My destination was a high temple of mammon in the bustling heart of the metropolis. The culmination of my pilgrimage was inside: it lay in silent, pristine isolation within a darkened room flanked by two acolytes.

This, alas, made it impossible to read the sacred text inscribed onto the reliquary. However, I knew what it said because the same prophesy had been reproduced in large letters on the wall of the antechamber: "... I felt a loud, unending scream piercing nature."

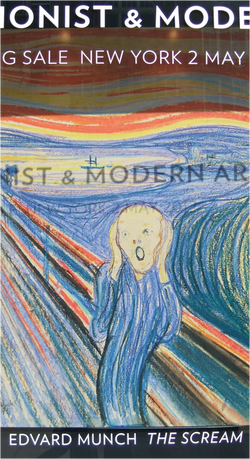

It was here that other canonical stories were told alongside portraits of the great creator and reproductions of other icons he had produced. The end wall of the anteroom was entirely taken up with a painted image of a prophetic sky. The flowing lines of red and yellow in the heavens found an echo in the procession of pilgrims waiting expectantly. The long, snaking queue they formed was surveilled by more attendants.

And then - oh joy of joys - I found myself before the one thing that I knew I could never possess. And yet - for the two minutes that I was able to be in its presence - it was mine. The jewel was dazzling in the darkness. The reds burned my eyes. But my troubled soul was eased.

For are we not told again and again that we live in the age of angst? Hell and damnation are just around the corner. The future is to be feared. We find temporary salvation in past perturbations: sunken ships being particularly popular just now.(1)

What better way to silence past pains and future fears than to stand before a silent scream of anguish?

And it was now or never: the relic might never be accessible to me again. This is because it stands at a liminal moment between private ownership and public auction. Perhaps its future owner will opt to be cremated with the relic in a last desperate attempt to disprove the adage that there are no pockets in a shroud?(2)

Surely no public institution could scrape together the requisite sum when it goes to auction in New York on 2nd May? Its financial value is boosted by the knowledge that, whilst there are other versions of the same relic, these all exist in public institutions and will thus never come on the market.

Indeed, it felt as if I had been singled out for special treatment. I stood and queued not once but twice to be in the presence of holiness. On my second visit I lingered longer than my fellow true believers and fell into conversation with one of the acolytes standing guard. I was rather shocked to discover that he was a normal person - a pilgrim like me. Soon the others left. I was alone with the security team and one other person. His accoutrements marked him out as a Very Special Person: around his neck were several cameras. Surely no-one normal could be allowed such equipment, especially of such phallic magnitude as the long lens he held in his skilful hands.

I too held something that, I think, helped ensure I was able to dwell a little longer than the others: a pen and notepad. Moreover, my closely cropped hair and rather ridiculous beard perhaps marked me out as someone who just might possibly be out-of-the-ordinary and important enough not to treat with the usual contempt reserved for "the public".

Be that as it may, I was able to witness a miracle. For lo and behold, the ceiling began to slide back and in shot radiant shafts of sunlight. What is more, one of the two glass screens standing between me and the relic was drawn aside. This, it transpired, was because The Camera Man worked for a hallowed organisation referred to cryptically as "The F.T." and he was here to take a photograph of the relic and its current owner!(3) The glass was therefore a hindrance - so too was the darkness.

So I watched in awe as blinding light flooded into the room. I had a sudden urge to gather together the security team and arrange them into a pose plastique of Caravaggio's Conversion of Saint Paul (after all, we all saw the light but heard not the voice).

Surely I could never dream of experiencing anything so wondrous?

I remained rooted to the spot. More acolytes came. They were evidently getting increasingly anxious because the owner was delayed doing something else. The crowds outside were lengthening. Something had to be done. So The Scream's screen was replaced and the natural light shut out once more. The room's interior slowly disappeared and the relic shone forth again.

Returned to the darkness, I began to castigate myself: Oh, ye of little faith! How could I have doubted my belief in Art? The vision had been there all the time. It was I who had wavered.

Soon the chamber was filled with other pilgrims and the two minute rule was enforced.

I was ejected and found myself amongst other artworks.

But I had been changed by my recent experiences. I began to look more critically at the second-rate relics that surrounded me. These were clearly of a lower order. They were rudely stacked together cheek by jowl. Is it not the case that, when one has been touched by greatest, mere brilliance leaves one disenchanted? This was exacerbated by the fact that I could come as close as I liked to these tawdry things with their million dollar price tags.

I sidled up to other images by the same disciple who had produced the relic before which I had just genuflected. One was described as being "Property from a European private collection". Yet four others, apparently of equal authenticity and appeal, were marked as "Property from an important private collection".(4)

How curious! Value is clearly not inherent in the relic itself; greatness is at least in part conferred on it by the significance of the anonymous owner.

Ownership of a different kind struck me when it came to another work, namely Bridle Path painted in 1939 by the American artist, Edward Hopper (1882-1967). This was described as follows:

"Property of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, sold to benefit acquisitions."

This got me thinking about the great relic next door. Maybe its cousins in public collections aren't quite as immune from sale as we might suppose? What goes for San Francisco Museum of Modern Art might, one day, apply to Norway's National Gallery or Munch Museum...

In an effort to repress this troubling thought, I started to ponder who was behind the present sale - and why? In search of answers I sneaked back to the antechamber and consulted the oracles on the walls. Its vendor is Petter Olsen, a businessman whose ship-owning father - Thomas Fredrik Olsen (1897-1969) - was a neighbour of the artist, Edvard Munch. Olsen junior skilfully deployed the same sort of logic as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: the work was being sold on the pretext of wishing to establish a new museum devoted to the artist.

The text neglected to mention one other interesting fact: the owner's older brother had been disinherited of the majority of the artworks that his father had acquired. This triggered a long and costly legal battle that was eventually won by Petter Olsen.(5) Had his brother Fred triumphed, would he have chosen to flog off his family inheritance like young Petter?

All this sibling rivalry sounds like a Nordic version of the story of Isaac and his twin sons Esau and Jacob. Oh, the religious parallels! And what better way to mask the fact that the saga described here is entirely about earthly power and riches than by dressing it up with pseudo-religious paraphernalia?

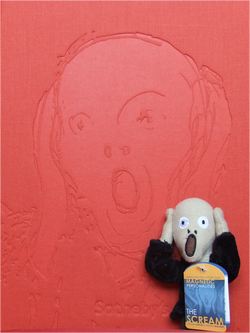

Knowing as I do that "even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters' table" (Matthew 15:27), I assembled a collection of mementos of my visit. These included the thickest, most luxurious napkin I have ever touched. Embossed on it are silver letters that spell the word: Sotheby's. I also retained an apparently free pen and a leaflet with thumbnail reproductions of the things I had seen. I even bought a special book, the cover of which is embossed with an image of the relic.(6)

I decided to make my way to another temple known as Forbidden Planet. I arrived to the plaintive cry of a young boy aged about six or seven. Oblivious to his father's attempts to placate him he wailed repeatedly: "I just want to buy something!"

This young lad had already learnt one of life's crucial lessons: we consumers are fated never to be satisfied because we know that there is always something better just beyond our reach. That's why Edvard Munch's The Scream is so important. It is at the apex of the consumer market. The ultimate commodity. Tastes will change but its values are - we are led to believe - eternal.

Pilgrims of the past used to acquire souvenirs to show that they had been on a pilgrimage. I have a reproduction of one such pilgrim badge depicting the early British Christian martyr, Saint Alban. He is shown in rude health despite having just being decapitated. The scene is all too much for the Roman soldier standing alongside: in his hands he holds his eyes, which have literally popped out of their sockets in disbelief.

I travelled to Forbidden Planet to acquire a little memento of my day. And I found the perfect thing: a plastic pigeon complete with plastic pooh.(7) A bargain at £44.99 ("How much?" cried my wife!) This foul fowl will decorate our new home, greeting unsuspecting visitors as they enter. These guests may very well think that they are looking at a pathetic plastic toy acquired by an immature weirdo. Yet they will in truth be in close proximity to pure genius: a plastic piece of the true cross. Just like my battered version of The Screaming Scream seen in the video above.

Because, I scream, you scream, we all scream for Edvard Munch's many, many, many Screams.(8)

___

Notes

(1) Two such ships currently being commemorated are RMS Titanic (sank 15th April 1912) and HMS Sheffield. The latter saw service during the Falklands War. It was attacked by an Argentine Lockheed P-2 Neptune aircraft on 4th May 1982 and sank six days later. Ten crewmen died - as I heard this morning in a very moving episode of BBC Radio 4's series, The Reunion (http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01dmdnb#synopsis).

(2) This is a reference to the Japanese businessman, Ryoei Saito. In 1990 he acquired Vincent van Gogh's Portrait of Dr. Gachet for the then record-breaking sum of $82.5m. Rumours have since circulated that he issued instructions for it to be cremated with him when he died in 1996. Its location remains uncertain.

(3) The photographer in question appears to have been Charlie Bibby. His highly amusing image was used to illustrate the following article, Peter Aspden, "So, what does The Scream mean?", Financial Times, 21/04/2012, accessed 22/04/2012 at, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/42414792-8968-11e1-85af-00144feab49a.html.

(4) These are, respectively, Edvard Munch's Summer Night (1917, see Woll, Vol. 3, No. 1235); Woman Looking in the Mirror (1892, see Woll, Vol. 1, No. 270); Clothes on a Line in Åsgårdstrand (1902, see Woll, Vol. 2, No. 529); Night in Saint-Cloud (n.d., see Woll, Vol. 3, No. 287); and The Sower (1913, see Woll, Vol. 3, No. 1043). See Gerd Woll's four-volume catalogue raisonné, Edvard Munch: Complete Paintings (London: Thames & Hudson, 2009).

(5) Gro Rognmo, "Lillebror Olsen tok siste stikk", Dagbladet, 06/06/2011, accessed 20/04/2012 at, http://www.dagbladet.no/nyheter/2001/06/06/261987.html.

(6) Sue Prideaux, Reinhold Heller, Adam Gopnik & Philip Hook, Edvard Munch: The Scream (New York: Sotheby's, 2012).

(7) This is a Kidrobot Staple Pigeon. See http://stapledesign.com/2011/11/kidrobot-staple-pigeon.

(8) The famous phrase "I scream, you scream, we all scream for ice cream" is from the brilliant film Down by Law directed by Jim Jarmusch (1986):