this leader that it might not have under its predecessor? Which criteria are used when choosing what to buy? Who makes the decisions? What did the purchases cost? Who are the donors? Who are the artists? And what personal connections link them with Birnbaum and his colleagues? Will any of these questions be addressed when the director speaks? They certainly should be, after all, this is your museum. 4 Who are these people so deep in conversation? A perfect pair: enthusiastic gesture is met with rapt attention. These two are clearly art lovers. But they aren’t visitors. Nor are they security guards. Instead they are young, trendy invigilators just waiting to share their love of art with the museum’s well-behaved guests. How do we know that they are art lovers? Their gestures and their clothes say it all (see 6). 5 This isn’t an art lover, but he looks nice and friendly. He’s carrying the tool of his trade and wearing his work clothes (just like the couple in 4). But his place of work isn’t the galleries. Nevertheless, rather than being marginalised, this menial worker is given pride of place. Indeed, he looks rather like a work of art: culinary art. Because Moderna Museet isn’t just about consuming art. It’s a place to eat and socialise. That’s why the chef is important enough to be included here. But he isn’t that special. His name is not given. Nor are those of the two invigilators. In fact, only two people are referred to by their names. And neither of them is visible. Standing in as substitutes for the director and his deputy are the artworks that they have sanctified by choosing to include them in the collections of Moderna Museet. The art stands for them. It embodies them. Thus Sterling Ruby’s Monument Stalagmite could be renamed: Monument Birnbaum. It’s a bold assertion of his fitness to lead; his regal good taste (thanks to this and the other acquisitions that “crown the collection”). 6 This person adopts the ideal art pose, with one hand on hip, the other touching the face in a gesture of deep contemplation. She wears the uniform of the art lover, dressed as she is entirely in black. She is part of the same tribe as the invigilators (4) who serve as acolytes assisting at the altar of High Art. This true believer is standing at a respectful distance from the art, not touching but visually consuming. Unfortunately, she is not able to stand directly in front of this particular artwork because there is an object is in the way. But this is not a sculpture; it’s a child’s pushchair! This obstacle is not just there by chance. It’s as symbolic as any of the paintings on the wall. It says: this is an accessible, family-friendly museum in which children are welcome (see 8). 7 The art is shown in glorious isolation in this pristine, white-cubed gallery. This lends it a spurious, “neutral” quality in which nothing comes between us and the art (we are, after all, “mitt i konsten” (1)). There is not a label or interpretation panel in sight. None of the works are literally framed in the sense of there being borders around the paintings or separate plinths under the sculptures. But they are framed in all sorts of other ways. This advertisement and all its messages (overt and subliminal) are frames. Art never speaks for itself, no matter how white and bare the walls. 8 We have already been reassured that the museum is not a mausoleum (1). Now we are reminded that it is not a library either. It’s a playground – for art lovers, young and old. Perhaps this trio of immaculately behaved children will one day be the artists (or museum directors) of the future? With luck they will grow up to wear black clothes and feel as at home in the museum as the lady in 6. The art instructor – just like the proud parent – does her best to make this a reality: she acts as a mediator of the art. She and the other parents and guardians are surrogates of the invigilators seen in 4. During the years 2004-2011 “Zon Moderna” served as the forum for Moderna Museet’s youngest guests. This initiative has been disbanded by the current director. But he is not reducing the museum’s commitment to children. Far from it: they are now brought into the bosom of the museum (mitt i konsten). Zon Moderna ran the risk of being dismissed as a case of “ghettoisation”: “an area specifically reserved for extra activities, and largely containing children within these spaces” (Gillian Thomas, “‘Why are you playing at washing up again?’ Some reasons and methods for developing exhibitions for children” in Roger Miles & Lauro Zavala (eds) Towards the Museum of the Future: New European Perspectives, London and New York: Routledge, 1994, p. 118.) The kids visible in this advertisement are not relegated to some sort of out-of-sight ghetto: we see them as they are just about to scribble away on the floor of the museum, centimetres from the museum’s latest priceless acquisition (5). 9 The museum’s logo adds to the friendly atmosphere: a personal signature which is actually a work of art, based as it is on Robert Rauschenberg’s handwriting. How long will it be before the museum decides to rebrand and ditch this naff typeface? 10 The museum is open every day except Mondays. There is even free entry on extended Friday evenings – perfect for those trendy young things that opt to stay on to drink in the museum’s newest space: a bar. There was a time when Moderna Museet – like all Sweden’s national museums – was free for all: now adults must pay because the current government says so. But the most important visitors still get in for free, namely children up to 18 years old. With luck, by the time they reach maturity they will have blossomed into the sorts of adults seen in this advertisement. They will thus be willing to pay to enter the museum and reacquaint themselves the fresh acquisitions that are to be introduced tomorrow: these are the works that today’s children will grow up with and later recognise as canonical works in their own personal museums of art. This recognition and sense of ownership will help ease the awkward truth that, by charging its citizens to enter Sweden’s Moderna Museet, they will actually be paying twice. After all, their high taxes have already paid for the museum. Their museum.  On Sunday 11 November a fascinating debate took place at Arkitekturmuseet (Sweden’s national museum of architecture). It marked the culmination of a weekend of activities to celebrate the institution’s fiftieth anniversary. Events included guided tours of the Rafael Moneo-designed building which Arkitekturmuseet shares with another of Sweden’s state museums, namely Moderna Museet. The highlight of the festivities focused on the commemorative publication, The Swedish Museum of Architecture: A Fifty Year Perspective. This was launched following a series of reflections by two contributors to the book, Thordis Arrhenius and Bengt O.H. Johansson (the latter was director of the museum from 1966-77). This was followed by a panel debate entitled “Midlife crisis or stroppy teenager? A discussion about Arkitekturmuseet yesterday, today, tomorrow”.(1) It was at this point that matters started to get interesting. It quickly became apparent that the past, present and future of Arkitekturmuseet are far from settled. Much attention was given to the recently expanded role of the museum. This is summed up in an introductory section of the anniversary book. Under the rubric, “More than a museum”, Monica Fundin Pourshahidi cites a press release by the Swedish minister of culture, Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth in which it is stated that, from 2009 onwards, Arkitekturmuseet is vested with being a “power centre” not only for architecture but also for design: “The Museum of Architecture can and must be a display window and a distinct voice in the debate on social planning, architecture, design and sustainable development”.(2) This point was taken up by Arkitekturmuseet’s present director, Lena Rahoult. But her positive spin was immediately problematised by a fellow panel member, the architectural historian Martin Rörby. The focus of his criticisms was a recent governmental memorandum which instructed the institution to engage in “promotion and communication” (främjande och kommunikation) rather than “traditional museum activities” (traditionell museiverksamhet). This would be best signalled by a change in title, with the word “museum” being replaced by “centre” or “arena”.(3) Rörby expressed reservations about such a shift in focus, fearing that an increase in breadth would come at the expense of depth and critical engagement. He was also troubled by the vague, empty rhetoric of the memorandum. On the other hand, the notion of going beyond what was expected of a “traditional” museum was nothing new. Rörby illustrated this point by citing Arkitekturmuseet’s past involvement in the often heated debate regarding Sergels torg in central Stockholm. He stressed the rapidity of the museum’s response which enabled it to react to a pressing, contemporary issue. This active engagement, however, was only possible because of the museum’s unrivalled collections of artefacts, architectural models and other archival documents. Rörby was of the opinion that the museum would find it far harder – if not impossible – to arrange such an exhibition in the additional field of design. This is because the museum responsible for the national design collection is another entirely separate institution, namely Nationalmuseum. The design holdings will remain there, despite Arkitekturmuseet’s increased mandate. In the light of this one can be forgiven for questioning the basis for adding design to the museum of architecture. The oddness of this situation was beautifully demonstrated by the fact that, at the very same time that this debate was unfolding at Arkitekturmuseet, Nationalmuseum just down the road was holding a “theme day” on “handicraft, time and creativity” in association with its craft and design exhibition, Slow Art.(4) Way back in the late 1980s and early 1990s the museum fraternity in Sweden dreamed of a museum of industrial design (Konstindustrimuseet) being housed in Tullhuset adjacent to the main Nationalmuseum building in the Blasieholmen area of Stockholm. This nineteenth century toll house was to have been expanded to allow for 5000 square metres of exhibition space. Alas, this imaginative idea proved abortive, as did a plan to deploy the spectacular Amiralitetshuset on the island of Skeppsholmen.(5) In the wake of these failed initiatives comes the current half-baked decision to place the design burden on the ill-equipped museum of architecture. Meanwhile, in February 2013, Nationalmuseum will close for a period of four years during which time a multi-million kronor refurbishment will take place. This, one would have thought, would be the ideal opportunity to resolve the status of design in Sweden. The risk is that the investment in Nationalmuseum is being made against a contested, confused and contradictory context. Exacerbating this frankly farcical state of affairs is the added complication of Arkitekturmuseet’s relationship with Moderna Museet. These two museums, as has been noted, share a building. One might therefore have thought that it would sensible for the pair to unite, especially given the enlarged remit of Arkitekturmuseet. Indeed, in 1998 it was proposed that modern design dating from 1900 onwards should be moved to Moderna Museet.(6) On being asked about the relationship with her neighbour, Arkitekturmuseet’s director Lena Rahoult made a few platitudinous comments and paid compliments to Daniel Birnbaum, her counterpart at Moderna Museet. However, when it comes to Moderna Museet’s upcoming exhibition on Le Corbusier, it emerged that the museum of architecture will not be involved.(7) This, it strikes me, represents a potentially serious threat to the autonomy of Arkitekturmuseet. If the Le Corbusier exhibition is a success despite (or perhaps because of) the exclusion of Arkitekturmuseet, then the argument is being made that Moderna Museet is more than capable of taking over this field. Daniel Birnbaum would no doubt be delighted. He is a very shrewd operator. Upon taking over the running of Moderna Museet he erased all trace of its former director in the most charming manner: by turning the whole museum over to photography. This had a number of consequences. It facilitated a tabula rasa whilst showing Birnbaum to be both innovative and in step with the history of the museum. This in turn stifled any potential suggestion that photography was not being accorded sufficient attention. This was a smart move given that the formerly separate museum of photography had been subsumed into the collections of Moderna Museet on the completion of Rafael Moneo’s building in 1998. With this potential criticism snuffed out, Birnbaum then set about curtailing the independence of the museum’s satellite institution, Moderna Museet Malmö. This was led by Magnus Jensner until a “restructuring” made his position untenable and prompted his resignation.(8) In March of this year Jensner was succeeded by Birnbaum’s man in Stockholm, John Peter Nilsson. Against the background of these strategic manoeuvres the decision to mount an exhibition on Le Corbusier at Moderna Museet is no mere innocent happenstance. It can be interpreted as part of a calculated empire building process. And, if the recent debate at Arkitekturmuseet is anything to go by, Birnbaum is a giant among pygmies on the Swedish cultural scene. Perhaps mindful of this, at the same time as spouting her platitudes, Lena Rahoult has been busy mounting the barricades. She has taken the decision to withdraw Arkitekturmuseet from the bookstore that it has shared with Moderna Museet since the inception of Moneo’s building. All the books are being sold at a reduction of 60% whilst magazines and postcards are being flogged off for a few kronor. Once this stock has been disposed, Arkitekturmuseet will open a separate retail establishment in its own part of the locale. This development is notable given that the bookstore was one of the very few aspects of the building where the two institutions merged. Another is the shared ticket desk. Moneo designed the building to incorporate the old drill-hall where Moderna Museet began life and which is now occupied by Arkitekturmuseet. In so doing he provided a new entrance and closed the original doorway. Rahoult plans to reopen this entrance whilst keeping the other in use. Birnbaum is on record as describing this proposal as “ludicrous” (befängd).(9) Well he might, because one of the main criticisms of Moneo’s building is its very modest and hard-to-find entrance. Should Arkitekturmuseet prove to be the main gateway into the combined museum it may well increase the number of visitors to the architecture collection, but it will draw attention from what is currently the dominant partner, Moderna Museet. The proposed changes to the shop and entrance have led to claims that Arkitekturmuseet wishes to “break free from Moderna Museet”.(10) The paradoxical situation has therefore arisen whereby, at the same time that Arkitekturmuseet struggles to work across disciplines in one direction, it is placing barriers to the museum next door. There is, of course, no reason why different disciplines should not be brought together in a single museum. A case in point is the Museum of Modern Art, MOMA. Its mission statement is grounded in the belief [t]hat modern and contemporary art transcend national boundaries and involve all forms of visual expression, including painting and sculpture, drawings, prints and illustrated books, photography, architecture and design, and film and video, as well as new forms yet to be developed or understood, that reflect and explore the artistic issues of the era.(11) Another example closer to home is Norway. However, in this case the forced union of art, architecture and design has been far from amicable or straightforward. But at least Norway’s National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design is being given a grand new building in which to unite. This is not the case in Sweden. No one should be surprised about this given the paltry cultural policies of the present alliance government under the stewardship of its mediocre minister of culture, Lena Adelsohn Liljeroth. When it came to the festivities to mark Arkitekturmuseet’s jubilee debate, the icing on the birthday cake occurred when the panel turned to the audience for questions and response. Up stepped Jöran Lindvall. He remains – as he was at pains to make clear – the longest serving director of Arkitekturmuseet (during the years 1985-1999). Nevertheless, he added pointedly, no one had thought to ask him to contribute to the fiftieth anniversary publication. His absence from its pages was a timely reminder that such official records are as partial as they are political. That much is shown by a similar publication released to mark Moderna Museet’s own fiftieth anniversary in 2008. Such historical tomes might seem to be rooted in the past, but their main aim is to seek to placate the politicised present whilst simultaneously shaping the uncertain future. As if to underline this, Jöran Lindvall presented the current holder of the post he once occupied with a bag stuffed full of newspaper cuttings and other documents from his private collection relating to exhibitions that took place during his time at the museum. He declared his willingness to donate these to Arkitekturmuseet, but on one condition: that it remain a museum devoted to architecture. Lena Rahoult accepted this generous offer. She could hardly do otherwise. It will be interesting to follow the fate of Lindvall’s loaded gift. Indeed, all those involved in museums would do well to keep track of events in Sweden and watch with interest as commentators, practitioners, museum professionals and politicians plot their next moves in a battle that is more comedy than tragedy. But that is not to say that the outcome is likely to leave very many people laughing. _____ Notes (1) The panel participants were the director of Arkitekturmuseet, Lena Rahoult together with Fredrik Kjellgren (architect), Petrus Palmér (designer), Birgitta Ramdell (director of Form/Design centre, Malmö) and the architectural historian Martin Rörby (Skönhetsrådet). The chair was Kristina Hultman. (2) Press release dated 19 December 2008, cited in Main Zimm (ed.) The Swedish Museum of Architecture: A Fifty Year Perspective, Stockholm: Arkitekturmuseet, p. 4. (3) Cited in “Stora förändringar föreslås på Arkitekturmuseet”, Arkitektur, undated, http://www.arkitektur.se/stora-forandringar-foreslas-pa-arkitekturmuseet (accessed 12/11/2012). (4) Slow Art, Nationalmuseum, 10 May 2012 – 3 February 2013. The special event that took place on Sunday 11 November included a talk by Cilla Robach (“Slow Art – om hantverk, tid och kreativitet”) followed by a craft activity for children (see the advertisement on p. 7 of the Kultur section of that day’s issue of the newspaper, Dagens Nyheter). (5) Mikael Ahlund (ed.) Konst kräver rum. Nationalmuseums historia och framtid, Nationalmusei skriftserie 17, 2002, pp. 76-77. (6) Ahlund, 2002, p. 77. (7) Moderna Museet’s exhibition has been given the name “Moment – Le Corbusier’s Secret Laboratory” and will run from 19 January – 28 April 2013. The decision not to collaborate with Arkitekturmuseet is ironic given that the latter put together the exhibition “Le Corbusier and Stockholm” in 1987. (8) “Magnus Jensner slutar i Malmö”, Expressen, 20/10/2012, http://www.expressen.se/kvp/magnus-jensner-slutar-i-malmo. (9) “Arkitekturmuseets femtioårskris – en intervju”, Arkitektur, undated, http://www.arkitektur.se/arkitekturmuseets-femtioarskris-en-intervju (accessed 12/11/2012). (10) Hanna Weiderud, “Arkitekturmuseet bryter sig loss från Moderna”, SVT, 01/11/2012, http://www.svt.se/nyheter/regionalt/abc/arkitekturmuseet-bryter-sig-loss-fran-moderna. (11) Collections Management Policy, The Museum of Modern Art, available at, http://www.moma.org/docs/explore/CollectionsMgmtPolicyMoMA_Oct10.pdf. A lovely example of “banal Nordism” cropped up in the

BBC Radio 4 comedy programme, Clayton Grange. In this week’s episode our spectacularly stupid scientists “attempt to make war just a bit more gentle” – a bit more Swedish. Few listeners would suspect that this purportedly most peaceful place on the planet is in reality the home of Saab AB, the proud producer of the Carl-Gustaf system – “the best multi-purpose weapon there is”.  The British Museum possesses many thousands of fascinating objects. One of its self-styled “highlights” is a rather plain looking marble inscription. It comes from Rome and is dated around AD 193-211. What makes it so interesting are the things it does not show. These include the names of two relatives of the Roman emperor, Septimius Severus (AD 145-211), namely his daughter-in-law Plautilla and his son Geta. The latter was murdered by Septimius Severus’ other son Caracalla. He was Plautilla’s husband and Geta’s brother. The two siblings were bitter rivals following the death of their father. It is believed that Caracalla murdered Geta and then had his treacherous and much despised wife executed. And, to make matters even worse, they were then subjected to the posthumous punishment of damnatio memoriae: their names were expunged from all official records and inscriptions and their statues and all images of them were destroyed. This process [damnatio memoriae] was the most horrendous fate a Roman could suffer, as it removed him from the memory of society.(1) However, removing Geta from public consciousness was not a straightforward matter. Caracalla was obliged to give his brother a proper funeral and burial due to Geta’s popularity both with the Roman army and among substantial sections of Roman society. This explains why the names of Geta and Plautilla were included on the British Museum’s marble inscription, only to be scratched out later on. Why am I mentioning all this? Because a modern-day form of damnatio memoriae is currently unfolding in British society. This is in relation to the disc jockey, children’s television presenter and media celebrity, Sir Jimmy Savile OBE, KCSG, LLD (1926-2011). When he died last year at the ripe old age of 84 he was hailed a loveable hero who had done much for charity. Now, however, revelations have come to light suggesting that he was, in the words of the police, a “predatory sex offender”.(2) As a result, strenuous efforts are being made to expunge him from the public record.(3) Thus, the charity that bears his name is considering a rebrand. A plaque attached to his former home in Scarborough was vandalised and has since been removed. So too has the sign denoting “Savile’s View” in the same town. Meanwhile, in Leeds, his name has been deleted from a list of great achievers at the Civic Hall. A statue in Glasgow has been taken down in an act of officially sanctioned iconoclasm. The same fate has been dished out to the elaborate headstone marking Savile’s grave. This last-named act of damnatio memoriae is in some ways a pity given the unintended poignancy of the epitaph inscribed on the stone: “It Was Good While It Lasted”. It was almost as if Savile knew that he would one day have to atone for his evil deeds. Atonement has, alas, come too late for those that suffered at the hands of Savile. To make matters worse, his considerable fame has been replaced by a burgeoning notoriety. This is reminiscent of the damnatio memoriae that befell Geta and his sister-in-law Plautilla. The marble inscription that once carried their name is a “highlight” of the British Museum precisely because of the dark deeds associated with them and the futile efforts made to delete them from history. In their case, damnatio memoriae has, in a perverse way, enhanced their posthumous status centuries after their grisly deaths. Let’s hope that the same will not be said of the late Jimmy Savile – an individual who has gone from saint to scoundrel in the space of just a few short months. ___ Notes (1) “Marble inscription with damnatio memoriae of Geta, son of Septimius Severus” (Roman, AD 193-211, from Rome, Italy, height 81.5 cm, width 47.5 cm, British Museum, Townley Collection, GR 1805.7-3.210, http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/gr/m/marble_inscription.aspx). (2) Martin Beckford, “Sir Jimmy Savile was a ‘predatory sex offender’, police say”, The Daily Telegraph, 09/10/2012, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/crime/9597158/Sir-Jimmy-Savile-was-a-predatory-sex-offender-police-say.html. (3) “Jimmy Savile’s headstone removed from Scarborough cemetery” and “Sir Jimmy Savile Scarborough footpath sign removed”, BBC News, 12/10 & 08/10/2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-19893373 and www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-york-north-yorkshire-19867893.  A forgotten painting by the little-known American artist, Mark Rothko has been rediscovered at a London museum. Experts had previously considered Tate Modern’s “Yellow on Moron” to have been executed by the Polish master, Wlodzimierz Umaniec (spelt Vladimir Umanets). However, a novel technique known as a vandal-spectrometry has enabled scientists to detect traces of crudely applied oil paint beneath Umanets’ trademark scrawl. This has prompted art historians to rename the work “Black on Maroon” and determine that it is part of Rothko’s abortive Seagram murals. Inevitably, this reattribution has reduced the value of the piece. It has, however, increased interest in genuine works by Vladimir Umanets. This towering modern-day genius has been likened to the bastard spawn of Marcel Duchamp and Cy Twombly.  Hillsborough: The Report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel has just been published. This 400-page document investigates an incident which occurred on 15th April 1989 at the Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield. On that awful day a soccer match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest had to be abandoned when the Leppings Lane stand became overcrowded. The ensuing crush led to the death of 96 Liverpool football fans. This terrible loss of life and the unbearable grief of their loved ones have been compounded over the past 23 years by a deliberate and systematic attempt to cover up what happened. That much is clear from the report released today. One of its most startling findings relates to the fact that written statements made at the time by police officers and members of the South Yorkshire Metropolitan Ambulance Service were altered. Why? The answer is emphatic: “Some 116 of the 164 [police] statements identified for substantive amendment were amended to remove or alter comments unfavourable to SYP [South Yorkshire Police].”(1) In other words, our supposed custodians of law and order – both then and since – have been more interested in their own image and reputation than in finding out what went so catastrophically wrong. And this, I argue, is why a so-called “academic” subject such as History is so vital to a democratic and viable society. Compare the contemporary example set out above with this quotation from The Historian’s Craft by Marc Bloch: One of the most difficult tasks of the historian is that of assembling those documents which he [or she] considers necessary... Despite what the beginners sometimes seem to imagine, documents do not suddenly materialize, in one place or another, as if by some mysterious decree of the gods. Their presence or absence in the depths of this archive or that library are due to human causes which by no means elude analysis. The problems posed by their transmission, far from having importance only for the technical experts, are most intimately connected with the life of the past, for what is at stake is nothing less than the passing down of memory from one generation to another. Bloch had no need to restrict his attention to “the life of the past”. Because “the passing down of memory from one generation to another” occurs in the here and now. The Hillsborough disaster is history. But its living legacies are life, truth and justice in the present. These qualities should be our memorial to ten-year-old Jon-Paul Gilhooley who, together with 95 fellow supporters, became the innocent victim of official incompetence, misconduct and suppression on that fateful day in April 1989. ____ Notes (1) Hillsborough: The Report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel, September 2012, HC 581, London: The Stationery Office, p. 339. (2) Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004, pp. 57-59.  “Nothing like commemorating an event to help you forget it.” So wrote Art Spiegelman in his cathartic book, In the Shadow of No Towers (2004). This monumental tome is an analogue to the Twin Towers that Spiegelman saw vanish from the place this self-styled “‘rooted’ cosmopolitan” calls home. I am reading Spiegelman’s book to help me write my own work of memorialisation under the provisional title, “Forked no lightning: remembering and forgetting in the shadow of Big Ben”. Half-way through In the Shadow of No Towers, Spiegelman recalls feeling asphyxiated by the flag-waving nationalism that characterised the “mind-numbing 2002 ‘anniversary’ event” (p.5). A year later the same date left him railing against the exact same “jingoistic strutting” (p. 10). So perhaps Spiegelman was right to argue that there really is nothing like a good (or bad) commemoration to help you forget something? Then it struck me: today is Tuesday 11th September! It’s gone 9 pm as I write, which means that almost an entire “9/11” has passed by without comment from family, friends, colleagues, strangers or those hourly BBC Radio 4 news bulletins that punctuate my day. “The unmentionable odour of death offends the September night”. So wrote W.H. Auden in his poem “September 1st, 1939”. In 2003, Spiegelman asserted that this odour “still offends as we commemorate two years of squandered chances to bring the community of nations together” (p.10). Many more chances have been missed since then. But at least the air seems to have cleared. Indeed, the breeze is so brisk that it appears to have blown away the cobwebs of 9/11 entirely. I guess we’ll just have to wait for a nice round number before we start remembering again... And with that thought I slide my battered copy of In the Shadow of No Towers back into the oblivion of my bookcase. A lot of dust is destined to gather before a frisson of nostalgia prompts me to reach for it once again on 9/11/2021. _________ Supplemental 1 I stand corrected. BBC Radio 4’s “The World Tonight” at 10 o’clock has just referred to the anniversary of 9/11. It did so in relation to the Stars and Stripes that was hanging at half-mast at the US Embassy in Cairo. Why was this mournful flag mentioned? Because protestors stormed the compound, tore it down and replaced it with an Islamist banner. They were angered by the imminent release of the film Innocence of Muslims. This appears to have some connection to Florida Pastor and part-time religious book burner, Terry Jones.(1) I do hope that news of this depressing incident doesn’t reach Art Spiegelman. It’ll simply confirm his despairing belief that “brigands suffering from war fever have since hijacked those tragic events…” (p. 4). ___ Note (1) For the background to this story and its deadly consequences see Matt Bradley and Dion Nissenbaum, “U.S. Missions Stormed in Libya, Egypt”, The Wall Street Journal, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10000872396390444017504577645681057498266.html _________ Supplemental 2 12/09/2012 This affair becomes more tragic with every passing hour. Reports from Libya indicate that at least four consulate staff - including US ambassador, J. Christopher Stevens - have been killed. What a tragic act of pseudo commemoration._  Jamtli is a regional museum in the city of Östersund in central Sweden. In recent days it has been blessed with a great deal of attention. At first this delighted its director, Henrik Zipsane. “All publicity is good publicity” he declared in a newspaper interview last week.(1) Zipsane must have been cursing those words as he announced the cancellation of Jamtli’s exhibition “Udda och jämt” (Odd and even). This was to have been a group show of contemporary Swedish art. Included in the line-up was Lars Vilks. He made a name for himself in 2007 with the publication of his drawings of the prophet Muhammad as a dog-shaped piece of street furniture. This triggered a furious and at times very violent reaction in both Sweden and abroad. Vilks is now obliged to live under police protection and has become synonymous with the polarised views pertaining to religion and freedom of expression. Whatever one’s opinion of Vilks, it is impossible to accuse him of hiding his views on such matters. This is confirmed by his much-publicised decision to travel to New York this month in order to take part in a conference entitled SION (Stop Islamization of Nations). Nevertheless, it seems to have been this specific action that led Jamtli’s leadership to change their mind about including Vilks in “Udda och jämt”. Yet they clearly failed to think through the potential consequences of this move. One by one the other artists in the show announced their decision to withdraw. Eventually it became clear that not enough participants remained and so the exhibition, which was due to open on 30th September, has now been cancelled. This incident touches on lots of highly sensitive issues and gives rise to a host of often strongly held opinions. Oddly enough it is this that appears to be the greatest problem. Earlier this morning a spokesperson for Jamtli appeared on Sweden’s national radio. She lamented that the debate that had arisen threatened to overshadow the art. If this is such a bad thing, why extend an initiation to a so-called conceptual artist like Lars Vilks in the first place? Could it be that Jamtli hoped that Vilks’ presence might have added a touch of spice to the mix – a little of that “good publicity” so craved by Zipsane? If so, this has all gone horribly wrong. Or has it? “Udda och jämt” promises to be one of the most talked about shows in Jamtli’s history – whether it takes place or not. So why don’t its asinine leaders go ahead with the exhibition as arranged? The plans are no doubt well advanced; the text panels and labels for each artwork must be ready to be go. These could be mounted on the wall alongside works by those artists who still wish to participate. Meanwhile, large tracts of white space would indicate those works that have been censored by the institution or self-censored by the artists. Each (non)participant plus other interested commentators could be invited along to the opening. They could enter into debate over what has occurred, why and with what consequences. Each of the artists selected to take part in “Udda och jämt” would be compelled to explain their decisions. Did they withdraw in protest against the museum’s censorship, in support of Lars Vilks or for some other reason? One such protagonist is the painter, Karin Mamma Andersson. She is on record as criticising Jamtli’s belated and apparently arbitrary decision to ban Vilks. But, prior to that, she was presumably happy for one of her paintings to share a wall with a work by Vilks? Or was she unaware of his participation? Whichever was the case, what “Udda och jämt” reveals is the multivocality of artworks and the powerplays inherent in the artworld. Art and artists are constantly being reframed – by the media and by curators in museums. Art never “speaks for itself”. This has been confirmed by the Jamtli debacle. Yet, rather than capitalise on this rare opportunity to unpick the workings of the artworld, what does the museum do? Simply shuts its doors, withdraws from the fray and waits for normal service to resume. The greatest losers here are Jamtli’s public. Because if Jamtli’s leadership had the courage of their convictions and gone ahead with this non-show then something fascinating would have occurred: the audience itself would have taken centre stage. Regular museum-goers and first-time visitors alike could have voiced their opinions about this so-called public institution. Do they applaud or abhor the actions of the museum and the behaviour of the artists? The resulting dialogue would provide a roadmap for future decisions and contribute to an opening-up – a democratisation – of the museum. As it is, by cancelling “Udda och jämt” the likes of Henrik Zipsane have simply placed an embargo on proper debate. And it is this lack of informed discussion and argument that characterises the hysteria around religion and freedom of expression. The only winners here are those people who delight in spreading discord and miscommunication plus those misguided individuals and organisations who insist on separating “art” from life. ___ Note (1) “Jamtli ställer in utställning”, Svenska Dagbladet, 29/08/2012, http://www.svd.se/kultur/jamtli-staller-in-utstallning_7458194.svd.  There has been a spate of scare stories recently about the "threat" to "our" heritage. These often centre on fabulously valuable artworks owned by extremely wealthy people. Occasionally the objects in question have been hanging quietly on the wall of a public art gallery - until, that is, the owner dies or runs out of cash. A case in point is Picasso's Child with a Dove (1901). This is currently in limbo. It has been sold secretively to an unknown foreign buyer for an undisclosed sum (thought to be in the region of £50m).(1) Unfortunately, the new owner will have to wait a while before getting their hands on it. This is because Britain's minister of culture has placed a temporary ban on its export in the hope that sufficient money can be raised to "save" this item "for the nation". This is exactly what occurred just the other day in relation to a painting by Manet.(2) It cost the Ashmolean Museum £7.83m to "save" this integral piece of British culture from the rapacious hands of a dastardly foreigner. But don't believe this rhetoric. Oh, and ignore the headline price and touching tales of little street urchins parting with their pennies to rescue this relic. It took upwards of £20m in tax breaks and donations from public bodies to ensure that national pride remained intact. Yet this doesn't bode well for Picasso's little bird-loving child, does it? The art fund (sic) must surely have run out by now. So too have the superlatives and dramatic warnings from our media luvvies and museum moguls. Indeed, their fighting funds were already seriously depleted after they chose to place £95m in the hands of the Duke of Sutherland - one of the richest men in the country.(3) This act of Robin Hood in reverse stopped the robber baron from flogging two paintings by Titian along with other trinkets he and his family had so generously loaned to the National Galleries of Scotland. And now the same museum is coming under "threat" again! Soon we will have to watch as Picasso's little bird migrates to sunnier climes. The national heritage will be fatally winged by this terrible loss. The consequences just don't bear thinking about... This is just as well because, in truth, the only repercussions will be a slight dent to national pride plus a small gap on a museum wall. This can be filled by any number of artworks that are currently in store at the National Galleries of Scotland. Deathly quiet will then return to this mausoleum of art... Until, that is, we are panicked by the next siren call as yet another integral piece of Britain's (ha!) much-loved heritage comes under covetous foreign eyes. Tell the world. Tell this to everyone, wherever they are. Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies. 'Cos you never know, you might just see a sweet bird by Picasso fly by... ____ Notes (1) Anon, "Picasso's Child With A Dove in temporary export bar", BBC News, 17/08/12, http://www.bbc.co.uk./news/entertainment-arts-19283696; Maev Kennedy, "Picasso painting Child with a Dove barred from export", The Guardian, 17/08/12, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2012/aug/17/picasso-child-with-a-dove-painting. (2) Stuart Burch, "Manet money", 08/08/2012, http://www.stuartburch.com/1/post/2012/08/manet-money.html. (3) Stuart Burch, "Purloined for the nation", 03/04/12, http://www.stuartburch.com/1/post/2012/04/purloined-for-the-nation.html.  Andy Murray + Wimbledon + nationalism Could there possibly be a more depressing combination? I very much doubt it. Alas, the media’s obsession with all this old balls made it harder to avoid than Christmas. Fortunately on this occasion there is cause for genuine interest and, indeed, celebration. This is because the local foreigner’s loss was Oxfam’s gain. When a gentleman by the name of Nick Newlife died in 2009 he generously bequeathed his entire estate to the charity. This included a betting slip. Back in 2003, Newlife wagered £1,520 that the Swiss tennis player, Roger Federer would win Wimbledon seven times before the year 2019. At odds of 66/1, Oxfam will now collect Newlife’s winnings: a cool £101,840. So, just for once, can we please forget about new balls and old nationalisms? Let's sing the praises of Newlife instead.  Until recently I have lived my little life in only two dimensions. All that changed on Tuesday 3rd July. Because on that evening – and very much against my better instincts – a Siren persuaded me to pay a small fortune for a pair of cheap plastic spectacles. Despite resembling sunglasses these eyepieces afforded no protection against ultraviolet light. They were, however, effective at creating a spurious sense of depth when watching 3D movies at the cinema. The effect they produce is similar to that experienced when looking at Soviet realist portraits of Stalin. All too often Uncle Joe looks like an overlaid cut-out that could at any moment topple out of the frame. A reviled monster of a slightly different kind featured in the film that I settled down to watch. The creature in question had been brought back to life thanks to another siren song, this time broadcast across vast tracts of the cosmos. This call succeeded in luring a rag-bag band of unsuspecting space travellers into its slithery embrace for the purpose of injecting a little fire into their bellies. Hence the title of the film: Prometheus. Ridley Scott’s blockbuster revives and reprises a creature that was first introduced to movie-goers way back in 1979. This was Alien, one of the masterpieces of cinematic history. For its part, Prometheus must count as one of the disasterpieces of the silver screen – whether it be in two dimensions or three. Luckily for me, the saving grace of Prometheus was the fact that it happened to be the first (and I suspect last) time that I opted to pay for an extra dimension. Fittingly enough, this 3D experience turned it into an expensive novelty. Alien was visually stunning, excellently written and well acted with a plausible (albeit fantastic) plot that remains to this day thought provoking, gripping and genuinely scary. Moreover, it was underpinned by an excoriating social commentary on the machinations of big business. The omninational Weylan-Yutani corporation’s casual disregard for its human employees contrasted with the genuine interest and sympathy they generate in us, the audience. Prometheus is the absolute antithesis of all this. Its plot merits no comment whatsoever. And yet, bizarrely enough, the fact that it is so utterly awful renders it the perfect prequel to Alien. A specially-made pair of 3D spectacles should be hastily manufactured and given to Ridley Scott’s extraterrestrial creation. I have a feeling that its razor sharp mouth would hang open in gob-smacked admiration for its master’s work. This is because Prometheus is the ultimate parasite. It owes its existence entirely due to its host. Without that host – i.e. the original film – it would be nothing. Alien’s prequel is a mind-numbingly naked commercial venture that treats the paying public with the same contempt as the Weylan-Yutani company showed to the doomed crew of the spaceship, Nostromo. One member of that crew is the character, Kane – played so brilliantly by John Hurt. In a particularly memorable scene we see him in a prone position, his features occluded by the facehugging Alien. The best way to sum up Prometheus is to look upon Kane as an embodiment of the 1979 film as a whole. Thanks to the prequel it is now no longer possible to properly appreciate that movie. This is because, enfolding it in a deathly embrace and leeching it of all its vital signs, is its bastard spawn: Prometheus. The unearthly star of Alien would surely applaud this act of ruthless parasitism. But s/he would, I feel, have one criticism. The name is all wrong. The single word title beginning with “P” should not be Prometheus but Parasitoid: a parasite that kills its host. Because that’s exactly what Prometheus does to Alien. Images to celebrate James Joyce’s Ulyssess on “Bloomsday” – 16th June.

|

Para, jämsides med.

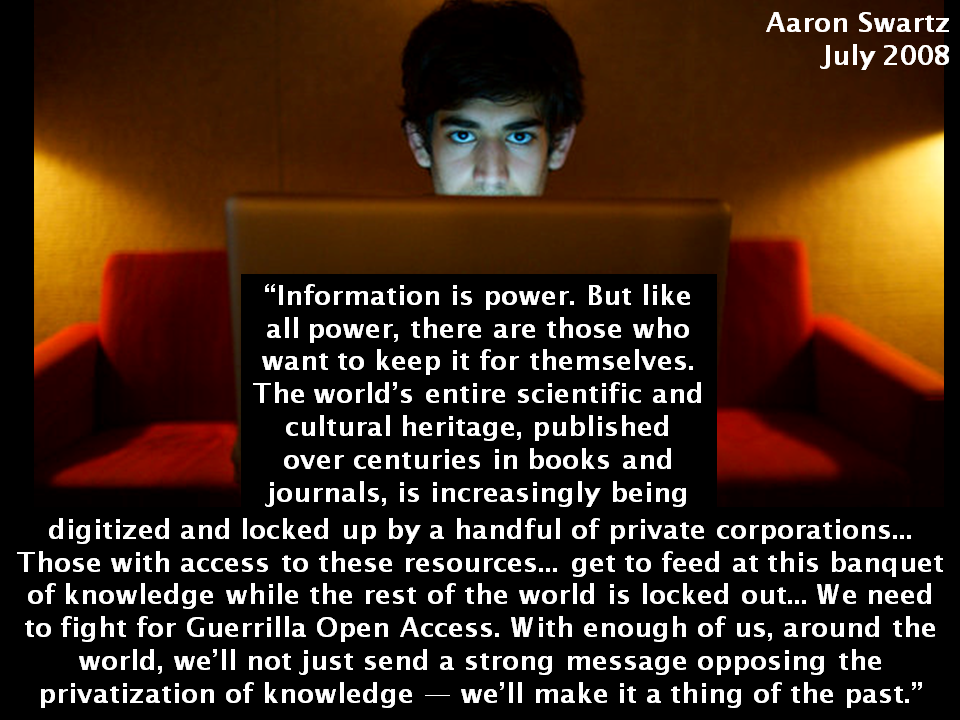

En annan sort. Dénis Lindbohm, Bevingaren, 1980: 90 Even a parasite like me should be permitted to feed at the banquet of knowledge

I once posted comments as Bevingaren at guardian.co.uk

Archives

July 2019

Categories

All

_

Note All parasitoids are parasites, but not all parasites are parasitoids Parasitoid "A parasite that always ultimately destroys its host" (Oxford English Dictionary) I live off you

And you live off me And the whole world Lives off everybody See we gotta be exploited By somebody, by somebody, by somebody X-Ray Spex <I live off you> Germ Free Adolescents 1978 From symbiosis

to parasitism is a short step. The word is now a virus. William Burroughs

<operation rewrite> |